About a year ago, Lebanese writer and publisher Lokman Slim was killed. At the time I wrote an article that, and I thought it would break my isolation from writing in Arabic, but in fact only ended up deepening it.

It is the isolation that has haunted me ever since my brother was killed in Istanbul three years ago. Until today, no one knows whether he was killed, whether he killed himself, or whether it had been a natural death.

No one knows and no one cares. So, what difference does it make?

The dead, individually and in groups, among the Syrians and many other people in our miserable Middle East, are countless. Since the day my brother died I am no longer interested in writing, or anything else. I only write what my work requires, in Dutch, for I live among its people.

It is a language in which I can say anything without feeling like I actually said anything. Since my brother’s death in Istanbul, I’ve split into two. One was defeated by his death, the destruction of Aleppo, the slaughter of the Syrian revolution, and the survival of Bashar al-Assad as head of a regime, which stands for everything I once feared and from which I have been running from all my life.

The other stands victorious in his escape to a European safe haven, and the freedoms he seized after a hard and lonely journey that almost also feels like defeat.

I wish my brother had not died. I wish for many other things over which I have no power. I wish to be able to be who I am, with my family, and in my country. But these are surreal wishes.

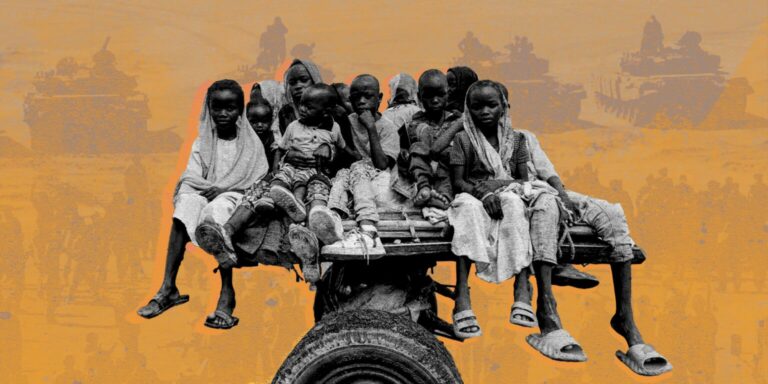

It only takes seeing Syrian children in refugee camps between Idlib and Arsal, covered by snow, to know just how surreal my wishes are. Bashar al-Assad sitting on his throne in his palace to this day, furthermore confirms that fact.

I no longer call this unfair. Injustice, no matter how severe, still bears the meaning of what can be seen as a light at the end of the tunnel, or some other cliché that cannot resolve the memory of a Syrian child now walking barefoot in this camp or that, nor the memory of my fallen brother.

I now simply call this pain. It is a nagging pain that is never tired of nagging. It is a pain I carry with me here, the place I ran to, where I supposedly live free.

Sometimes it pushes me to live freer and happier. Then it pulls me back again, along with my life and my freedom, clipping at the strength with which I have always fought to become what I want to be.

In all of this, I am neither less nor more than others. Neither in my freedom, nor in my defeat nor my victory. Through all of this, I am merely a survivor.

And as I survive, I live to see the price survivors keep paying every day. The price they pay for those who could not survive.

I also would have liked, despite what happened and is still happening, to keep writing in this language, and to keep writing for its people. But this language is the manifestation of my defeats. What did we benefit from her? Oppression, shackles, fear, blood, exclusion, expulsion?

It only takes seeing Syrian children in refugee camps between Idlib and Arsal, covered by snow, to know just how surreal my wishes are. Bashar al-Assad sitting on his throne in his palace to this day, furthermore confirms that fact.

I no longer want this defeat. I reject it even if it sits in every cell of my body. I refuse it even though I would like to have written one last letter to my brother to prevent him, and us all, from death.

As for my Dutch, I write about what I have obtained in this country since I sought refuge here years ago, about the rights and freedoms I exercise, and the respect I get, even from the most vicious people, who reject my presence in this country.

Respect for rights and freedoms. These are the Arabic language words. Neighboring words, drawn in and added to. In Dutch, it is life itself. My life. From morning to evening.

When I say I am free in Arabic, I feel as if I am writing a nominal sentence, with a piece of news omitted from it. But when I write or say it in Dutch, I add a base to all the phrases with a noun.

This was most evident on the day I obtained my Dutch citizenship, in the fall of last year, after six years of asylum. The day the civil servant, who was going to hand me my Dutch passport said: “Sir, you have become Dutch, your temporary ID is no longer necessary.”

I was overwhelmed with a sense of pride, security, and freedom that I had never known before I came to this country. I remembered my country of humiliation, in which we were raised under the rule of the Two Assads, father and son. And I felt sorry for my brother, for my language, and for all of us.

We have not known a greater defeat than the rule of Assad. It is the mother of all defeats. And my Dutch passport is my proof of liberation from this defeat and from the tyranny of the Assad regime and the tyranny of my conservative society, which did not accept me for my free mind.

Today, on yet another commemoration of the forgotten Syrian revolution, only days after the commemoration of the killing of Lokman Slim, and only days before the commemoration of my brother’s death in Istanbul, I return to this language, Arabic, without any aspirations or security.

I’ve returned one last time to say that I live here now, as I have always wanted to, as I am, and I am free. And that is a very good thing.

Read Also: