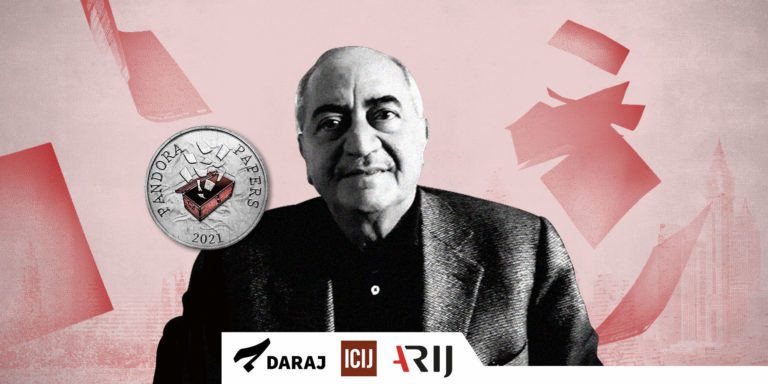

Asiacell Telecom was still celebrating the Ookla Awards it received earlier this year for its mobile services in Iraq, when a group of international journalists started digging in the documents leaked from Ericsson’s 2019 internal investigation.

It appears the telecom company carried out numerous illegal activities during its time in Iraq, especially regarding the Peroza Project it executed with Asiacell. Meaning “blessed” in Kurdish, the Peroza Project aimed to establish the transition from second generation (2G) to third generation (3G) of wireless mobile telephony

The team of journalists especially searched for Affan, who fell into the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), due to the Peroza Project. The Ericsson documents mentioned him. But it seems the company ignored him and abandoned him, having first pressured him to continue working in the region under ISIS control. The “Ericsson list” from the company’s confidential internal investigation into its work in Iraq were obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which shared them with more than 110 journalists from 30 news organizations in 22 countries around the world, including Daraj.

The documents reveal that the Swedish firm engaged in illegal conduct, including bribery, tax evasion, violations of the Code of Business Ethics (CoBE), as well as “possible” payments to ISIS. Ericsson’s net sales between 2011-2018 in Iraq amounted to some $1.9 billion.

His Neck in ISIS’ Hands

People working in the Iraqi telecom sector have generally been deprived of their basic rights regarding health care and social security. But Affan’s story is different. Employed by Orbitel, a subcontractor company contracted by Ericsson, the telecom engineer fell in the hands of ISIS, as he told the German NDR TV channel, one of Daraj’ partners in the Ericsson List project.

Timeline:

June 10, 2014: Mosul falls to ISIS.

June 11, 2014: Ericsson is looking for service providers to operate in Mosul and Tikrit.

June 18, 2014: Despite the recommendation of Vice-President Tom Nygren, to leave Iraq, Ericsson’s Rafiah Ibrahim and Tarek Saadi, advocated staying.

July 14, 2014: A meeting is held with Asiacell to continue working in Mosul by obtaining permission from ISIS. This resulted in ISIS capturing several Orbitel employees. Everyone was released except Affan.

July 15, 2014: Ericsson distances itself from Orbitel.

July 16, 2014: ISIS prevents Orbitel from operating until an agreement is reached with Ericsson. Orbitel then refuses to work in Dohuk.

July 17, 2014: Ericsson hires NGEN instead of Orbitel.

22 تمّوز 2014:July 22, 2014: Affan, the last Orbitel employee held by ISIS, is released.

According to Affan, Ericsson put pressure on Orbitel to continue working in Iraq after the invasion of ISIS. The choice was to either risk their lives or lose the contract. Orbital succumbed and continued working. Tom Nygren, Vice-President and General Counsel of Ericsson Middle East had in fact recommended to stop all work in Iraq (force majeure), but the team in charge of the Middle East, led by Malaysian Rafia Ibrahim and Jordanian Tarek Saadi, insisted on continuing, no matter the risks.

Until May 2014, Affan was working normally on the Peroza Project in Mosul. At Orbitel he had six teams under him to cover the region in terms of quality control, maintenance and network status checks.

Seeing the worsening situation in Mosul, Affan had preferred to stop working, but he was pressured by Ericsson and Orbitel to continue in order not to lose the project. Two days later a team member was kidnapped and later released. Ericsson knew about that case

“But their response was always that we had to complete this project, with or without you,” said Affan. “If you are in, you are welcome. If you are not, we will have others complete it. They didn’t care about us as human beings. How can I send someone to a place where he might be arrested, tortured or murdered?”

Soon after, another incident occurred. Again an employee was kidnapped and released within hours. Affan decided to stop working.

Ericsson and Asiacell then pressured him to take a letter from Asiacell to the ISIS headquarters in Mosul to facilitate the mission. Affan refused at first, but finally agreed. He delivered the letter, which included data on the project with Ericsson.

Shortly after, he received a call from ISIS member Haji Saleh, who was responsible for the telecom sector. He threatened Assaf, telling him that if he dared continue working “we will hide (kill) you.” And: “Either you come to us with your letter or we will come to your house.”

Affan still agreed to meet him, and was kidnapped. He was allowed to call the person in charge of security at Ericsson and informed him what had happened. Shortly after, Haji Saleh contacted him too and demanded money for Ericsson to be able to continue working in the region. The Ericsson employee hung up. Affan was taken home, yet placed under house arrest.

“During this entire time, my psychological state had sunk below zero,” he said. “I was thinking all the time about what will happen to me and my family.”

Ericsson and Asiacell did not contact him to resolve the situation. When Affan told Haji Saleh the companies did not respond, he decided to let him go.

None of the three companies involved in the ordeal, Ericsson, Asiacell and Orbitel, responded to the questions raised by journalists working on the project. For days, Affan lived in terror at the hands of ISIS, fearing every moment could be his last. His suffering did not end at the end of his detention. He is still traumatized, and remembers every day what happened to him.

Following his release, a friend in Kirkuk helped him cross to Sulaymaniyah, where he rented a hotel room after selling his car to be able to pay for his needs until he started working again. He tried working for Orbitel again. But he could not take it for more than a week, as he refused to work for a company that essentially traded his life for a deal. As for Ericsson, it is not just about Affan and some of his colleagues who passed through a similar experience in Mosul. There are strong suspicions that the company may have indirectly funded ISIS to pass on equipment and evade paying federal government taxes – apparently not caring that ISIS was committing crimes against humanity.

The Speedway: Tax Evasion through ISIS

“Ericsson illegally paid for Cargo Iraq’s “speedway” option to move equipment faster through Iraqi regions,” Roger Antoun, Customer Project Manager, is quoted as saying in the Ericsson List: “Ericsson dealt with [transport company] Cargo Iraq in 2016 and 2017 on instructions from Asiacell with the aim of circumventing the official custom duties, which increased from 10 to 15% to rose to 25%.”

The time frame and geographical regions covered by these transfers refer to areas under control of local militias, including ISIS, according to the Ericsson investigation. This happened in relation to the Peroza Project, which needed equipment for the 2G to 3G swap.

“The Ericsson equipment usually arrived through the Ibrahim Khalil border crossing between Turkey and Iraq, as it is manufactured in Europe,” said an employee of the border crossing, who preferred to remain anonymous. In other words, the equipment entered Iraq through Kurdistan.

In late 2015 and early 2016, disputes between the Kurdistan Regional Government and the Iraqi Federal Government intensified, as the regional government did not pay its dues to the federal government. This prompted the latter to impose taxes on goods and equipment coming to the federal regions, specifically at Al-Safra in the Diyala Governorate. Al-Safra became an official customs transit in October 2016.

A number of sources claim that, before 2018, collection of customs on Al-Safra was quite random. A former Iraqi official told Daraj that, at night, state-affiliated forces would leave the border crossing in favor of militias and non-governmental armed forces, including the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and Hezbollah Brigades.

To avoid paying taxes to the federal government, having already paid them in the Kurdistan region, many companies resorted to bypassing Al-Safra by heading from Khanaqin in the Diyala Governorate, passing through Naft Khana and along Mandali near the Iraqi-Iranian border up to Baqubah, the capital of Diyala, and onward to Baghdad and then Ramadi (in case of the Peroza Project).

Engineer Bassam Salem Hussein, Chairman of the Board of Commissioners at the Iraqi Communications and Media Commission (CMC), told Daraj that, usually, a foreign company would take care of securing equipment from abroad, while local companies handled the transport within Iraq. However, according to the Ericsson Documents, the responsibility for transportation in the Peroza Project was as follows:

1. Ericsson plans, orders and pays for all transportation of equipment inside Iraq

2. Asiacell handles customs clearance operations from Sweden to Iraq as the importer of the equipment.

The decision was made to separate the scope of transportation from fulfillment service providers and manage it as a separate activity, according to an internal Ericsson report, which furthermore confirmed that Cargo Iraq, SLS, and a third company called Al Tahaduth were involved in evading official Iraqi taxes in the process. The transfer of equipment from Erbil into central Iraq was done without due diligence, according to Ericsson’s normal supplier selection process. Cargo Iraq offered two transportation options:

A – The Speedway option

B- Normal (Legal) Method

The first contact between Ericsson and Cargo Iraq took place in January 2016, however the documents indicate that Cargo Iraq was not yet registered as an authorized Ericsson supplier. It was paid in cash through Security and Logistics Services (SLS), which was an authorized Ericsson supplier that had its first contract with the company in February 2013.

Bills from Cargo Iraq to SLS totaled $171,000 between the third quarter of 2016 and the second quarter of 2017, which were paid in cash by SLS and reimbursed by Ericsson through purchase orders, for fictitious services worth $6.7 million between 2013 and 2019.

The authors of the investigation sent questions to Cargo Iraq and SLS, but the companies failed to reply.

“Although there is no confirmed evidence of bribery or payments to facilitate work or possible illegal financing of terrorism, there is evidence indicating illegal customs bypass and passage through ISIS-controlled areas,” according to the Ericsson List. “By avoiding official customs, and opting for transport through areas controlled by militias, including ISIS, it cannot be excluded that Cargo Iraq was involved in facilitation payments (to customs officials) and potential bribery to finance terrorism.”

After Ericsson stopped working with Cargo Iraq and SLS, Al-Tahaduth started providing their services at a higher price. Gagandeep Kohli, a former Ericsson telecom engineer who worked on the Peroza project between 2014 and 2017, said in an interview with partners of ICIJ, that the project did not stop during the period ISIS was in control. In fact, the project ended in 2017.

“Ericsson outsources the subcontractors and the subcontractors do whatever they want, pay ISIS or the government. Ericsson doesn’t pay them. The subcontractors do all the deals. Ericsson won’t put its name in bribery or ISIS. “It’s very difficult to blame Ericsson.”

Telecom Towers

As for the telecom towers under control of ISIS, the question remains if the telecom operators paid the organization to safeguard the towers, as was the case during the days of al-Qaeda in Mosul. According to witnesses from the region, the towers were only destroyed in the last six months ISIS was in control.

Bassam Salem Hussein of CMC confirmed that state losses in the telecom sector were enormous during that period. But neither CMC nor the telecom companies shared the value of their losses.

Iraqi Minister of Telecom, Arkan Shihab Ahmed, stated that there are no specifications for the losses. There are two types of losses: direct (in infrastructure) and indirect in the form of lost income from not using the network.

Iraqi investigative journalist Dlovan Barwari in an interview with Daraj explained how business was done when al-Qaeda was in control. Before the establishment of ISIS and its taking control of Mosul al-Qaeda collected some $5 million monthly, specifically in the form of royalties on special interests, including those of the telecom companies.

Through a secret list provided to him by an al-Qaeda member, Barwari showed that Asiacell was continuously paying a “tax” to protect its towers in Nineveh Governorate, after it had tried to refrain from payment in 2008. The response of al-Qaeda then was to blow up dozens of towers within months.

Ali Muhammad Abbas, a fifty-year-old Iraqi citizen residing in Mosul, spoke of the difficulties and fears they faced during that period, as he risked his life to communicate with the outside world and inform people of the situation inside Mosul. The network at the time was very weak, he said. But he used to go up to the roof of the building at two in the morning to pick up a weak signal from Korek. According to him, however, members of ISIS, especially foreigners, were communicating with their families using the same networks.

Read Also:

Did the US turn a blind eye?

On December 6, 2019, Ericsson agreed to pay total penalties of more than $1 billion to resolve the government’s investigation into violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) arising out of the company’s scheme to make tens of millions of dollars in improper payments around the world.

This includes a criminal penalty of over $520 million and approximately $540 million to be paid to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in a related matter. An Ericsson subsidiary pleaded guilty for its role in the scheme.

“Today, Swedish telecom giant Ericsson has admitted to a years-long campaign of corruption in five countries to solidify its grip on telecommunications business,” said U.S. Attorney Geoffrey S. Berman of the Southern District of New York. “Through slush funds, bribes, gifts, and graft, Ericsson conducted telecom business with the guiding principle that ‘money talks.’”

Ericsson had entered into a three-year Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA), during which criminal charges against the company were suspended, provided Ericsson made reforms and continued to cooperate with the US Department of Justice.

Ericsson was held accountable for illegal activities in five countries: Djibouti, China, Vietnam, Indonesia and Kuwait. The firm’s work in Iraq was not included in the 2019 agreement.

Was the US Department of Justice aware of the violations that occurred in Iraq, which may include paying money, indirectly, to a terrorist organization that committed crimes against humanity? And if they did not know, why did Ericsson not abide by the 2019 agreement?

According to a recent Reuters investigation, the US Department of Justice was aware of Ericsson’s Iraq investigation. Yet, it refused to answer questions from journalists working on the project. Having sent comment requests to Ericsson, the company issued two official statements acknowledging its corrupt behavior in Iraq. They indicate that the internal investigation had found serious violations of rules of compliance and the Code of Business Ethics.

The investigation found evidence related to corruption, including: making a cash donation without a clear beneficiary, paying a resource for unspecified work and documents, using suppliers to make cash payments, funding travel and inappropriate expenses, as well as conflicts of interest, non-compliance with tax laws, and paying intermediaries and using alternative transportation methods to circumvent Iraqi customs, at a time when terrorist organizations, including ISIS, were controlling some transport routes.

In media statements the company has also admitted the possibility that its funds may have reached ISIS. While Ericsson claims it has taken action against those involved in corruption in Iraq based on its internal investigation, some of those who were involved are still with the company. Some have even been promoted. Elie Mubarak, the Key Account Manager (KAM) for Korek at Ericsson at the time, was promoted to the rank of Country Manager in Iraq, even though he had been involved in several abuse cases. In the end, only the on-the-ground workers, especially employees of subcontractors, such as Affan paid the price for Ericsson’s stubbornness and disregard for human life.

Read Also: