The Lebanese political party Citizens in a State (MMFD) only needed to hang a banner with an electoral slogan in the southern suburbs of Beirut for Hezbollah to mobilize against what it considered an attack on its area of influence. The banner was almost immediately removed.

The banner did not even send a clear anti-Hezbollah message. It used the words of the party’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah to pose a question: “The candidacy of Marwan Kheireddine … isn’t the corrupt like an agent?”

The question addressed one of the Hezbollah contradictions ahead of the May elections: on the one hand Nasrallah’s stance on corruption, and on the other working with his allies to succeed in the elections. This includes the banker Kheireddine, who stands accused of stealing depositors’ money.

The MMFD question invites the Hezbollah public to think about the party on the basis of Nasrallah’s own words. Party loyalists treated the banner as a security breach. Activists on social media responded by attacking MMFD, accusing it of only targeting Hezbollah.

The incident shows how Hezbollah is keen on imposing and maintaining visual dominance, on having complete control over public imagery, in its streets and neighborhoods.

Soleimani and Mughniyeh

In the runup to the elections, Hezbollah has replaced posters and pictures along the Beirut airport road. Images of Qassem Soleimani and other leaders have made way for the slogan: “We will protect and build.”

In addition, while calling the election of Hezbollah candidates a religious duty, pictures of the party’s dead began to circulate, accompanied by the phrase “My voice is the voice of a martyr.”

Since its inception Hezbollah has excelled in using visual language for its political project. It is well aware of how visuals can help spread a narrative, meet the needs of its audience, and, at times, attack opponents in Lebanon and abroad.

The party is proud of its media and propaganda. Its media crews do not leave the side of its fighters. According to Hezbollah TV channel Al-Manar, Hezbollah’s former number two Imad Mughniyeh and former military commander Mustafa Badreddine played an important role in establishing the party’s military media.

After both were assassinated in Syria, Mughniyeh became a popular icon for Hezbollah. The party used his portrait to introduce its audience to the leader, who remains hidden. Although important, Mughniyeh never received the same honors as Qassem Soleimani, former commander of the Iranian Al Quds Force.

Hezbollah hung numerous pictures of the Iranian military leader along the Beirut airport road and erected a statue of him in the city’s southern suburbs, as well as a copy of it on the Israeli border.\

The boom in Soleimani imagery since his murder has several functions. In addition to the emotional aspect, related to his killing by the Americans, and his personal relationship with Nasrallah, the photos aim to sanctify him and emphasize that his assassination did not cause damage to or defeat the axis of resistance.

In that sense, it should not come as a surprise that one Hezbollah supporter attacked people who dared touch Soleimani’s picture at a Beirut book fair, while Hezbollah media considered one young man’s attempt to destroy a Suleimani image a “fascist invasion.” He was severely beaten.

To Hezbollah, its imagery is as important as its military arms. Its arms could not have the power they have, were it not for the power of the image accompanying them.

One of the pillars upon which Hezbollah was built is imagery. The party has employed it in the sanctification of its people and weapons, in amplifying its actions and achievements, in producing a power base among its supporters, and creating a link with Iran.

Since the establishment of Hezbollah in the 1980s, the camera has always accompanied the gun. At times, it almost surpasses it even. Hezbollah has used the camera to document the actions of the gun and create an aura around it.

The Lebanese resistance fighters who preceded Hezbollah in the fight against Israel did not carry cameras. So their achievements have largely been forgotten. Hezbollah realized the importance of the image to announce itself as an effective player on the battlefield, gain the support of the people and intimidate the enemy. With time, the use of the image expanded as the party’s role expanded both internally and externally. It was used with allies and opponents, to mobilize a hesitant public for the war effort in Syria and deal with the economic collapse Lebanon is facing. And the image is still a tool for demarcating the party’s spheres of influence and an indicator of its expansion.

Read Also:

Iranian Convoy

The propaganda methods Hezbollah uses are very similar to those made famous by the United States and adopted by its military. They are rooted in the methods of Edward Bernays, known as “the father of spin,” who relied on psychology to lay the foundations of what is now known as public relations and marketing.

Through pictures and videos, the party addresses the masses. It stimulates fear among them, reassures them, tickles their religious feelings, and stirs their feelings of guilt for failing to sufficiently support Imam Hussein.

One method that can be traced back to Bernays is fabricating an event to be covered by the media to obtain a positive image, which is then used and circulated to market an idea the party prepared and promoted.

This is what happened with the diesel imported from Iran. The party paved the way for the event through Nasrallah’s speeches and then called upon the media to cover it. The Iranian diesel trucks were received with rocket fire and rice and the convoy appeared in the media far and wide. Thus the party managed to circulate its narrative about “breaking the American blockade.”

On the ground, however, the crisis persisted and the people’s suffering to obtain diesel and gasoline continued.

Early Days

Even in Hezbollah’s early days, the party attached great importance to images and banners. It seems it was even thinking about the scenes its cameras would capture before carrying out a military operation, such as storming Israeli positions in occupied south Lebanon.

Among the most prominent of such operations, which are still remembered, are the 1986 storming of the Sajd site and the 1994 planting of the flag at Dabsha. They confirm the importance of the image in captivating the public, and show the aim of storming the sites was not just military. The party risked the lives of its members carrying cameras to capture the moment of planting the flag. Images that were later used in campaigns aimed at attracting Shiite youth to join its ranks and destroy the morale of Israeli soldiers.

With time, similar scenes were repeated. It contributed to Hezbollah’s success in gaining south Lebanon’s support in resisting Israel. Many people were hostile at first, especially the sons of the Amal Movement (Amal), whose leader at the time described the party’s founders as “Kharijites,” as they had left Amal and turned against it.

Iranian Industry

In her book Off The Wall, Zeina Maasri, Associate Professor of Graphic Design at the American University of Beirut, analyzes the use of posters by Lebanon’s political parties during the Civil War, including Hezbollah’s.

According to Maasri, Iranian poster design was the most influential source for Hezbollah. It painted an anti-imperialist struggle and used a political-religious discourse, appropriate for the party and familiar to its Shiite audience, as it shares a history of religious and cultural practices with Iran.

The Shiite religious-political discourse, which was established during the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, facilitated the transmission of the aesthetics of Iranian posters and their re-adaptation within a Lebanese context.

Examples of contemporary Iranian political art were among the means of support Iran provided to the party. According to Maasri, members of the Hezbollah media office received training in technical skills and poster design from Iranian artists who came to Lebanon and held workshops. They even designed some of the first Hezbollah posters between 1983 and 1985, as well as the Hezbollah logo. It is a design based on the Revolutionary Guards logo.

During that period, pictures of the party’s dead were venerated. The image of a dead man was accompanied by a narrative filled with religious sanctity, urging young people to wage jihad. The dead were accompanied by “imaginary backgrounds derived from the repertoire of religious imagination in Shiite mythology and history,” according to Maasri.

So, the party’s posters were launched with Iranian support and content. And they did not address the resistance to the Israeli occupation in South Lebanon as a Lebanese or Arab issue, but rather as an Islamic one. At the same time, pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini began to spread.

With the expansion of the party’s influence, its use of pictures and posters began to expand. Today they dominate most Shiite-majority areas, especially after the decline of Amal, which was founded by the Shiite cleric Musa al-Sadr, the main representative of Lebanon’s Shiite community before the emergence of Hezbollah.

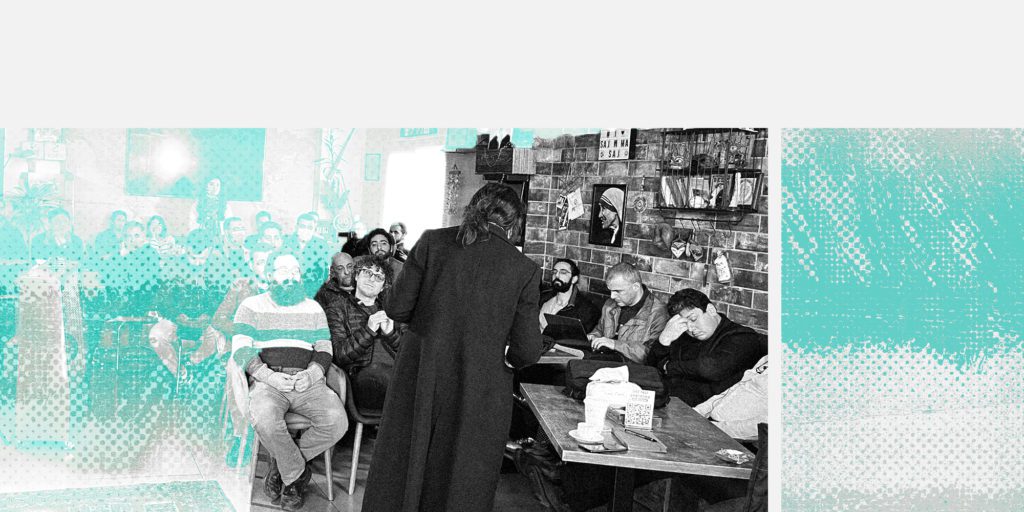

In areas dominated by Hezbollah and Amal, their public images work to exclude “the other.” Those not loyal to either party are prohibited from hanging their pictures or posters and expressing themselves. There is no logo or picture to raise except those belonging to the strongest.

Thus there is no acknowledgment of the right of the other to exist. Images become like an aura and impose a moral authority in their surroundings. As for those protesting the visual language, even if only symbolically, it is seen as a rebellion and met with repression and physical harm. Disputes over pictures have regularly led to injuries and even deaths.

Divine Victory

During the 2006 war with Israel Hezbollah used images to raise the morale of the residents in areas targeted by Israeli bombings and put pressure on Israel to break its soldiers’ morale, which had a big impact on the war and the negotiations accompanying it.

Read Also:

Take the bombing of the INS Hanit, a Sa’ar 5 class corvette of the Israeli navy. The missile attack coincided with a speech of Nasrallah, who actually gave the signal to attack during his speech, while cameras were watching. After that, the number of people who died or the extent of the damage caused to the battleship did not matter as much as the act itself and the way it was presented to the public.

The videos delivered the message that Nasrallah was a man who kept his promise. That phrase is still used, although these days in two ways. On the lips of Hezbollah supporters, who still use it in a literal way. And by opponents who use it in a taunting manner, as they consider Nasrallah to have broken his promise in the fight against corruption.

Also, before announcing the ceasefire between Hezbollah and Israel on August 4, 2006, Hezbollah had prepared posters celebrating what it considered a victory, and distributed them among the displaced before they returned to their homes and villages.

Again it is as if the party imagined the scene before the camera lenses picked it up. In this case, the scene of people returning home holding up pictures of Nasrallah, accompanied by the words “Divine Victory.”

The Syrian War

In the years following 2006 the use of the image further expanded and it was no longer to the same extent focused on Israel. The “liberation of Jerusalem” took a detour. The camera and the rifle moved to several places within Lebanon and abroad, which diversified the function of the imagery, as well as the target audience.

During the Syrian war, the party aimed to urge its followers to fight in Syria and urge their families to encourage them to do so. Its pictures glorified the dead and linked them to the Imams. It aimed to turn “death in Syria” – in defense of Sayyidah Zainab’s shrine – into a matter of pride for Shiite youth.

Over the years, the pictures of the dead multiplied in the streets, and gradually their colors faded through neglect. The pictures in the neighborhoods aimed to address their residents to recruit more fighters by encouraging them to imitate the dead man by portraying him as the one who transcends them. The pictures were accompanied by bragging speeches, inviting young men to join the convoy attributed to the Shiite imams and follow their path.

The Al-Manar channel revealed details about how Hezbollah’s media worked during that period, how it “developed its propaganda methods” and coped with the war. Its cameras were accompanied by tanks, artillery batteries and drones, and were placed on the helmets of fighters storming in, so that the military became a direct source providing Arab and international media with videos of the operations. According to Al Manar, the videos were produced during the war in the outskirts of Arsal, “managed by a special body at the highest level,” which included people who had supervised the filming of the storming of Israeli positions.

In Maaloula, the party wanted to send a message to the Christian public and spread a narrative that it is protecting them, so pictures of fighters saluting the statue of the Virgin were released. To this very day, there is a political investment being made in such images, especially in debates with Hezbollah’s main Christian ally, the Free Patriotic Movement.

When the operation “Dawn of the Outskirts” managed to expel ISIS from the outskirts of Arsal in green buses, Hezbollah’s military media published a picture that aimed to shorten the story. It showed the Hezbollah logo clearly visible on the shoulder of a fighter, looking at a Lebanese army division deployed in the area. This one picture tells us Hezbollah was the one leading the military operation and liberated Arsal with the Lebanese army under its supervision, command and protection.

The image of the army weak and powerless without Hezbollah is one the party has always cherished. It uses it to confront those who demand Hezbollah hand over its weapons and convince the public there is no alternative to its weapons.

The Economic Crisis

The economic collapse Lebanon has witnessed since 2019 also affected Hezbollah, its image and its use of the image. In addition to the image of the Iranian fuel trucks mentioned earlier, it attempted to absorb and channel people’s anger due to the deteriorating living conditions, by spreading images of the rations, funds and food aid it provides in the areas under its control.

With the increase in voices accusing the party and its supporters of indifference to others, because they receive fresh dollars, the party has tried to counter resentment. The image of its fighters lined up inside the Sayyid al-Shuhada compound was replaced by the image of gallons of oil and bags of food in front of a picture of Nasrallah.

The image aimed to reassure the public, which feared hunger, and ensure it would not rise up against the party. The food aid images were accompanied by the launch of the Al Sajjad ration card, which allows the holder to purchase goods in designated stores at cheaper prices than in regular stores.

The True Face

The fabricated, altered and manipulated images hide the true face of Hezbollah, its fighters and its supporters. It only shows what the party wants to show, which is the nature of PR and something all parties do.

However, there have been several incidents, in which the party lost control over events, proving unable to monopolize the image and control the message. Human features of its fighters appeared, which the party had always tried to hide in order not to overthrow the mythical quality it had tried to establish through its images.

In August 2021, residents of the town of Shwaya in the district of Hasbaya, south Lebanon, seized a rocket launcher from Hezbollah. One of them filmed the scene, showing fear and confusion on the face of a Hezbollah member.

The rocket launcher looked different from the camouflaged one that the party usually shows in photographs. Party supporters on social media were quick to deny the look of fear on the fighter’s face. They considered it to be an expression of “surprise.” In October last year, another image of a Hezbollah fighter appeared. It seemed like a non-professional fighter. Arab TV’s live broadcast of the clashes in the Tayouneh area showed a Hezbollah member being killed after advancing to fire a rocket-propelled grenade at a residential building.

People who saw the scene at first thought he was a member of Amal, given his unthoughtful and inexperienced rush. Later it turned out he was in fact one of the Hezbollah fighters who had gone to Syria. The two images showed a side the party had tried very hard not to show: fear and a lack of professionalism. The party tried to counter it by covering the image with a text and issuing a video showing the party’s ability to fight in the snow.

When comparing the images produced by Hezbollah and those “stolen” from certain events, it appears that the strength of the Hezbollah image lies in the party’s ability to produce it alone and control what and how it is published. It shows the ability of a masterfully crafted image to create power and nurture strength, and how it is a concern for the strength and authority it represents that, when touched or shaken, the image may falter.

Read Also: