Before Isis released the video showing al-Kasasbeh’s burning, the Jordanian authorities had started negotiations with the terrorist organization, appointing for that role the preacher Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, who was close to al-Qaeda, and was very influential in Salafi-Jihadist circles, especially the movement’s Gulf branches, and particularly Saudi Arabia.

Throughout the negotiations― initiated by al-Maqdisi while he was still in prison― the Jordanians demonstrated flexibility and were willing to exchange al-Kasasbeh with several Isis prisoners, including Sajida al-Rishawi who plotted to bomb an Amman hotel.

When al-Maqdisi saw the footage of al-Kasasbeh’s death, while negotiations were ongoing, he was taken by surprise.

The Jordanian response to Isis’s failure to keep its end of the bargain, was the execution of Ms. al-Rishawi, along with other Isis prisoners.

Weeks after the incident, al-Maqdisi was released.

When we sat with him, he emphasized that decision-making in the “Caliphate State” is in the hands of former Iraqi officers, and Isis is more a Ba’athist organization than a salafi-jihadist group.

“They lied to me,” al-Maqdisi told us, “and they lied to Isis’s religious legislative members who had vowed not to kill the pilot.”

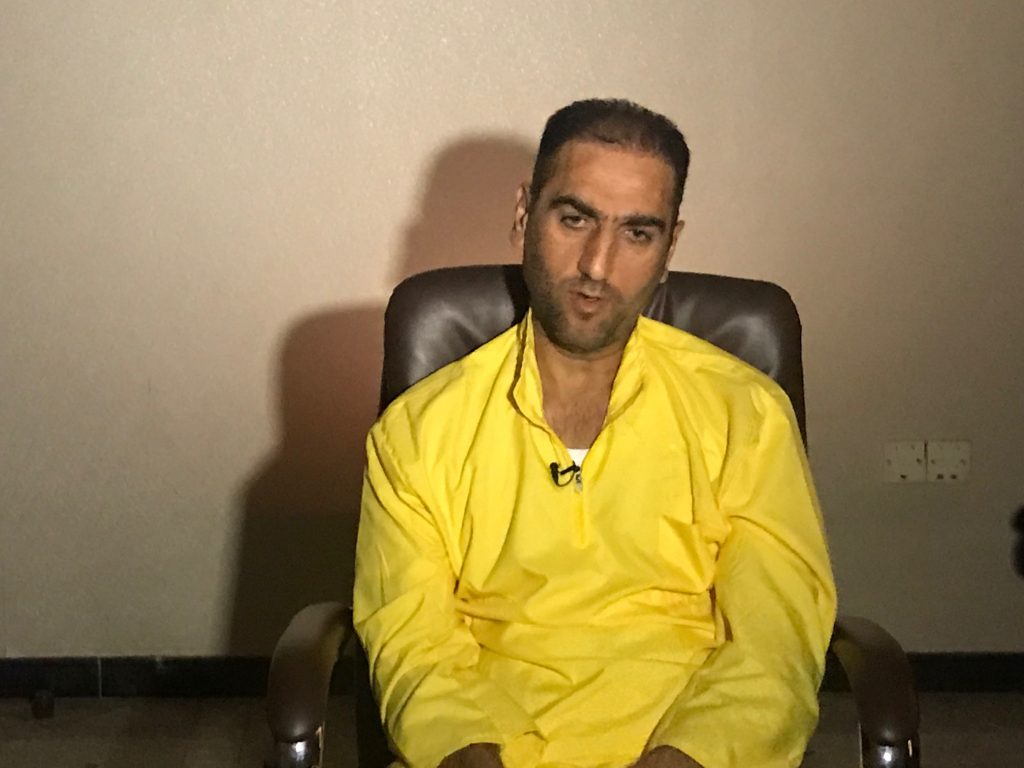

“Daraj” met with Ismail Alwan al-Ithawi, director of Isis’s Education Bureau, at his detention center in Baghdad, where he was awaiting his execution.

Al-Ithawi noted that releasing the tape had an impact on Isis’s religious legislative body, highlighting that it was Turki al-Binali, the head of the Judicial and Legal Authorities Office (later killed in eastern Syria,) who represented Isis at the negotiations that were initiated by al-Maqdisi.

Al-Ithawi said that al-Binali personally told him that the Islamic State had not fulfilled its obligations.

Al-Binali was one of al-Maqdisi’s pupils and published articles on the preacher’s website, “The platform of Unity and Jihad.” So when the Islamic State aired al-Kasasbeh’s videotape, al-Binali and most of the group’s Islamic religious legislative leaders were furious.

Apart from Isis’s failure to keep its promise not to kill the pilot, those leaders condemned his burning alive, which is anathema to the Islamic dictum: “No one may punish by fire other than the Lord of Fire.”

However, Al Ithawi—in response to a question posed by “Daraj” about the Islamic State’s justification for the use of the burning method— said: “The Islamic State didn’t bother to justify its actions. Complaints were no more than mere useless protests, after which everyone kept his mouth shut.”

It seems that what al-Maqdisi said— regarding that decisions in Isis were in the hands of the former Iraqi Armed Forces officers, and that the State’s religious legislative leaders were the weakest link— can easily be substantiated.

According to al-Ithawi, burning al-Kasabseh created confusion and controversy in legislative circles without, however, exceeding protest levels.

The Islamic State, who had invested in those officers and the Ba’athist fatwas (religious rulings) in Iraq and Syria, gave them the opportunity to double down on the violence and the accompanying gruesome material, which they employed to further terrorize their subjects.

Al-Kasabseh’s family, for its part, has accused Saddam al-Jamal, an Isis Syrian leader, of executing their son’s killing. The Iraqi Intelligence Service had succeeded in capturing al-Jamal in a security operation inside Syrian territory. He was then tried and sentenced to death in Iraq. Today, the family is requesting his extradition to Jordan.

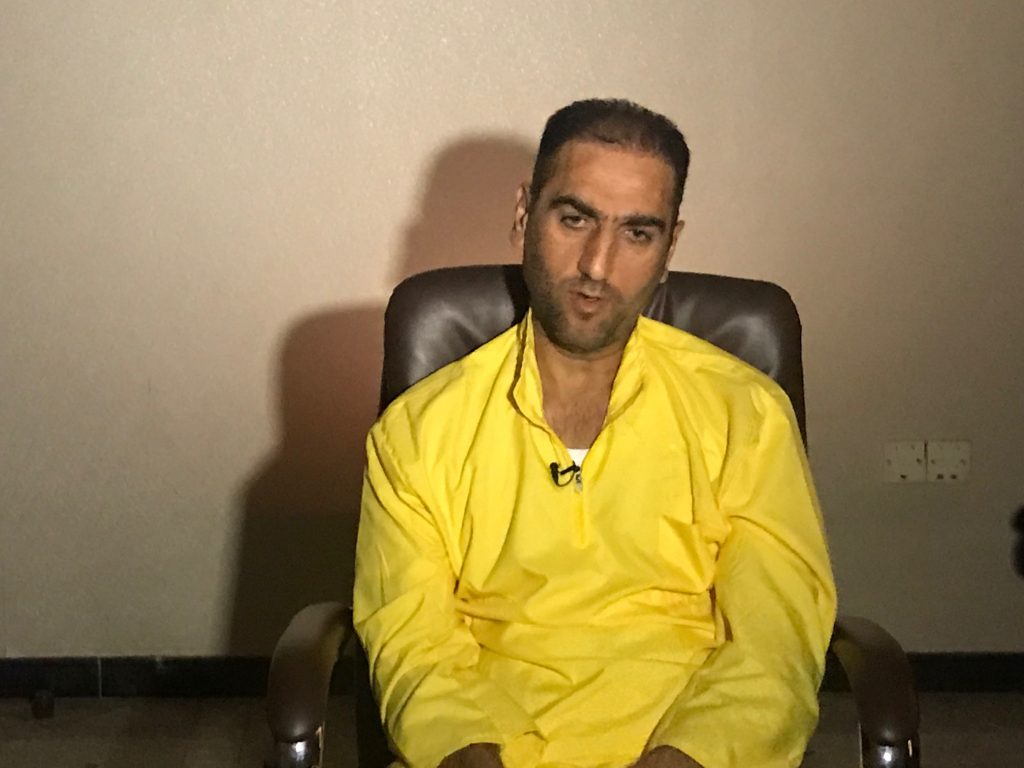

“Daraj” met Saddam al-Jamal at his detention center in Baghdad, where he denied his involvement in al-Kasasbeh’s death, despite the fact that the area where the plane was shot was under his command.

Al-Jamal― who is infamous for his murderous past and beheading videos– also denied committing deeds that were documented and filmed, which cast doubt on the credibility of his denial in al-Kasasbeh’s case.

Stories of Saddam al-Jamal’s murder of a thousand Syrians with his bare hands, and his participation in the Deir ez-Zor’s countryside massacre of al-Shaitat clan, are public knowledge.

Yet, he denied it all, claiming he was in Raqqa when the massacre occurred, and that he was not the one who severed the heads he was photographed holding up.

In one of those photographs, al-Jamal brandished a severed head in order to vex al-Nusra Front who had killed his brother.

Even though there is no hard evidence that al-Jamal participated in al-Kasasbeh’s burning, many indicators point to that likelihood. Al-jamal had committed even more heinous crimes than al-Kasasbeh’s killing.

Iraqi investigators’s inclination to deny the information provided by al-Kasasbeh clan, referring to al-Jamal’s involvement in the burning operation, is shown in Iraqis’ desire to execute him in Iraq instead of extraditing him to Jordan.

Despite the fact that, as al-Ithawi says, Turki al-Binali was one of the closest people to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, that did nothing to compel Isis to keep its end of the bargain in the prisoners exchange negotiations.

As for Saddam al-Jamal, he came into Isis from as an outsider to the Salafi-Jihadist realm. He was a military commander in the Free Syrian Army before joining Isis in 2014.

He was a member of the violent Ba’athist apparatus in the Islamic State. Although his biography does not suggest his affiliation with the Ba’ath, the man was born in al-Bukamal, on the border separating the two Ba’athist states, and his name echoes the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party in Iraq, while his service in the Syrian Armed Forces is redolent of the Syrian Ba’ath. Al-Jamal escaped the Free Syrian Army after its defeat by al-Nusra, just like Iraqi officers escaped the disbanded Iraqi Army and joined the Islamic State.

In terms of violence, Isis has always made the impossible possible.

One meets Saddam al-Jamal and, beyond the man’s own narration of events, senses that all the stories one had read about him are still written all over his face, despite him being one step away from his execution.