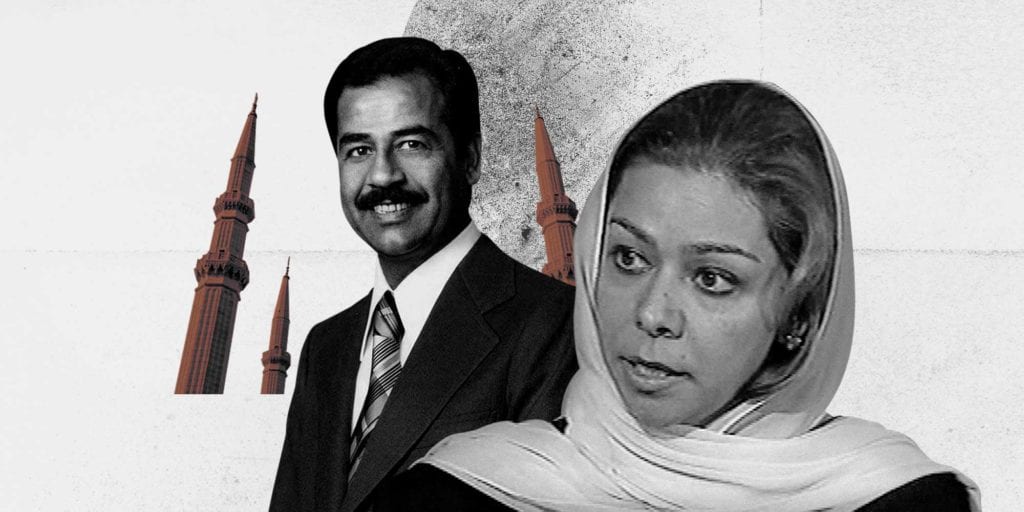

Safaa Ghali

Ahmed Abdel Samad

On January 10, 2020, around 7 PM, two unidentified assailants on a motorcycle aimed their weapons at the head and chest of 37-year-old journalist Ahmed Abdul Samad, killing him on the spot. His colleague, 26-year-old photographer Safaa Ghali, took three bullets to the chest and was taken to the Basra General Hospital. He lost his life one hour later.

The two well-known journalists were driving a car near the Assyrian Club in the center of Basra. They had just covered a demonstration, in which thousands of people protested against government policy, corruption and the proliferation of militias.

Abdul Samad (37) had years of experience covering hot events and sensitive files, including corruption and the growing role of militias regarding the economy and security of Iraq’s third largest city. He had also received a torrent of warnings and threats following his coverage of protesters being killed and his criticism on the growing influence of armed groups in Basra. Yet, he refused to stop what he called his “mission in life.”

His mission in life saw it ended at the hands of one of Basra’s “death squads,” which was led by a man in his thirties, who over the years carried out a series of assassinations and owns a string of investments in the heart of Basra. However, the security services know him as a mere criminal, while government data do not acknowledge his affiliation with the death squad.

It seems his gang was able to move freely under cover of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and other armed groups. Prominent members were able to take shelter in Basra and flee, with the security agencies being unable to stop them out of fear for an internal war.

According to Iraqi intelligence sources, many of them eventually ended up in Jurf al-Sakhar, a town some 50 kilometers south of Bagdad where the state no longer exists and militias rule instead.

Last Hours

“We were with a group of demonstrators in front of the Basra police headquarters,” said young activist Ali al-Nouri. “We had organized a sit-in demanding the release of our fellow activists who had been taken there. Abdul Samad was filming the event, while Safaa Ghali took pictures.”

Covering the sit-in was the last thing Abdul Samad and his colleague did before leaving the square. When news of the assassination reached the sit-in, which is at a distance of about 20 minutes on foot, Ali and the protesters marched there.

Al-Nouri had noticed something suspicious: a white Nevara pickup truck. The car’s tinted rear window prevented al-Nouri from seeing well. He only saw two bearded men sitting in the back. “The license plate number was not familiar,” he said. “It did not belong to Basra governorate or even Baghdad. It belonged to the Kurdistan Region.”

Following the sit-in and assassination Al-Nouri was forced to flee Basra due to the threats he and other demonstrators received. Armed groups accuse him of treason.

“Simply revealing names is of no value, unless the parties to which they belong are announced, as these are not personal crimes. Unfortunately, all indications show the case will be closed as soon as it is internally and externally settled. They want the killers to continue to move freely.”

A History of the Threat

Abdul Samad was known throughout Iraq for expressing his sharp opinions, supporting protesters’ demands and criticizing the authorities and parties in power. He had been threatened many times. He once told me about a call from an unknown number when he was working for the NRT channel. “I’m afraid my mother and family to know about this threat,” he said.

Since the 2015 protests, Abdul Samad had been in the crosshairs of the armed parties due to his criticism. During the 2018 Basra protests, which saw an increase in the targeting and assassinating activists, Abdul Samad became even more vocal, despite the enhanced risks due to his work for the Tigris channel, which the militias accused of supporting the demonstrations.

When there were no protests to cover Abdul Samad, among other things, focused on public and private corruption in Basra port. Journalist Montazer Al-Bakhit was one of Abdul Samad’s friends. We met him outside Basra. He is in exile, due the sharp deterioration in freedom of expression in his home governorate.

“During the 2015 demonstrations I received threats,” he said. “A lawsuit was filed against me by the ‘shock troops’ that cause incitement, which forced me to flee outside Iraq until the case was finally dismissed in court.”

But Al-Bakhit’s story did not end there. Even when the charges against him were dismissed, he could not return to his hometown. “I received a call from a reliable source warning me not to return to Basra or Baghdad, as I was a militia target,” he said.

Al-Bakhit was not going to sit and wait to end up in the line of fire. He warned all of his colleagues, whose names were mentioned. “We all ended up outside Basra,” he said. “Except Abdul Samad. He stayed in Basra and told me he refused to leave.”

Read Also:

Social Media Bullying

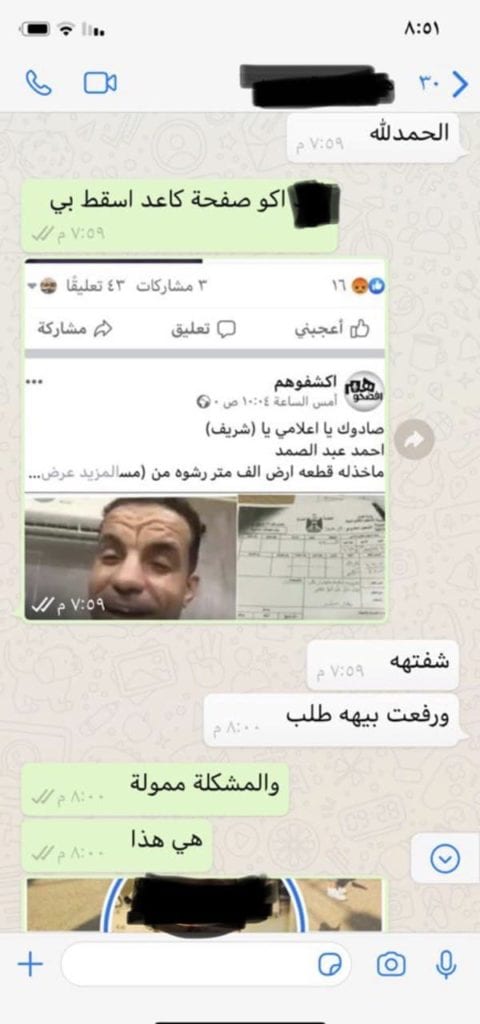

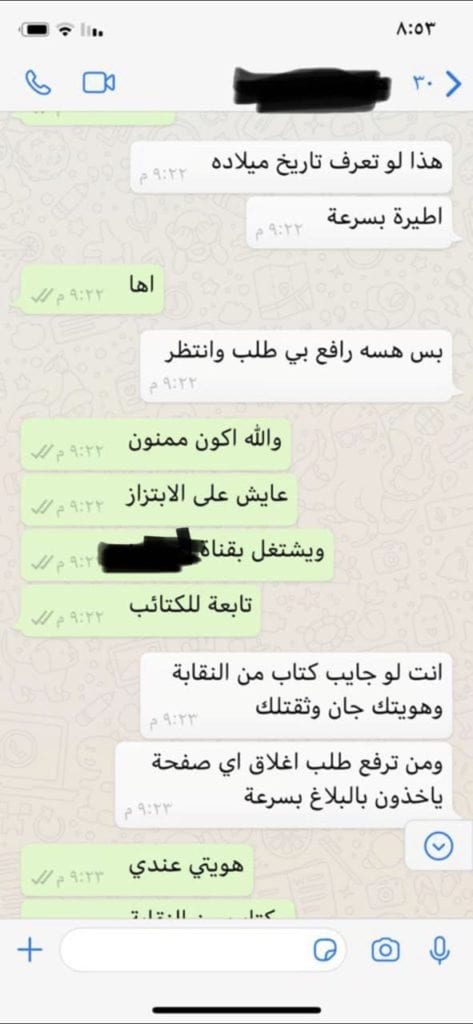

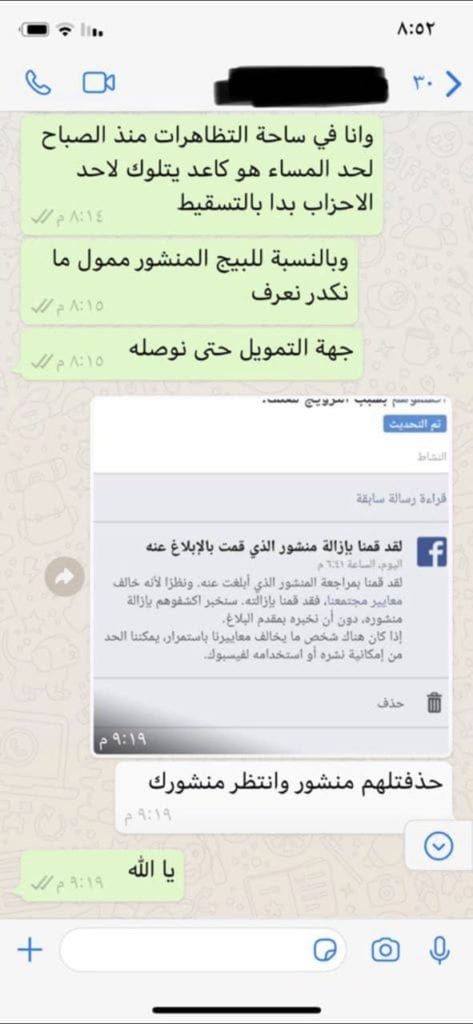

We managed to retrieve several messages from Abdul Samad’s phone, which he had sent via WhatsApp to a social media expert. Abdul Samad complained about being exposed to systematic provocations and “bullying.”

After the expert had explained some things, Abdul Samad specifically talked about one director of a website targeting him. “He is living of blackmail and works for a channel that belongs to the ‘brigades,” Abdul Samad wrote. “He would be at the sit-in square from morning till evening.”

“These conversations have not been part of the investigation into Abdul Samad’s killing,” said a source who has closely followed the investigation from the start.

Just before his death, following a campaign of random arrests targeting demonstrators, Abdul Samad had posted a video on his personal account, in which he sharply criticized the armed factions’ pro-Iran demonstrations outside the US embassy in December 2019 with a phrase that stuck with him after his death: “Our cause is a homeland issue. Oh, I do not consider you a homeland.”

Two days before his assassination Abdul Samad had furthermore tweeted a response to the daughter of Qassem Soleimani, who with Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis was assassinated in an American raid in Baghdad on January 3, 2020, in which he criticized “the Iraqis fighting on behalf of their eastern neighbor.”

Iraq ranks 163rd out of 180 countries on the 2021 World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders. Since 2003 no less than 490 journalists have been killed, according to the Federation of Journalists in Iraq. Hence, it should come as no surprise that Abdul Samad’s social media posts, his attacks on Iran loyalists, as well as his work critical of the ruling parties could be a reason to target him.

“Justice Will Not Sleep”

Over a year after the incident, Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi on February 15, 2021, announced the arrest of what is now known as the “death squad.”

“The death squad that terrified our people in Basra, spreading death in its beloved streets and killing innocent souls, have fallen into the hands of our heroic security forces, on their way to a fair trial,” Kadhimi wrote on Twitter. The four arrested gang members stand accused of killing Abdul Samad and Safaa Ghali and allegedly also carried out the assassination of 49-year-old activist Jinan Madhi Al-Shahmani (Umm Jannat). She and several fellow-activists were attacked by gunmen in civilian cars in Basra on January 22, 2020. “We got the killers of Jinan and Abdulsamad, and we will get the killers of Reham, Hosham and all the others,” Kadhimi tweeted. Adding: “Justice will not sleep.”

Who Are They?

Two days before Kadhimi’s tweet, news of the arrest was leaked offering some interesting details. The source was Ismail Musabbah al-Waeli who, on September 27, 2012, had seen his brother, former Basra governor Muhammad Musabbah al-Waeli, killed by death squad bullets.

In our meeting with him, Al-Waeli said other names belonging to the gang had not yet been revealed. “Not only that,” he said. “There are other death squads operating in Basra, some members of which have been arrested. We are now awaiting the results.”

On the day of Kadhimi’s tweet, the “Tactical Experts Cell” on its Facebook page published the following names regarding those arrested:

Aqeel Hadi and Heib Shukry, who is an employee of the Basra Oil Company

Hamza Kazim Khudhair Al-Eidani, a commissioner in the Basra Judicial Police

Khalaf Asaad Khalaf Mansour Al-Lami, a law student.

Haider Fadel Jaber Al-Rubaie, Director of the Technical Development Contracting Company

As for the fugitives, the Tactical Experts Cell mentioned:

Ahmed Abdel-Karim Al-Rikabi aka. Ahmed Tawisa aka. Ahmed Najat, the alleged gang leader

Alaa Al-Ghalbi

Abbas Hashem

Behind Abu Sajjad

Haider Shambousa

Ahmad Odeh

Bashir Al-Wafi

According to political analyst Hiwa Othman the death squads are clearly linked to pro-Iranian factions. “These factions do what they want,” he said. “They kill activists, target diplomatic missions with rockets. They do anything to strengthen non-state forces.”

An intelligence source confirmed four suspects had been arrested. “They work in a network of 16 people responsible for assassinations carried out in Basra.”

While Major-General Akram Saddam, Commander of Basra Operations, did not reply on our queries, Brigadier-General Thaer Issa confirmed that “investigations are ongoing and the pursuit of the fugitives continues.”

“Is it true that the wanted men fled to Iran?” we asked him.

“If they are inside Iraq, arresting them is our responsibility, but if they are outside the country the operation is beyond our authority,” he replied. “The government must then act through different bodies and coordinate with international organizations to arrest them and bring them back.”

The President of the Iraqi Citizenship Party, cleric Ghaith al-Tamimi, linked the assassinations to Iran in a broader sense: “We have information that trained assassination groups enter Iraq through Mahran to carry out their operations and then return. The members do not know who the target is. They just kill and return.”

A political source close to the prime minister said: “We do not rule out that some of the death squad members are outside Iraq.” Writer and journalist Sarmad Al-Taie believed that addressing Iran might curtail the death squads operating in Iraq and the region.

Taking Shelter

After much research, it became clear to us that, during the arrest operation in Basra, some of the death squad members fled their homes and took shelter in one of the presidential palaces, which the PMF use as their headquarters.

Ahmed Tawisa and Sayyid Alaa al-Ghalibi spent time at headquarters, according to an intelligence source. “And there is a possibility to a lesser extent that the accused Abbas Hashem was with them,” he added

The security forces in charge of arresting the gang members did not enter the PMF headquarters “to avoid a clash that might spark an internal battle,” according to several analysts.

Political analyst Hiwa Othman described the government’s handling of the suspects fleeing to the PMF headquarters as “weak.”

“It is not able to confront an institution such as the PMF, as Al-Kazemi lacks the required parliamentary backing, while there are large and influential political factions related to the militias,” he said.

Sarmad Al-Tai believed the consequences of a possible confrontation with such factions will be catastrophic, while he regretted “the issue has become part of political settlements.”

It was not possible for us to see the detainees’ confessions nor the investigation’s documents, yet two sources confirmed that the killers of Abdul Samad and Ghali were Ahmad Tawisa, Hamza al-Eidani and Alaa al-Ghalbi, while Abbas Hashem was responsible for logistics and monitoring the roads.

Where to Hide?

We searched for more information on the possible locations wanted people could run to. It turned out to be a thorny mission due to often conflicting information.

Most of the sources agreed it was possible to smuggle Ahmed Tawisa to Iran, due to the open borders and the country’s close proximity to Basra.

A source familiar with the investigations said that Alaa al-Ghalibi and Abbas Hashem had settled in the region of Jurf al-Sakhr some 50 kilometers south of Baghdad. Reportedly, the late Ammar Abu Yasser had helped them get there.

Jurf al-Sakhr is considered a “demobilized” military area, under control of the Hezbollah Brigades, since it was liberated from ISIS at the end of 2014. Ever since there have been plenty of rumors about secret prisons, weapon depots, suspicious business transactions, training camps and mass graves.

In more than six years three governments, including Kadhimi’s, have been unable to resolve the mystery of Jurf al-Sakhr. In March, the Prime Minister’s political adviser Mashreq Abbas attended a Clubhouse chat room session to answer questions from activists regarding the threats, as well as Jurf al-Sakhr.

Why has the government not been able to take back control? He avoided answering the question by saying: “It’s a thorny issue.”

Recently, a source close to the intelligence community suggested that Ahmed Tawisa and several other suspects were in Jurf al-Sakhr. Yet, later he said: “He has returned to Iraq and perhaps hid in Jurf al-Sakhar for a short period of time, but now he could also be in Baghdad.”

“They can move around with the identities they want and the cars they choose,” said a lawyer working on the militia dossier. “And so they can settle wherever they want.”

Inside the Green Zone?

According to the information we were able to access, the PMF and other armed factions also have a presence in the Bagdad Green Zone: mostly safe houses, but also several (semi) official buildings, such as:

The headquarters of the Popular Mobilization Authority.

The headquarters of the Popular Mobilization Security

A military headquarters opposite the presidential palace

The Directorate of Technical Equipment.

The house of Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, now in the hands of the Popular Defense Brigades An office of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (Khazali Network) under a cultural banner.

In addition, most of the PMF leaders live in the Green Zone with a large protection force. “Tawisa may be in one of the Green Zone’s fortified headquarters affiliated with the PMF,” said our source who closely follows the investigation.

It was not possible for us to see the detainees’ confessions nor the documents related to the investigation, but two sources confirmed that the killers of Abdul Samad and Ghali were Ahmad Tawisa, Hamza al-Eidani and Alaa al-Ghalbi, while Abbas Hashem was responsible for logistics and monitoring the roads.

Ahmed Tawisa

Ahmed Tawisa stems from a family with a history of violence. Ali Tawisa, Ahmed’s older brother, carried out an armed attack in the south of Basra in the 2006 sectarian war in which Sheikh Yusuf al-Hassan, head of the Basra Muslim Scholars Association and imam of the Basra Great Mosque was killed. Ali himself later died as a result of his injuries.

“Ahmed was recruited instead of Ali after the latter’s death,” said a source in the PMF.

Ahmed Tawisa is a very influential figure in Basra. He is considered a dangerous man and owns a series of investments in the governorate. He also has license for one of the port berths, many of which are under control of the militias.

According to a merchant who requested anonymity, the berth is used for smuggling arms and contraband.

In addition to a new home, which cost an estimated $600,000, Tawisa owns several other properties, and has a number cafés and restaurants on Basra’s Delegates Street. The rent for each ranges between $2,000 and 2,500 a month.

Haidar Fadel

Khalaf Asaad Khalaf

Hamza Al Eidani

In July 2017, Tawisa and three others were arrested: Ihssan Faleh Yaza, Yassin al-Wafi and Haydar Abdul-Hassan, also known as known as “Haydar Shambousa.” The arrests seems to have been related to a conflict of interest with the Peace Brigades of Muqtada al-Sadr, who had adopted a discourse different from that of the militias, which he called “impudent.”

His speech implied that Sadr and his militia had dislodged from the “rest of the pack.” In reality, it seems was a struggle over areas of influence and gains. In any case, the arrest of the “brigade members” did not last long.

Following a visit of the deputy head of the Mobilization Committee, the late Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, they were soon released. According to a security source, one of the intelligence officers working on the case was later targeted by an explosive device under his car. We tried to find out his fate, but people close to him refused to give any information, fearing for his safety.

In a video of the arrested members of the Peace Brigades shot during the investigation, Ihsan Yaza confesses to several crimes, in association with Tawisa, Yassin al-Wafi and Haydar al-Mayahi.

The Other Hamza …

A Hamza other than Hamza Al-Eidani, who was arrested as an alleged member of the death squad is Hamza Al-Halafi. According to Al-Waeli, he “also works in the Ahmed Tawisa group.”

Al-Waeli and a source in the Basra security apparatus both indicated that both Hamzas (Eidani and Halafi) as members of the Al-Fadhli Party of Muhammad Al-Yaqoubi and, before 2010, were involved in “assassinations, robberies, oil smuggling, kidnapping and extortion.”

Ismail Musabbah asserted that Al-Halafi “was very close to Sheikh Al-Yaqoubi.”

Our information indicates that Hamza al-Halfi is responsible for the economic file of the Hezbollah Brigades in Basra, controlling smuggling routes and imposing royalties. His influence extends to big companies.

Before the “death squad” was detained, another gang had been arrested, yet nothing was announced publicly. We tried to verify this information. A source close to Al-Kazemi did not deny this. Nor did he deny that the group was suspected of being involved in the assassination of activist Tahseen Osama on August 14, 2020.

This was confirmed by his uncle Hussein al-Shahmani who had previously stated: “One of those involved in the assassination left Iraq and then returned. He and six others are still at large and have not been arrested so far.” Al-Shahmani also confirmed that the victim’s father at the time had filed charges against all suspects by name. According to the investigation into the case, “big heads” in Basra were involved, but no serious action was ever taken.

Other Death Squads

Basra is a fertile ground for murder and murderers. The governorate has witnessed eight assassinations of activists, demonstrators and journalists since the start of the October 2019 demonstrations.

They are Hussein Adel, Sarah Talib, Ahmed Abdul Samad, Safaa Ghali, Tahsin Usama, Reham Yaqoub, Umm Jannat and Mojtaba Al-Zaji. This in addition to clan and sect-based murders and indiscriminate killings during protests.

“There is more than one death squad,” Al-Waeli told Daraj. “Two groups have been arrested. The first belonging to Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and the other to the Badr Organization.”

We had difficulty confirming this from our sources, yet no one denied what Al-Waeli said. According to him, the first was affiliated an Iraqi MP from the “Sadikon” bloc representing “Asaib Ahl al-Haq”.

The second group is led by Ahmed Abdel Zahra, who is affiliated with the Fourth Brigade of the Badr Organization. According to Al-Waeli, Abdel Zahra killed former Iraqi army officer Hussein Al-Bahadli and school principal Al-Sitt Fawzia for “their love for Saddam Hussein.”

“Abdel Zahra also confessed to killing Rahim Sajit, an officer in Saddam’s intelligence apparatus, and tried to kill Mazal Abu Harbi,” Al-Waeli added. “Both are from the Saadoun family in Basra.”

According to him, most of the detainees confessed to monitoring activists and journalists who supported the demonstrations.

A source close to Prime Minister Kazemi did not confirm or deny this, nor did he confirm or deny the existence of other detainees whose names have not yet been released.

Change the Investigation

Ismail Musabbah tried to highlight the political pressure that is being exerted behind the scenes to change the course of the investigation by replacing Brigadier General Mithaq, director of Basra Intelligence with someone closer to Iran and its Iraqi allies. They are reportedly pushing for Muhammad Jumaa.

Musabbah, used to be close to the famous cleric Muhammad al-Sadr, father of Muqtada al-Sadr, with whom he underheld a great rivalry. “Hadi al-Ameri, Faleh al-Fayyad, Abu Fadak al-Muhammadawi, Ahmad al-Asadi, and Ammar Abu Yasser, met with Minister of Interior Othman Al-Ghanimi and asked him to do so.”

In our interview with a source close to Prime Minister Kadhimi he described the situation as embarrassing. “He is under great pressure from armed pro-Iranian forces,” he said. “All government bodies involved in the case have been subjected to pressure following the criminals’ arrests.”

On June 25, 2020, less than two months after Al-Kadhimi assumed office, a counter-terrorism unit arrested 14 members of the Hezbollah Brigades in Albu Aitha south of Baghdad. The operation also seized arms and missiles.

At the time, the Prime Minister’s military spokesman, Major General Yahya Rasoul, claimed the operation aimed “to restore the prestige of the state.”

However, hours later the streets of Baghdad turned into a kind of Mosul at the time when ISIS stormed in: all kinds of cars with medium and heavy weaponry roamed the streets. They even reached the vicinity of Kadhimi’s main office, openly threatened him and his team, in order to see the detainees released.

After the incident, the word “pressure” became closely linked with the government and any issue regarding assassinations, murders, arms and fugitives.

The government has failed to indicate the source of such pressure. Yet, according to Hewa Othman “the pressure on the government stems from Shiite political leaders associated with such armed groups and factions or Iran, which sponsors them.”

Umbilical Cord

Meanwhile, the President of the Iraqi Citizenship Party, Ghaith Al-Tamimi, claimed the Al-Kazimi government had failed to confront such challenges. “Until today, this is a government that is complicit with the killers and armed groups,” he said. “And I do not think it has any intention to solve the case.”

Tamimi links the failure of the Al-Kazemi government to political pressure. “It exposes the umbilical cord between these armed groups and the authorities,” he said. “Meaning, there is a powerful political force within the state that practices this form of terrorism and they put pressure to cover it up.” .

After a year of investigations, and 2.5 months since the announcement of the “death squad,” the security services have not provided any detailed information about the detainees and their ties, as to which parties they belong and who stood behind them to protect them.

The authorities have furthermore refused to comment on reports of the wanted men being either in Jurf al-Sakhar or the PMF headquarters in Basra, and have been reluctant to confront Iran about them being possibly being there.

“It is clear that more than one faction is accused of the killings, and that the Hezbollah Brigades plays a role,” said a lawyer closely following the case. “And it is known that these parties are very loyal to whom they work with. If arresting some small faces was such a difficult task for the government and security apparatus, which consists of hundreds of thousands of individuals, how can they one day stop the big faces from being involved?”

“Simply revealing names is of no value, unless the parties to which they belong are announced, as these are not personal crimes,” he continued. “Unfortunately, all indications show that they will close the case as soon as it is internally and externally settled. They want the killers to continue to move freely. Meanwhile, we will not be surprised if we hear about the disappearance or flight of others tomorrow.”

Baghdad Investigative Team – This investigation was carried out by a group of journalists with the support of the Neri Foundation

Read Also: