Flaring is the act of converting methane into compounds such as carbon dioxide. It produces no distinct odor, color, and in some cases, not even any fumes, which makes it more difficult to notice. However its health-related and environmental impacts leave a very consistent mark.

Only a few miles away from Port Said Airport, following the Mediterranean coastal road to Damiette, one can easily notice the blatant contradiction between modernization and conservation.

There, Ashtum El Gamel, a protected wetland reserve and Egypt’s most important bird area, faces a vast industrial complex made of hundreds of gas pipes, dozens of processing units, and a few burning torches where methane emissions have more than doubled in the past ten years, according to an analysis made possible bySkytruth, a nonprofit environmental watchdog.

Despite Egypt’s alleged efforts in cutting down flaring emissions from the oil and gas industry on a national scale, the country’s entire Mediterranean coastline has seen no improvement in reducing said emissions, which have been maintained at a steady level through hydrocarbon extraction sites and refineries. In fact, flaring rates have doubled in the Ashtum El Gamel region compared to 2017, and have also tripled in the region of Damietta’s port.

Flaring remains steady on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast

The Mediterranean basin has long been called a biodiversity hotspot, with over 5,000 to 25,000 species and an outstanding flora diversity of which 60% are thought to be endemic, according to the Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Mediterranean Area (PRIMA).

While transport and tourism have been identified as some of the main threats for biodiversity in the Mediterranean region, according to Kasia Marini, scientific officer for MedECC in Plan Bleu (Regional Activity Centre of Mediterranean Action Plan), methane flares on the North African shores of this regional basin appear to be widely unreported.

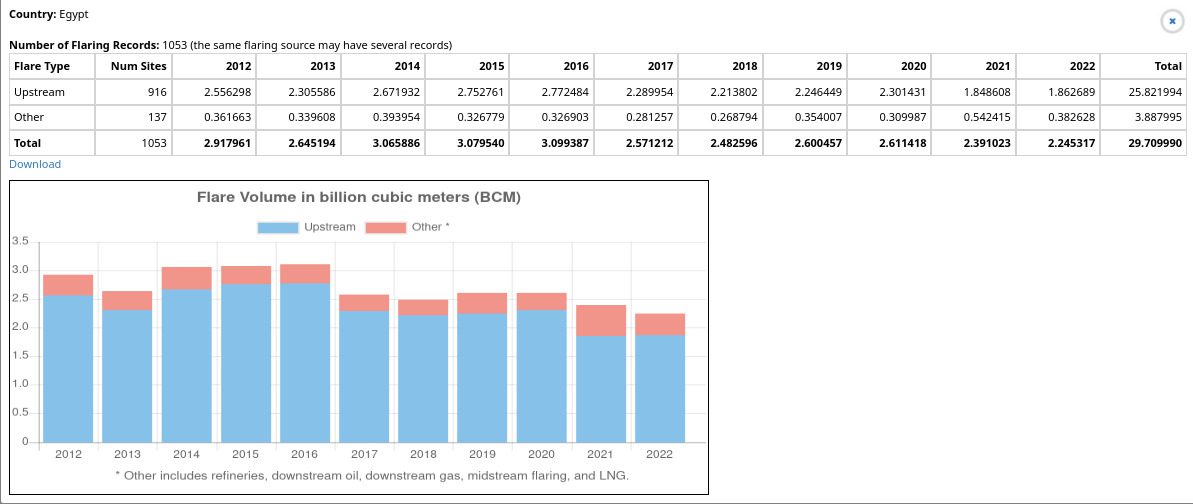

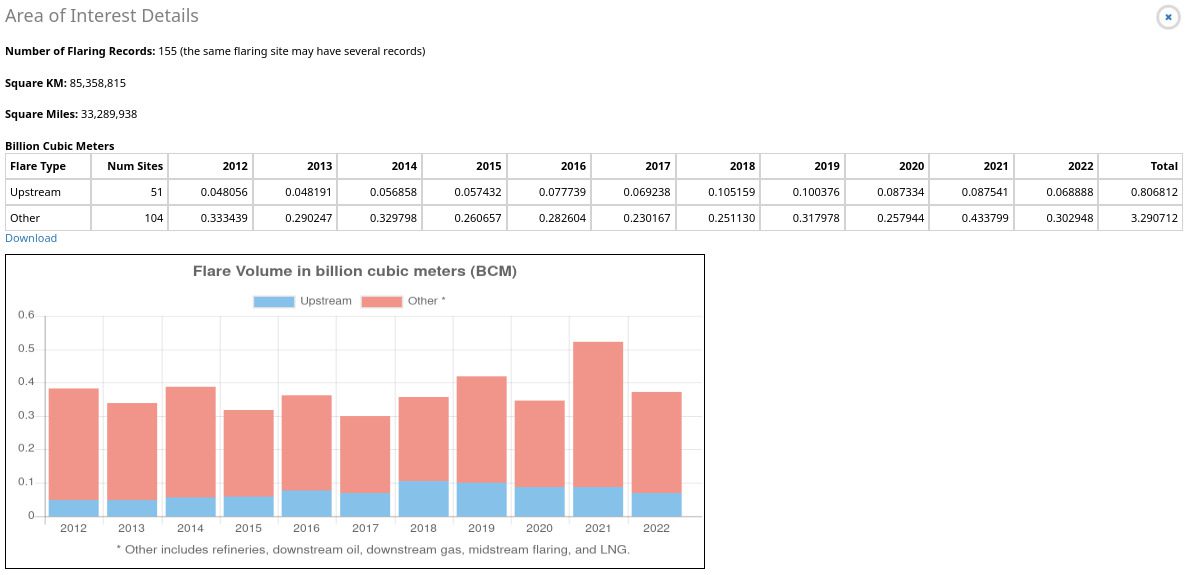

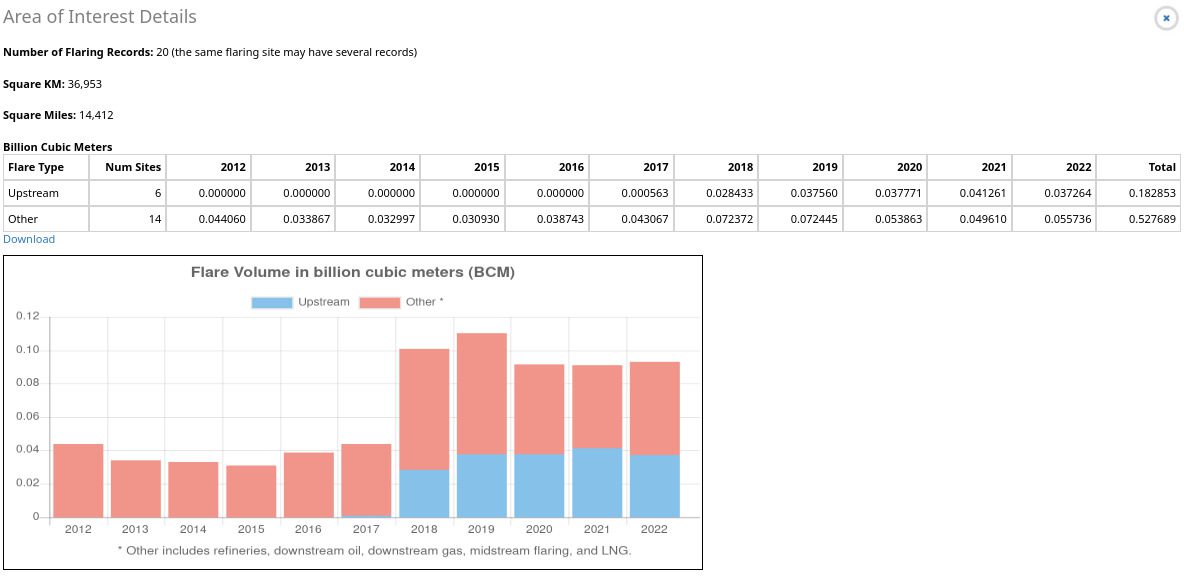

Four billion cubic metres (BCM) – that’s the total estimated volume of gas flared on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast from 2012 to 2022, according to the online resource “Flaring Volume Map” from the US-based organisation Skytruth, which is specialised in satellite imagery analysis. Representing close to 16% of the total of 22 BCM of methane flared over the whole North African side of the Mediterranean seas and shores since 2012.

Their freely available flaring maps allow for detecting flaring sources and quantifying flaring activity, a process which consists of burning unwanted gas due to lack of processing infrastructures – as well as for safety reasons – but a devastating one overall, environmentally speaking.

quantifying flared gas on the egyptian mediterranean coastline (2012-2022) By Alexandre Brutelle (EIF) using Skytruth.org’s “Flaring Volume Map” data

Methane emissions are considered the world’s second source of greenhouse gases after carbon dioxide, representing as far as 25% of today’s global warming according to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). For the International Energy Agency (IEA), close to 40% of these global emissions are attributable to the energy sector – and most notably to the oil and gas industry.

Thanks to satellite imagery analysis, it is now possible to monitor such industry-related flaring activity on a daily basis – and even to backtrack flaring volumes as far as 2012, using data such as the Skytruth’s “Flaring Volume Map”, which is a powerful and valuable tool for environmental monitoring that can be used to run some straightforward analysis on both national and local scales.

Running such nation-wide analysis over Egypt shows a fair reduction of 23% in flaring volume rates for the year 2022 in comparison to 2012, according to the resource.

Results aren’t so bright however when it comes to Egypt’s Mediterranean shore, where flaring levels have remained steady – and actually even doubled for the year 2021 compared to 2017 in some areas, according to Skytruth’s Flaring Volume map.

Some of these maintained flaring sources burning methane are taking place on a protected area near Port El Said, but also within residential districts of Egypt’s second largest city, Alexandria.

Right next to the coast, on the western part of the city’s port, Wadi Al-Qamar’s residential buildings are cornered by industrial zones. Cement and coal processing units, as well as gas and petroleum sites, are a daily burden that everyone seems to be aware of, but flaring feels like a lesser concern.

Wadi Al-Qamar residents unknowingly “affected” by flaring

“The Wadi Al-Qamar region is surrounded by several companies, including petroleum and cement companies. But according to the source, the residents are affected by the cement company, not the petroleum company,” shares Mostafa, a 25 year old local, who concludes: “The petroleum company does not cause us any problems and does not burn any gases, unlike cement companies.”

Another resident from Al-Max district, not far away from the Wadi Al Qamar region, admits not being well informed about actual pollution linked to gas operators in the district , though he has no doubt they must play their own part in the overall alleged bad air quality in Wadi Al-Qamar.

“We have many problems due to the gas company, cement company, and other factories causing significant environmental pollution and getting many people sick. But the suffering of the residents of Wadi El-Qamar is much greater than ours because they are geographically closer to these companies,” the resident shares.

The two districts are well known for being plagued by cement factories, as well as coal factories, dangerously located near residences, which can be easily identified by constant clouds of thick smoke.

These visible toxic smokes, filled with CO2, can be the cause of various respiratory diseases and decreased air quality. Worldwide, cemeteries are responsible for about 8% of carbon dioxide emissions – more than double those from flying or shipping.

A 2019 study led by Rice University has established that flaring can be connected to premature deaths, while the authors remind that the process is known as a “substantial threat to human health,” involving both “dermal” and “respiratory” diseases.

“Residents are also affected by gas,” shares a former city council member who wishes to remain anonymous, “but they are not aware of it.” She also adds that these two districts are well known for their well-documented shares of asthma and chest allergies. Despite being rather visually discrete compared to cement factories, gas flaring units have been proven to have a public health impact up to a radius of at least 60 miles.

When it comes to these two districts, it is within less than a mile from residential homes that 424 millions tons of methane have been flared since 2012, with very marginal reduction, according to Skytruth. Skytruth has also identified these flaring sources to be attributable to various refineries. Contacted over the current situation, both the ministries of environment and petroleum declined to comment the situation on record.

A public agent admitted anonymously that “some gases were burnt” but that it didn’t relate to oil and gas exploration over these districts. It is noteworthy that an official from the Ministry of Environment claimed this practice was in place to “protect the environment,” which is quite an interesting thing to say since flaring has proven to also have impacts beyond those on human health.

Flaring signals over the Ashtum El Gamel natural reserve

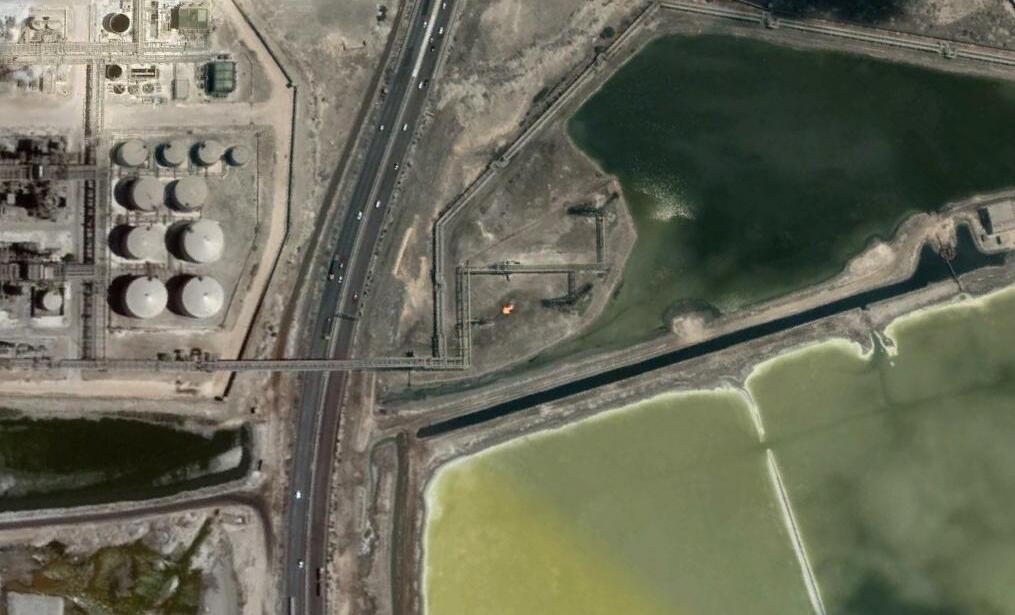

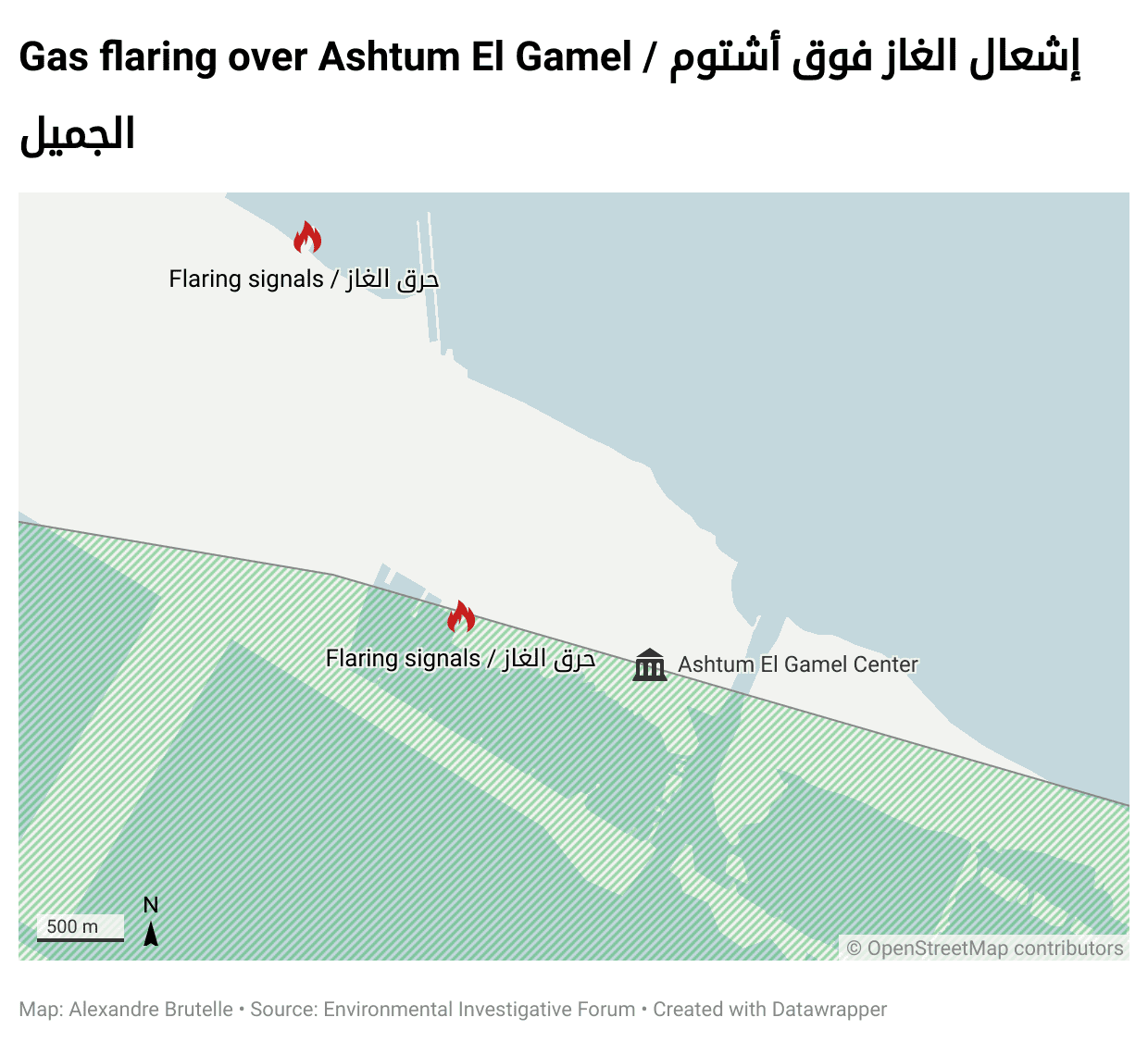

Far more east on the Mediterranean coast, between the cities of Damiette and Port Said, Ashtum El Gamel is the only protected area in the entire governorate and also happens to be Egypt’s largest bird area. It also faces a shore populated by large networks of pipes and various petroleum processing units.

The reserve comprises a wetland called the Almanzal Lake, just about 5 miles away from Port Said’s Airport and minimal residential zones. Contacted for this article, one of the residents, a middle-aged woman, doesn’t believe the reserve to be affected by “any type of pollution linked to oil and gas activity.”

The resident is seemingly unaware of the presence of a flaring source near the reserve: “This is the first time I’m hearing about this despite living in this governorate since birth.” Yet again, while gas flares may be discreet by nature and difficult to access, they easily identifiable from their tracks in the sky.

As it appears to be in this area, two flaring sources are located around the reserve, including one of them only a few hundreds metres away from the reserve centre’s building.

Nefarious effects of flaring go beyond human health hazards: it also impacts soil, vegetation, and water sources. When releasing NO2 (Nitrogen oxides) and SO2 (Sulphur dioxide) in the burning process, flaring provokes acid rains that will eventually pollute the surrounding biosphere, according to the Nigerian Environmental Law and Research Institute. This acidity has a devastating impact on water and soil quality, going against what our governmental source had previously described as environmentally friendly.

“Major opportunity costs of these anthropogenic emissions comprise the rise in sea level, coastal erosion, wildlife extinction, loss of biodiversity, acidified water penetration into coastal aquifer, and other lethal endemic effects of acid rain on the coastal ecosystem,”states a 2022 scientific study on flaring impacts in the Niger Delta.

Within less than a five mile radius, methane releases have almost doubled from 400 million cubic metres in 2012 to over 700 million in 2022, including directly on the site’s official limits and only a few steps away from its managing office connected to the Egyptian Ministry of Environment.

Asked about the current legislation over flaring in protected areas, once again, both the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Petroleum declined to comment on the situation on the record.

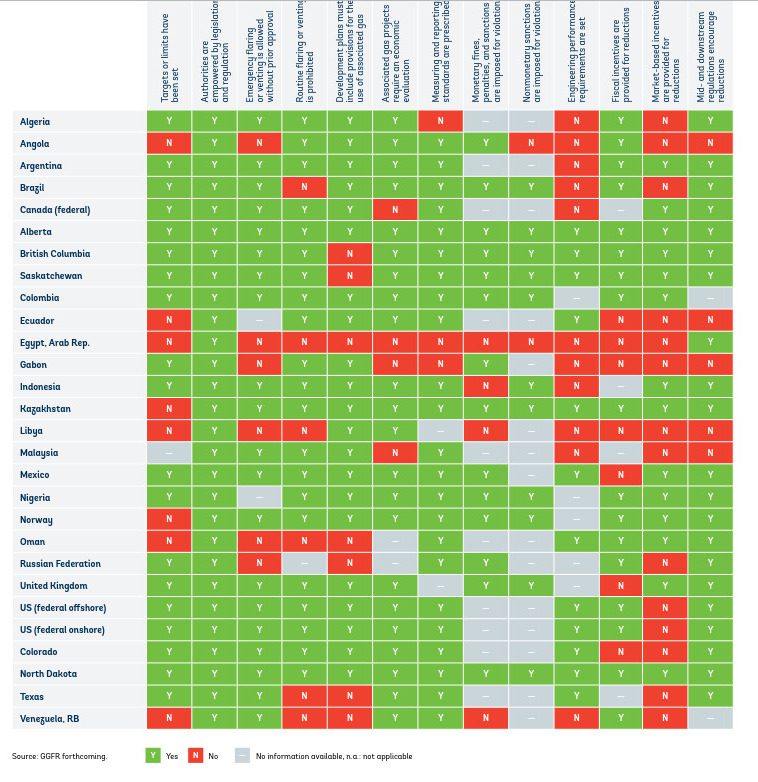

Our governmental source, however, assures that “any flaring that occurs happens within regulatory frameworks.” This is undoubtedly an overly positive statement, in a country that actually does not have any laws regulating flaring.

In other areas of the country’s Mediterranean coastline, such as the Damietta port, flaring rates have skyrocketed and even tripled in comparison with their 2013 rates, according to Skytruth.

The World Bank’s good student in the absence of regulations

On the international scene, Egypt has been featured as a good example of mitigating and reducing routine flaring. Since 2015, the country has been part of the Zero Routine Flaring program (ZRF), a global initiative launched by the World Bank and endorsed by dozens of governments, companies, and development institutions, which aims to end routine flaring by 2030.

“Governments that endorse the initiative will provide a legal, regulatory, investment, and operating environment,” further explains a World Bank text featured on the ZRF’s webpage. But, when it comes to Egypt, a legal and regulatory framework is yet to be developed. To this day, the word “flaring” is not found in any official policy: “Flaring is not used in any textbooks,” comments the governmental source.

Despite the lack of regulations, “Egypt successfully reduced flaring” in 2022 according to a joint report produced by the Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership and the World Bank in 2023. Under which conditions did this take place, though? A separate study from 2022 produced by the same organisations showed that out of all ZRF countries, Egypt was the poorest ranked one in terms of regulatory frameworks on flaring.

If flaring is reduced on a national scale but maintained around residential areas or even greatly increased in some localities, can Egypt’s efforts really be considered a plain success?

Egyptian authorities couldn’t bring any element to our attention that could answer these questions. The World Bank did get back to us on the matter, stating that “comparing regulations across countries is complex as regulations that work in one country’s context may not work equally well in another.” Nevertheless, they do not acknowledge that Egypt actually does not have any specific regulation on the flaring.

Dr. Heba Moutawak, Director of the Media Center at the Ministry of Environment, said his ministry was “not concerned with this issue,” while the Minister of Petroleum and ANRPC (Alexandria National Refine & Petrochemical), who are actually in charge of the management of the flaring units that we have identified in this article, did not answer our requests for comments.

إقرأوا أيضاً: