From the moment the State of Greater Lebanon was founded one hundred years ago to the recent Bkerke initiative to call for a UN conference to save Lebanon, as well as neutrality from any external conflicts, internationalization has never been absent from the Lebanese political discourse.

If we look at the past, it becomes clear that today’s initiative is part of the Maronite patriarchy’s traditional “work kit” used in the fifties and seventies of the last century.

The problem is not the intervention itself, but rather the nature of the intervention. The traditional political components only master a single form of internationalization, centered in form and substance on the concept of welfare protectionism, meaning: privileges and guarantees are given to local groups, through which internal power sharing is reconfigured.

external protection was the main guarantee for internal stability.

Internationalization as a Governing Tool

Internationalization has been a feature of the Lebanese reality since its inception. And loyalty to external forces is a common thread between all those who ruled Lebanon. Parties differ, reposition and change views, yet the essence remains the same. The Lebanese formula is unable to secure a state of internal political stability otherwise.

The idea of heading to an international conference precedes the 1920 foundation of the State of Greater Lebanon. The idea arguably dates back to the 1860 sectarian war and the establishment of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate [a semi-autonomous subdivision of the Ottoman Empire).

In those days, external protection was the main guarantee for internal stability. Under such protection, internal stability was established in exchange for external influence.

The idea further evolved following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire when various delegations were formed to attend the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and discuss the Lebanese cause. External protectionism of local groups was institutionalized during the French mandate for Lebanon. It continued in the post-independence period with several political and military foreign interventions: from the expulsion of the French to the 1958 uprising, and from the 1969 Cairo Agreement to the 1989 Taif Accord, which sealed the Maronites’ political defeat. As sponsors changed, the phenomenon continued until the 2008 Doha Agreement, which consecrated Hezbollah’s victory following a week of Beirut clashes earlier that year. In short, each time a local group was presiding over a system of shared power, it had an external benefactor.

Hezbollah as an advanced model of internationalization

Hezbollah presents an advanced model of internationalization in Lebanese politics. On the one hand, it was established by a “revolutionary” decision to offer geopolitical momentum to the emerging Islamic leadership in Tehran, amidst its war with Iraq, and its need for a bridgehead connecting it to Palestine. On the other hand, its establishment met the need for Shiite leaders to present a political model different from the Lebanese National Movement and the cultural and political configurations under the mantle of the late Imam Musa al-Sadr.

Thus, even before its establishment, Hezbollah had been a form of internationalization on the Lebanese political scene. Over the past four decades, however, it came to represent an advanced form of it. Hezbollah broke with the traditional protectionist pattern of internationalization, which the Maronite Patriarchate and political leadership traditionally sought in its relationship with western countries.

The model followed the idea of an Arabist, external link to political Sunnism, the main features of which first crystallized in the 1950s, intensified after the Taif Agreement, continued until the 2005 assassination of Lebanon’s former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and was buried with his son Saad Hariri’s stints as Prime Minister.

Read Also:

In this context, Hezbollah’s relationship with the Iranian system of government as an organizational and procedural extension is an advanced model of the Lebanese internationalization formulas. The party does not want Lebanon to be an innate entity that lives on the margins of Iranian influence, nor does it want it to become integrated in the depths of Arabism.

It wants Lebanon to be in its image and likeness, an organic part of the “archipelago” of the imperial Wilayat al-Faqih system and its international connections linking Caracas to Qardaha.

Thus, it sought to transform Lebanon, turning it into something like Iran’s 32nd province (Ostan), which is administered by a somehow independent government. Hezbollah has always viewed itself a protector of the vulnerable, resisting “external colonialism,” which it geographically defines as the colonial West.

But by monopolizing the representation of the “vulnerable in the East,” and being part of the Revolutionary Guard setup of the Islamic Republic, the party has become a central node in the operation room at the frontlines of Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Lebanon.

Hezbollah today is not in the same position as the Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon was in relation to the Sublime Porte in Constantinople, nor is it as an integrated component of the United Arab Republic of Gamal Abdel Nasser or even a subject of the Saudi monarchy during the political “haririya” stage.

Hezbollah was established as an organic extension of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard to play a structural role comparable to that of the former East German intelligence service, known as Stasi, or the Vichy government in France in the days of Nazi Germany.

One of the most contradictory positions taken in discussions by official and unofficial representatives of the party on social media, is accusing others, who disagree, of internationalization and having links with foreign countries.

Yet, meanwhile they whisper about the possibility that Hezbollah Secretary General Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah may be among the names nominated to succeed the Wali al-Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist). Not to mention the rumor that Nasrallah refused to succeed Qassem Soleimani to assume leading the Quds Force.

This comes on top of Nasrallah’s absolute allegiance to the Wali al-Faqih, a name often loudly chanted by the party’s supporters to intimidate opponents, especially at universities.

Saving Lebanon to Save Itself?

Bkerke returns to the fore by calling for an international conference to save Lebanon and neutrality from any external conflict. Maronite Patriarch Bechara Al-Rai adopted the full notion of the civil state and talked about the importance of citizenship outside one’s sectarian identity.

The initiative is an attempt by Bkerke to save itself and to save the Lebanese system, which still reflects part of an entity created by former patriarchs, and which in reality means preventing the Hezbollah-led collapse of the ruling system.

The position of the patriarch supporting central bank governor Riyadh Salameh, who oversaw the plundering of Lebanese bank accounts, the widespread corruption, the failure to provide any form of protection against economic collapse, as well as the cover offered for Christian political leaders: all these factors make the initiative more a necessity for Bkerke, than for Lebanon.

As Bkerke does not possess the executive tools needed to achieve its goal, it must rely on the old “work kit,” which may be a weakness. Yet, as long as it continues, it may have achieved one major goal by withdrawing the “strong Christian ally” card from Hezbollah’s hands.

Seeing Hezbollah’s haste to avoid a direct confrontation, we can only try to foresee its position among the many variables in the current political climate.

Today, we are not awaiting another bishops statement, nor are we facing the establishment of a new Kornet Chehwan meeting, and we are certainly not back at May 7, 2005, the day current President Michel Aoun returned to Lebanon.

With its call for internationalization, Bkerke has placed Hezbollah in a position of direct rivalry, or at least disagreement, with the largest Christian sect in the Middle East.

Meanwhile, the head of the Catholic Church worldwide was visiting Iraq, meeting the main religious authority in Najaf and Karbala, which disagrees with the allegiance system of the Islamic Republic and its political orientations in and outside Iraq.

This inevitably deprives the party of playing the role of “protector of minorities” in the east.

Hezbollah built part of the legitimacy regarding its intervention in the Syrian War on that. And, through that role, the party theorized the role of Qassem Soleimani as redeemer of diversity in Iraq.

Hezbollah’s problem with the Bkerke initiative lies not in raising the slogan of internationalization itself, nor in the content of the Patriarch’s speech calling for a neutral Lebanon, but rather in the fact that the initiative returned the party, and the regional axis it represents, to its primary affiliation, as part of a political Islam unable to build bridges and agreements with other components in the east.

The danger of the patriarchal plea is that it may contribute to overthrowing the theory of alliance of minorities that Tehran theorized. A theory for which Qassem Soleimani did everything in his power to consolidate it as the main social and political framework for normalizing Iranian influence in the region.

In doing so, Soleimani adopted a methodology very similar to the one he used for developing Iranian influence among the Afghan tribes. Damascus rode its wave, Baabda lived on it, and Russia sponsored it.

October 17

October 17, 2019, came to express a qualitative shift in the reformist discourse and departure from the traditional institutions of the post-Taif republic.

It paved the way for a process of political amputation from the sectarian power systems. From the start, it was in contradiction with the entire authoritarian system. The “revolutionary spirit” was in the face of any possible juncture with the parties in power and the sectarian institutions behind them.

This also applies to Bkerke, which until recently provided the only oxygen left for the “leadership” of Gebran Bassil.

However, the noncompliance in the position towards the institutions of the ruling system did not extend entirely to the political discourse. The revolutionary groups practiced a form of self-censorship for various reasons, most notably regarding their position on Hezbollah.

Initially, the bet was to set aside the party and its Secretary General to avoid “unjustified” hostility towards the Shiite public – an attempt that proved unsuccessful and showed insufficient understanding of the party’s role.

The bet was for the party to take a stand in support of change. Instead, it responded with treason, and talked about “embassy agents.”

The rhetoric then expanded to include the political role of the party, yet without mentioning the Secretary General. The answer that followed were the brutal beatings of Nabatiyeh and Kfarroman, burning tents in Tyre, and “thugging” on the Beirut Ring and Martyrs Square.

Thus, Hezbollah, and its national and regional positioning, has become something of an elephant in the political decision-making room of most revolutionary groups. The intimidation from the party against individuals and groups in Beirut and in the south, and the echo of the assassinations carried out by fellow axis members against demonstrators in Baghdad, sufficed to determine the margins of what is deemed acceptable discourse.

In return, the groups, or at least some of them, fell into the trap of presenting defenses to prove their “patriotism.” This was the moment when Hezbollah succeeded in killing the October 17 uprising, domesticating it, and transforming it into something like the National Coordination Body for the Opposition Forces of National Democratic Change, which was the internal opposition to the Assad regime at the start of the Syrian revolution.

The only difference is that the party was not able to find another Hassan Abdul-Azim …

The Beirut blast revealed, beyond doubt, an organic link between the various components of the ruling system in Lebanon.

August 4

Since October 17, the different parties within the ruling system have been supporting and reinforcing one another under the supervision of Hezbollah’s Secretary General. Following the Beirut Port explosion on August 4, the ruling components further united, perceiving the blast as “destiny and fate,” as said then Minister of Health, and Hezbollah representative, Hamad Hassan.

They thus adopted the same mentality that ruled the first days following the assassination of Rafik Hariri, when the government cleared the bombing site after three days of mourning. The road was cleaned and paved to go back to “normal life,” as stated former Interior Minister Suleiman Franjieh. As if nothing had ever happened …

The Beirut blast revealed, beyond doubt, an organic link between the various components of the ruling system in Lebanon. The mutual protection between the corrupt and the militias showed that the political confrontation on the ground should not remain captive of the political margins determined by Hezbollah Secretary General’s periodic speeches.

These speeches became more frequent following October 17. They often aim to determine what is deemed permissible within in the Lebanese republic.

Journalistic investigations into the explosion showed a clear alliance between the system of corruption, political protection and illegal weapons. The alliance provides protection for the killer, the corruption, and the ones who converted the Beirut port into a ticking semi-nuclear timebomb.

The repercussions of the blast also indicate that internal political action remains deficient if not accompanied by a strategy aimed at influencing international public opinion.

In fact, the French initiative and other international efforts were absorbed and digested internally in order to maintain the balance of power. That is why internationalization has become a complementary need for the struggle within Lebanon.

However, the challenge remains the nature of the desired internationalization, its tools and methodologies. It must protect national sovereignty and enable the struggle inside Lebanon, without reproducing neither the welfare protectionism of international conferences nor the organic affiliation with an imperial system.

What to do?

This remains the first question that must be addressed in determining the features of a foreign organizational and political dynamic. Here, the task of liberation from, first, the intellectual intimidation practiced by Hezbollah and the ruling system, is a priority on the road towards building action strategies to influence international public opinion and decision-making centers.

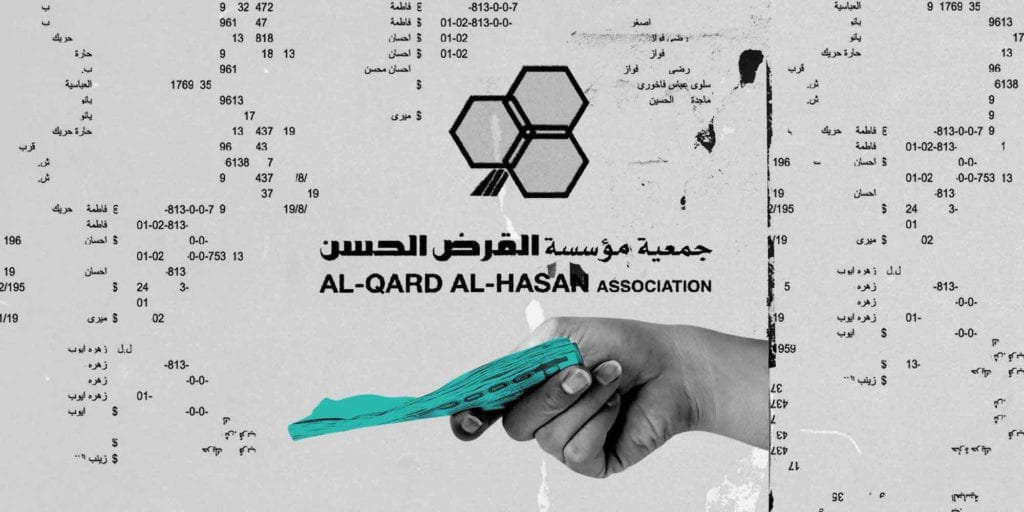

Internationalization is a righteous demand for a righteous cause. Those who plundered the depositors’ money in the banks and bankrupted the country will not be held accountable without turning to the international financial system to prosecute the looters and hold them accountable, freeze their wealth and recover people’s money.

How can the judiciary from a rogue authority like Lebanon’s be trusted to transparently investigate and hold the culprits accountable? Within Lebanon it is virtually impossible to uncover the truth and bring justice without turning to the international justice system.

The second question is: how? Is it possible to form a Lebanese lobby, not sectarian, nor confessional? A lobby that coordinates its work between the European Union, North America, international organizations and China, with the aim of linking aid to certain specified targets?

The latter should start by adopting laws and working towards an independent judiciary under international supervision. The judiciary must be the first step towards achieving justice for the Lebanese. Justice for the killers! Justice for the thieves! Justice for the aggressors! Justice for the patriarchal system! Justice for every human being in Lebanon!

The Lebanese cannot continue to live in a system that punishes the victims and honors the murderers. Justice is what people need most. Lebanon today is under occupation, and its liberation needs to be addressed.

Read Also: