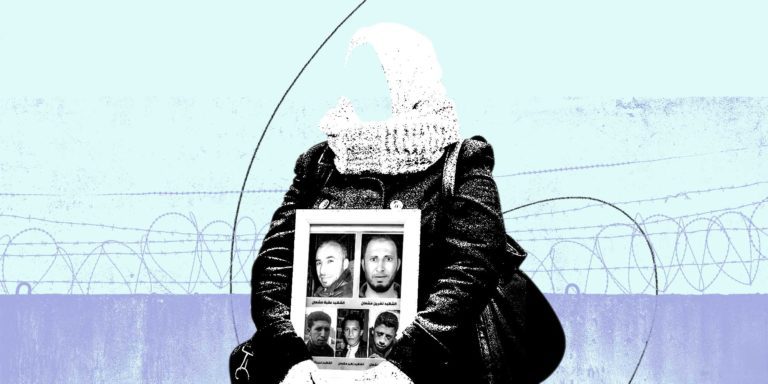

Mrs. Nawfa, 45, from Syria’s Raqqa, has been searching for the remains of her young son, Khalid, for the past three years, but to no avail.

The young man was killed during the clashes the city had seen before she left with the family in late 2017, and was hurriedly buried while the Global Coalition’s planes roamed the sky and gunfire from all sides filled the air.

In her daily search for the apple of her eyes, Mrs. Nawfa has repeatedly visited organizations concerned with missing persons, affiliated with the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria which controls the city, as well as the concerned individuals in the Raqqa’s Civil Council’s first Responders Team, but always came back empty-handed.

On a ‘sad’ Raqqa night, as she described, and with the help of her neighbors, Nawfa buried her son with her own hands while tears ran down her face. She never imagined burying him at this place, next to Al Taj Wedding Hall, the place where she wished to have his wedding party, surrounded by family and relatives.

The hall is located in south Raqqa, next to the old bridge. Before the war, it was a place to spread joy, a destination for the neighborhood and surrounding neighborhoods to have wedding parties, but it soon became a gloomy place shrouded in darkness, remembered sadly and sorrowfully by Raqqa’s people and all Syrians, because they buried their children and loved ones in a mass grave next to the hall and named after it, “Al Taj Mass Grave.”

Al Taj grave, or “the grave between bridges” as the residents call it because it’s located between the old and the new Raqqa bridges, was founded hurriedly by the residents at an open piece of land with red soil over an area of 4 dunams (around 4000 m2) at a crossroads next to a bypass road, in order to cover dead bodies during the fierce battles between ISIS and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which took control over the city on 17 October 2017, backed by the US-led global coalition.

“After the burial, I left the city as the battles got fiercer at the last days of defeating ISIS. After a few months, I was able to go back to the war-wrecked city, full of hope of visiting the grave that entombed his body so I could bury it at a proper place and be able to visit him, like others who lost their loved ones,” said Nawfa.

But Mrs. Nawfa did not foresee what actually happened. When she visited Al Taj mass grave, she did not find her son’s grave, as the place had transformed after moving the graves to another place. The once-famous hall was also completely removed by the end of 2017.

“The bodies were hurriedly exhumed from Al Taj grave, as I was told by a volunteer in the team working on exhuming the bodies, and the bodies were then moved to Tal Al-Bay’a Cemetery (east Raqqa) and were buried there. And when I asked him about my son’s body, he said we don’t know.. it might have been buried with the piles of bodies,” Nawfa added.

Like Mrs. Nawfa’s son, two successive global coalition airstrikes on Raqqa in the early hours of 12 October 2017 ended the lives of the 80-something Mohammad Fayyad Abu Seif and 16 other family members (Mohammad al-Fayyad and his three daughters, Ammar al-Fares, Yusri Abdul Aziz, Rezqeya (child), and Salem Hamad) and their neighbors, after the air raids destroyed his house and his brother-in-law’s (Hussein Hamad al-Fares) house in a narrow street at the middle of Raqqa, according to a detailed survey by Amnesty International.

According to the testimony of a source close to the family and the testimony of the surviving neighbors, the man had lived in his house for 50 years and refused to leave his house when the military campaign on the city began, but the series of airstrikes led to his death and burial in a mass grave close to the ruins of his house. The remains were later moved to a cemetery outside the city without identifying bodies and recognizing victims.

The international law deals with mass graves as “crime scenes” and considers exhuming bodies from mass graves in primitive ways to be one of the reasons leading to concealing the traces of the crime or why and how the victims were killed. Bodies, where they are, and how they look are evidence that should not be tampered with before forensic and legal examination as a part of investigations, as explained by legal experts.

Which now makes finding and identifying the remains of a victim that was buried in a mass grave and moved somewhere else, like the remains of Nawfa’s son, nearly impossible.

Dr. Mahmoud Kahil, forensic expert, argues that “the main problem with the process of moving mass graves is that it will cause the identities of the dead people to be lost and take away their families’ right to identify them.”

According to Fawaz Abd al-Ameer, of the International Commission on Missing Persons (IMCP), these diggings are unacceptable “and should be done by trained teams with adequate experience as they’re dealing with human remains at a crime scene.”

“In mass graves, there are no identification documents with the remains, not one piece of evidence, thus, the identified bodies are only the bodies that were buried in homes or were under fallen ceilings. The rest of the bodies have no papers,” says Yasser al-Khamis, head of the Syrian Missing Persons and Forensic Team in Raqqa Civil Council (First Responders Team).

In the year when al-Fayyad’s family and Mrs. Nawfa’s son were killed, another 1600 civilians were killed in air and artillery bombardment by the coalition according to documentations by Amnesty International and Airwars, after an analysis of 200 airstrike sites, while others were killed as a result of battles, bombardment, and blockade targeting the city.

Moving the Remains Again!

In April 2013, ISIS announced its control over Raqqa, and in July 2014, a US-led coalition to defeat ISIS was formed. In 2016, US-backed “SDF” waged a campaign to take control over Raqqa, and was able to take control over it in October 2017.

As a result of these battles, Raqqa became the most destroyed city of the modern age, according to OCHAA, and around 80% of the city was left uninhabitable.

Amnesty International says that over 2500 bodies were exhumed from Raqqa, most of which are of civilians who had nothing to do with the conflict other than living on the battlefield. The organization believes that around 3 thousand bodies remain under the rubble or in mass graves, most of which are also civilians.

Its report, “Syria: War of Annihilation: Devastating Toll on Civilians, Raqqa ─ Syria” published in June 2018, describes the civilian’s situation as they are “killed by the coalition forces’ missiles, buried under the rubble, and killed by random artillery shells of the SDF, in addition to those killed by ISIS’ snipers and mines scattered on escape routes, in a strange joint mission to murder.”

A night before ISIS’ exit, besieged civilians had to bury their dead under fire, and since burial in public cemeteries became impossible, residents turned to burying their families and neighbors in public spaces, playgrounds, parks, and even inside and next to their homes or in random mass graves. After the SDF took control over Raqqa, the First Responders Team’s “body exhumation” department began examining mass graves and moving the remains outside the city to cemeteries that were especially made to entomb the remains of those who were in mass graves in Raqqa.

Al Taj mass grave, south of Al Taj hall, from which the process of moving the remains took over a month, from 6 June to 26 July, was only one of 28 graves from which the team has exhumed and moved bodies to other places.

The number of bodies exhumed by the team involving volunteers, diggers, and coroners, was over 6100 bodies, only 700 of which were identified and given to their families since the team started working on 9 January 2018. Thus, leaving the identities of 5400 bodies, among which the remains of Nawfa’s son, al-Fayyad’s family, and hundreds of others, unknown after the main mass graves were moved to bigger cemeteries outside the city (Al-Shohadaa, Tal Al-Bay’a, and Hittin) to be put in the ground there.

In a report obtained by the investigative team, ICMP states that exhuming bodies in primitive ways destroys important evidence and further complicates identifying bodies.

Yasser al-Khamis, who led the search and exhumation team, believes that the role of his team was relief in the first place, and that they worked without training, due to the dire need to move the bodies from the city upon the request and urge of the residents, who started returning after ISIS’ exit. “When we entered Raqqa, we saw bodies in the streets. The city was all piles of bodies, and people lived on top of them. The bodies were, for example, in the streets, between houses and buildings, in halls, on berms, in the Euphrates, and among farmlands. Can you imagine that I’ve found 60 bodies in a wedding hall.. and witnessed constructing a building on top of 10 bodies in Harat Al-Badw?”

Gravedigger

On 21 June 2018, the sun rose on the only sound heard in a number of Raqqa’s neighborhoods, the sound of hand shovels digging the ground, interspersed with the sound of wind passing between the branches of nearby pine trees.

Diggers were then wearing light medical masks, holding blue bags to put body parts and bones in them, and starting to exhume hundreds of bodies from Al Taj mass grave which started to smell like death.

A First Responders Team volunteer, who worked with the team as a digger in this grave at these moments on that day, describes it: “I, and the rest of diggers, were writing down in a chart basic details, like the type of the body, and then put the body in a blue bag and put it in a small van to move the body to rebury them a few kilometers away.

“At Al Taj mass grave, we handed over 31 bodies to their families, after identifying the bodies by personal belongings and documents, or clothes and distinguishing marks. ISIS’ members were also recognized by their clothes.. The rest of the bodies could not be identified, so we numbered each body bag and buried them in Tal Al-Bay’a cemetery.

The digger did not know whether al-Fayyad and his family were among the bodies which remains were moved, due to the difficulty of determining the identity and sex of the victims. What he did know, though, was that only 31 bodies were handed over to their relatives, while 371 bodies of people killed and hurriedly buried here were lost in suspicious circumstances.

The digger’s words intersects with a document obtained by the investigative team on Al Taj mass grave, referring to the exhumation of 402 bodies from the grave, among which 298 male, 36 female, 45 girls, and 17 people whose sex was not determined, according to the document. “We had a choice: either all the evidence (bodies) would be gone or we work on moving them while documenting the reason of death. After two months of work, we had a database, which now contains 6100 bodies. We recorded everything about the bodies, such as any distinguishing marks like a broken tooth or anything of this kind,” Yasser al-Khamis said.

Change of Rules of Engagement

Raqqa city was called the capital of ISIS. At the time, it was overcrowded with civilians, and before the last attack, it was bombarded by the global coalition aircraft as part of rules of engagement specifically targeting ISIS, and limiting civilian casualties.

However, those rules of engagement have changed when the city was subjected to land blockade, and ISIS fighters retreated inside the city, as the land and air forces loosened up some restrictions by US laws, which resulted in a catastrophic destruction of buildings and properties, and the death of civilians, according to rights reports.

The investigative team obtained a copy of the reports recorded by the first Responders Team after exhuming bodies, including details of number of bodies recovered, work days schedule, and the body’s sex, but lack any reference to any additional information or distinguishing marks or even photos of the clothes found next to the body.

This might be explained by the fact that his team has, since ISIS’ exit, started working on exhuming the remains from graves using simple and primitive ways, driven by the requests of the residents who began to gradually return to their neighborhoods, as they lacked experience in this field, and they were mostly regular workers, accompanied by a coroner, and did not use anything but traditional digging methods.

Al-Khamis admits that “there was a hurry to exhume bodies in a nonscientific way, but this was due to the continuous complaints by the residents and their requests to move the bodies in order for everything to be back to normal, so we had to move these bodies.” Um Faisal, a resident of Raqqa, lost her husband in 2012 after he was arrested by the Syrian regime’s intelligence services in Raqqa. Her eldest son, Faisal (18), was her only support, the man of the house despite his young age as she says, but she did not get the chance to rejoice in his youth, as she lost him during the battles Raqqa has witnessed, during the global coalition forces’ bombardment.

A satellite aerial photo of Al Taj hall and a farmland next to it in 2015.

A satellite aerial photo showing the total removal of the hall building in 2017, as well as the mass grave.

In her humble and semi-demolished house, comprising of two bedrooms and a small kitchen, surrounded by the ruins of a city which has not yet recovered from war, she says: “Don’t reopen my wounds again, I’m trying to heal.. Faisal was my home’s pillar after Abu Faisal was arrested, but I lost both the light and the pillar.. We were displaced to Kasrat in al-Birk and stayed there for five months. We crossed the Euphrates with my two young children, after the coalition targeted the bridges, and al-Birk was not safe as the air forces were also targeting boats, it killed many people.”

When the woman returned to the city and when the residents began to move the bodies from Al Taj grave, she went asking for help in moving her son’s body to Hittin cemetery. “I could not find my son’s grave, because the residents began moving their relatives’ bodies before the Responders Team intervened to take them out systematically… So, by the residents recovering their relatives’ bodies and digging the ground, the grave’s features changed and I didn’t know where exactly Faisal’s grave was anymore,” she says.

She adds, “When the First Responders Team started to relocate Al Taj grave, I did not find my son’s body among those they were moving or have allegedly documented. Thus, Faisal died twice, once due to the US-led Coalition aircraft, and the second time when I could not find his grave nor his body”.

Al-Khamis, who still leads the Syrian Missing Persons and Forensic Team, which consists of 43 people (including doctors, data entry clerks, jurists, officers, and engineers), says, “As a team, we did not blur evidence. On the contrary, we documented all undocumented bodies. Legal evidence might be lost, but the body eventually was buried in the cemetery after knowing the cause of death, bombing or execution, or of any other reason. We are proud of our work… our team did not sin but made a mistake… and making a mistake sampling and locating is better than making a mistake and losing the traces of the corpses completely”.

Bodies Hurriedly Buried

The Investigation Team obtained videos documenting the transfer of mass graves, and we also monitored the steps of the relocation, where bodies are placed in bags and then buried in cemeteries like Tal Al-Bay’a, located five kilometres east of Raqqa and considered a public cemetery.

The International Commission on Missing Persons, an international organization working to develop effective procedures for the protection of mass graves, confirmed that the exhumation according to the Commission’s documents requires the analysis of skeletal remains of mass graves and the collection of information on missing persons, the ability to conduct excavations, and the skills used to identify corpses and determine the cause of death.

Thirteen families from Raqqa, who we have contacted and are living in different geographical areas near the city, explained to us that the majority of corpses in mass graves belong to those who were killed by the bombing of the city and the battles the city has witnessed in the last weeks before being taken over and were buried in difficult conditions. “The families of the victims and those missing in mass graves deserve to know the fate of their children and to have access to justice. Preserving evidence from these mass graves is an essential part of this process”.

The Black Stadium

Ammar Gh. (43 years), from the city of Raqqa and works as a microbus driver to transport passengers on the Raqqa-Deir ez-Zor road, recalls how ISIS arrested his cousin in 2016 and put him in Al-Akirshi prison. They then transferred him to the Municipal Stadium in Raqqa (Black Stadium), which the organization used as a headquarter, only to be killed there by the Coalition bombing of the stadium in June 2017.

According to the information that reached the family, the young man was buried in Al-Fakhikha mass grave, south of the Euphrates river (Al-Kasrat area).

The family now thinks that the body of their son is located somewhere in Raqqa, after the transfer of corpses from Al-Fakhikha cemetery to Tal Al-Bay’a cemetery at the beginning of the year 2020. Ammar says, “The family has tried to find where the body of my cousin is through the Responders Team but there were no distinctive traces…In Tal Al-Bay’a cemetery (to where the bodies were transferred from the mass grave of Al-Fakhikha), many corpses were not recognized by the people… They are very large numbers .. thousands of bodies which were not identified because there is no DNA testing device”, as he said.

The young man holds the international community and international organizations accountable for that, as they did not probably and quickly help to identify the dead and the fate of the bodies, as the capabilities of the forensic doctors are limited, the Responders Team work is slow, and there are no DNA testing devices.

“People are waiting impatiently”, he says. He pointed out that getting DNA test devices and identifying the bodies is the only way to determine the identity of more than 5 thousand unidentified bodies.

The Forensic and Missing Persons team has always complained about the lack of support and experts in archaeology and anthropology. Yasser Al-Khamis, who leads the team, agrees with what Ammar and the rest are saying and calls for the need to provide such devices that make the work of the Forensic team much easier. He says, “We need DNA test devices, as well as intensive training courses to deal with the situation”.

For his part, Fadel Abdul Ghany, Head of the Syrian Network for Human Rights, calls the Central Tracing Agency, run by the International Committee of the Red Cross, to start aiding in the search for thousands of missing persons in Syria, and trying to reveal their fate, which is a way to help determine the fate of the bodies and the missing, according to him.

Where is My Brother’s Body?

Fayez (41 years), from Raqqa – Ben Al-Jisreen, has lost his brother Salah (43 years) during the battles and fighting between SDF and ISIS near Al-Karajat area, at the end of 2017.

We got a number to contact him via WhatsApp to find out the fate of his brother’s body, and we found out that he is currently out of Raqqa and living in Turkey as a refugee. He agreed to speak on the condition that his full name not be disclosed because his family is still in Raqqa.

Fayez narrates the details of the story, recalling when his brother Salah left home one afternoon “to search for a place from which he could secure bread or anything to eat from the shops near Al-Karaj {the garage}, but he was late until after the Maghrib call and did not come back, while we were home waiting for him to come back, not knowing it was the last time we would see Salah”.

The tall buildings in the area and near Salah’s home were stationed by ISIS snipers, and these buildings were largely targeted by the Coalition forces and the SDF. Used by the snipers, these building were thus destructed, while Ben Al-Jisreen area was targeted by SDF.

Every moving thing is a target, according to Fayez. He says, “Salah did not come back that day and there was no way to communicate with him. A resident of the neighborhood found his body with a sniper’s bullet in his chest, near Al-Karajat area, and was able to pull his body with some neighbors. They buried him in the nearby cemetery, where the people and ISIS buried the dead”.

These days, satellite pictures offered by Google Earth show the locations of mass graves dug in the parks between the houses and neighborhoods.

While the former director of the forensic medicine authority in the Free Aleppo Governorate, Dr. Mohammad Kahil, considers that moving bodies from mass graves to other cemeteries without documentation is considered a crime on its own, in addition to the crime of murder. To this day, the family does not know who targeted Salah and put an end to his life, and Fayez does not know exactly what happened to his brother’s body after moving the graves outside the city after they left Raqqa and had the chance to go to Turkey through the city of A’zaz.

Praying on the Grave

In July of 2018, a Human Rights Watch report confirmed that, if workers continue to exhume the graves without appropriate technical training, equipment, and support, families may lose the chance to accurately identify the remains of their beloved ones.

According to the same report, “evidence related to the crimes in the area might be lost, including ISIS crimes and others”.

“We will not move any new bodies until we have received training, as well as devices to take samples from the bodies and reveal the reason of death”, Yasser Al- Khamis confirms the endeavour of his team in the coming days. Meanwhile, Um Faisal still hopes to find the grave of her son one day… Every day she goes to the place where he was first buried (Al Taj grave) and reads Al-Fatihah for his soul, then goes to where he was buried the second time (where his remains were transferred to the Hittin cemetery) and reads Al-Fatihah for his soul again, hoping her prayers will reach his soul and absent body.

As for Fayez, despite not knowing where his brother’s body is, who moved it, and how they did move it until now, he hopes to be able one day to stand at his brother’s grave, who left three kids behind, the oldest of whom is 8 years old and the youngest is 2 years old, to tell him what happened to their city, which was destroyed by the war.

The investigation was done under the supervision of the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism – Siraj.

Read Also: