Having heard the paternalistic advice of the President of the Lebanese Republic, who in November 2019 told demonstrators to emigrate if they did not like it here, a quarter of a million Lebanese have decided or were forced to leave the country.

The destination is not important. Indeed, all the other details are not important. Who and what do we leave behind? Where to go? These are details we have to store in a closed box until we can open it. But better not to open it.

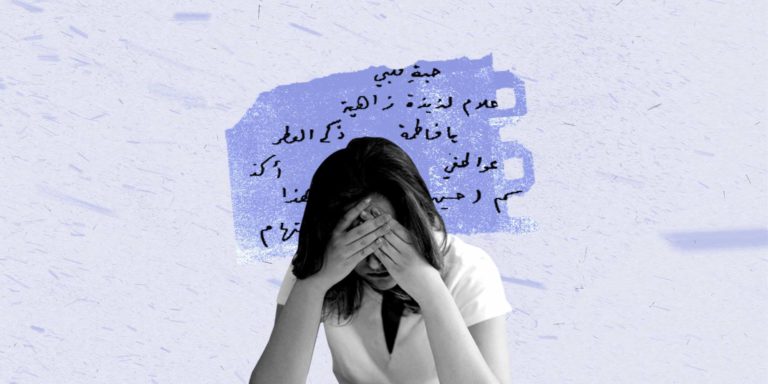

The important thing now is how to look at the camera, to show the tip of a smile with great precision, in order to preserve a minimum of dignity, so that we do not appear miserable, desperate, broken and destroyed on the photos that will appear in our passports.

It is okay for us to use our memories to restore luster in our eyes pending the realization of the desired image. Our memories will hide our faded features and will instead draw features that will convince the countries of the world that we are individuals who deserve a chance. The pictures will convince the countries of the world that we were expelled from our homeland not because of a technical defect, but the result of a one-sided love and relationship that we are unable to continue.

My head is filled with these pictures, pictures of passports issued to the Lebanese trying to get out. I know that the background of a passport photo has to be white, and it often shows us with a dull, pale face. But the details of the portraits are important this time, the portraits of the Lebanese. What did they wear on the day they were photographed? Their colors? Their accessories? How did they hide their failure and pain? Did they manage? How did they hide the feelings of guilt towards those who cannot leave and towards the elderly in their families?

What did they think while looking at the camera? And how did they choose the winning one from among the four or five the photographer took? On what basis did they select the chosen one, the one that will be immortalized, as dozens of copies will be printed for passport, immigration and work applications?

My head is full of these images. These passive images of over a quarter of a million Lebanese trying to convince those who review their files that they are among the best young people, and that the arbitrary expulsion affecting them is not their fault.

As I review the pictures and eavesdrop on their owners from afar, a wave of agonizing, yet calm, muffled sadness overwhelms me. A sadness that settles between throat and larynx. The only voice I hear while reviewing this huge number of photos is the one of Mahmoud Darwish.

Only recently I became aware that the bulk of Darwish’s poems, in which he wrote about departure, exile, occupation, occupier, memory, and the life we love, if only we were able to find a way, was with Beirut and Lebanon in mind. He wrote about us. He wrote what we lack the energy for to write. More than a quarter of a million passports for people who have family, friends, a lover or a sweetheart abroad, who will leave with one photo in their pocket trying to smile and a lot of broken photos and negative feelings in a tightly sealed black box at home.

I am now reading a portion of Darwish’s poem “Passport”:

All the birds that followed my palm To the door of the distant airport All the wheat fields All the prisons All the white tombstones All the barbed Boundaries All the waving handkerchiefs All the eyes were with me, But they dropped them from my passport

I realize I cannot stop switching words. Despite the uselessness of this exercise in logic, I cannot stop thinking about whether staying in Lebanon is limbo and leaving is death, or vice versa. Is there a difference in the first place? Between limbo and death? I am drowning in naive thoughts when I think about the possibility of leaving, and I like to use the word “exit” here.

For, despite the presence of more political and social terms such as “displacement” and “expulsion,” I am not strong enough to use the latter word when I think about the inevitability of exit, my exit. I’m afraid. I am afraid of this psychological weight I befriended, which has become part of me, and of which I became a part too. What should I do with it when my plane takes off to a faraway place? Will I be able to get rid of it before it lands in a new city, which is still unnamed and lacks landmarks?

The weight of myself does not confuse me here in Beirut. Dealing with it is easy, amidst this public confession at times and concealed at other times. A confession reconciled with the fact that we all endure misery and transcend brokenness and smile in the most painful moments, with the deep realization that we do not know what to do if our smile, in a moment of abandonment, betrays us and our body decides to adopt the natural context of things: sadness and tears.

Read Also: