In the 1920’s, it was Muslims in Lebanon who advocated federalism. More recently, it’s been the turn of mostly Christians or Druze to be federalism’s standard-bearers. Aside from their legitimate feeling of insecurity, shared by most Lebanese, the proponents of federalism have built a strong belief that their political project is the panacea for Lebanon’s ills. Their concerns are genuine, and I would not doubt their love of country. I would have had no inclination to challenge their convictions were it not for the unintended consequences of some of their claims. Repeating a proposition often enough does not make it self-evident without evidence. If federalism is a solution in the minds of some, it need not be tested at the expense of the Constitution.

Before discussing what’s implied by federalism in its current Lebanese version, let me start with what I cannot dispute. For Lebanese localities, or cazas, to have greater power in controlling their resources, accessing fiscal revenues, and striving for their economic and cultural welfare is a very desirable public policy. This, in fact, is part of the Taef Accord (part 1, section 3) which proposes the adoption of “expanded administrative decentralization” at the level of the cazas (or smaller districts), including the election of local representative assemblies to run the localities. To that aim, a devolution of power from central to regional authorities becomes a prerequisite (for example, the cazas of Besharri and Zghorta will each have its own assembly).

Likewise, more generally, one cannot but appreciate the different models of governance offered by federal states such as Switzerland, Germany, or the United States, and the dynamics that ties regional and federal authorities in the execution of public policy. All three models, however, were the results of a quest for centralization born out of a war effort. In the case of the Swiss Confederation, started informally in the latter part of the thirteenth century between independent cantons, it developed into a formal alliance in successive wars against Habsburg hegemony. The independent German principalities, consolidated in the seventeenth century under the successive Prussian kings and their formidable war machines, completed their unification in the nineteenth century under Bismarck’s astute war diplomacy.

The thirteen American colonies came together in the American Revolutionary War in 1775 against Great Britain over their objection to tax policies without colonial representation. American federalism, however, did not take its centralized form with the supremacy of the US Congress until after the Civil War in 1865 and the remaking of the US Constitution with the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments, which abolished slavery, defined citizenship, guaranteed the equal protection of the laws and the right to vote for African American citizens. Most importantly, the new Constitution gave Congress the power to enforce these amendments on the recalcitrant Southern states.

So if federalism has resulted historically from an effort toward centralization, how does it satisfy the aim of our Lebanese Federalists who wish to break away from a presumably centralized state? They resort to a more recent example, Brexit, or, better yet, the quest for Scottish independence. Along the way, they ignore that these were autonomous states, to begin with, and forego the enormous economic costs of such decisions (the cost of Brexit for the UK has exceeded to date $250 billion, and the economic cost for Scotland, with a population of 5.5 million, if it breaks away, is about $20 billion annually).

In order to understand the motivation behind recent “Lebanese Federalism”, let’s hear the arguments made by some of its advocates as in this recent post: “The Christian community considers that the Taef Accord stripped it of many of its rights… The Sunni group is going through a period of frustration… As for the Shiite community, it has been vocal, since the Taef Accord, about the Constitution excluding it from executive authority…and has ended up imposing its influence by force.” The post goes on to assert that the Taef Constitution of 1990 “is becoming a source of obstruction and instability.”

Reading these grievances, one concludes that the Constitution defines the rights and obligations of each community and has been an utter failure given the outcome. In reality, none of it is true, as the Constitution makes no reference to religion or communities. It guarantees equality before the law for all Lebanese (Article 22), and abides by the Universal Charter of Human Rights of which Lebanon is a signatory. The only exception is Article 95 which refers to an equal split in parliamentary seats between Christians and Muslims (and that as a transitional measure).

So with a claim based on a false premise, here’s the post’s conclusion: “Approach the issue of federalism with an open mind… Federalism is a way to avoid countries falling apart.” And as Lebanon is falling apart, federalism must be its way out.

Read Also:

But a federalism of what exactly? The above advocate isn’t referring to (autonomous) geographic entities. The grievances he cited are those of religious communities. With few exceptions, however, geography and religion in Lebanon are not the same because of the religious mix across the country.

To add some color, here’s another example of legitimate resentment presented by an attorney, Nadim Boustani, in a TV interview, only to turn it into communitarian advocacy. Boustani exhorts the public prosecutor to take legal action against Hizballah’s Al-Qard Al-Hassan Association, which takes cash deposits, provides loans, and requires of its borrowers gold deposits as collateral (pawn brokerage). Evidently, it’s a financial activity that requires a central bank license the Association does not have, while it expands its “business” across the country. Boustani goes on to conclude, rightly, that this is an unlawful activity akin to money laundering. What’s his recommendation to combat such illicit activity? Federalism, of course, to protect one religious community from the undue influence of another! How he justifies communitarianism as the solution to unlawful acts is not clear, and if his aim is to distance his community from the “Hizballah State”, why federate with it?

What’s being advocated in reality is a “federalism of sects”, a throwback to the earlier Ottoman millet system. Under Ottoman rule, from the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the early twentieth century, there was no notion of “citizenship”, per se, but a recognition of “subjects” of the Empire according to their religion, or millet. Muslims (Hanafi school of Sunni Islam) were first class, with the administrative and military privileges associated with such a status, and the rest (Orthodox or ‘Roum’, Armenians, and Jews) were relegated to a separate and inferior status. The identification of “nation” and “millet” could possibly apply in certain areas (Serbia or Bulgaria), but not in others such as Kosovo, or the Levant, including Lebanon, given the latter’s multi-religious makeup.

Generally, a system based on exclusion or differentiation lacks the social cohesiveness to create an efficient economy. With religious segregation and weak centralization, combined with dubious property rights, especially landed property, the Ottoman Empire was unable to cope with the requirements of economic innovation and progress, leading to its early decline in the second half of the seventeenth century.

By advocating a small-scale version of the-tried-and-failed Ottoman millet system, our Lebanese Federalists unwittingly regress away from citizenship and equality under the law, which are the prerequisites for a stable social order necessary for economic success. Let’s take the argument one step further. Suppose we created a single-denomination canton by merging the two aforementioned cazas of Zghorta and Besharri. Aside from the canton’s tenuous geographic position, what would guarantee its stability if reached by Hizballah’s tentacles with financial and military backing from Iran?

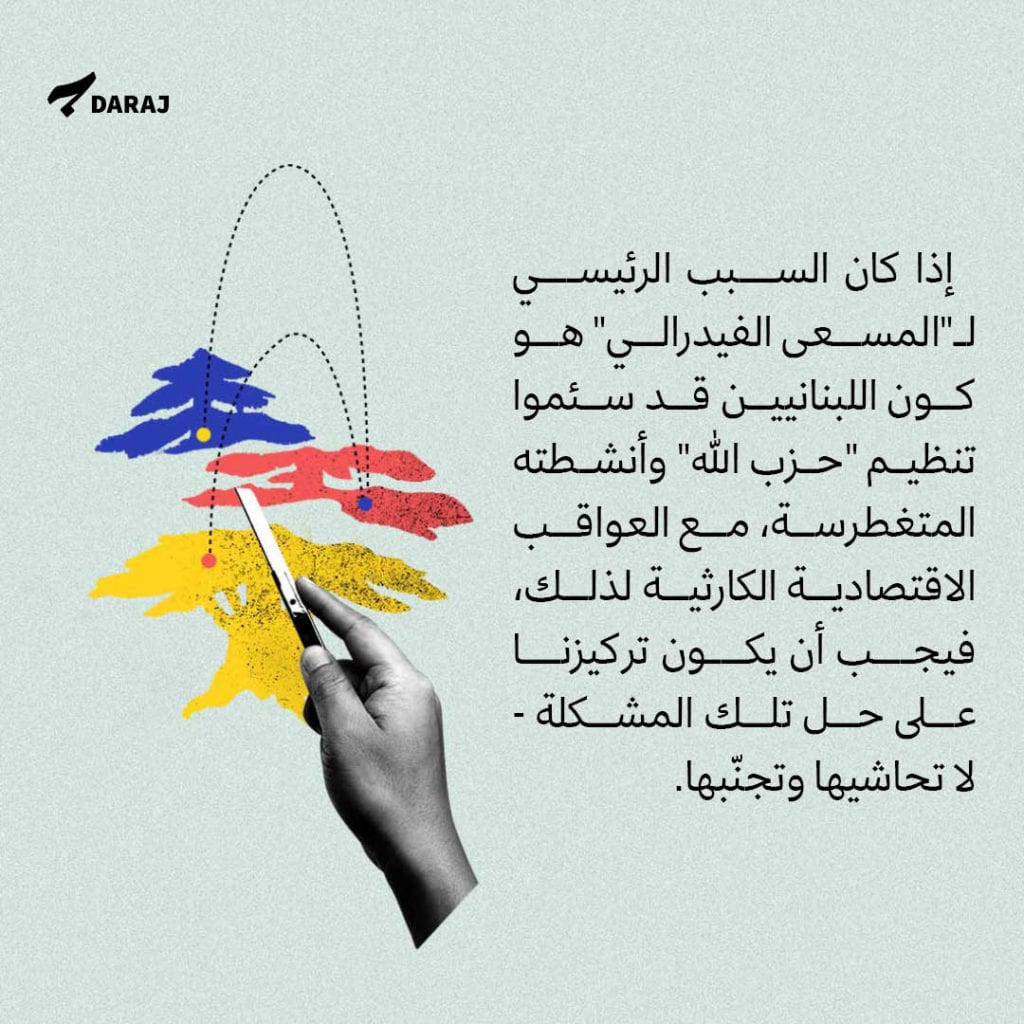

If the primary cause for the “federalist quest” is that Lebanese are fed up with Hizballah and its overbearing activity, outside the law, with its disastrous economic consequences, then our focus ought to be on solving that problem, instead of dodging it, in both its domestic and foreign dimensions.

Aiming for a half-baked “federalism” along confessional lines ignores the central question of lawlessness (which would permeate cantonal barriers if they were to exist) and leads to further political fragmentation and lack of economic viability. Dropping our secular Constitution by the wayside to quell communal frustrations makes no sense. The discriminatory practice since 1943 – at odds with the Constitution – of reserving the three main posts of government to three communities while excluding all others is where reform should start.

With the Taef Accord and its amendments of the 1926 Constitution (the First Republic), the executive powers of government were transferred from the President of the Republic to the Council of Ministers. Since Taef, the Presidency has had constitutional oversight rather than actual executive power (notwithstanding current obstructionism). It should no longer be the post coveted for its strong executive prerogatives if one followed the Constitution. It is in the Cabinet and in Parliament that political and economic decisions are made. Ironically, by devolving powers to the Cabinet and to Parliament, Taef has made it easier to move to a more flexible system of power sharing among the communities to the exclusion of no one.

x

Read Also:

No posts