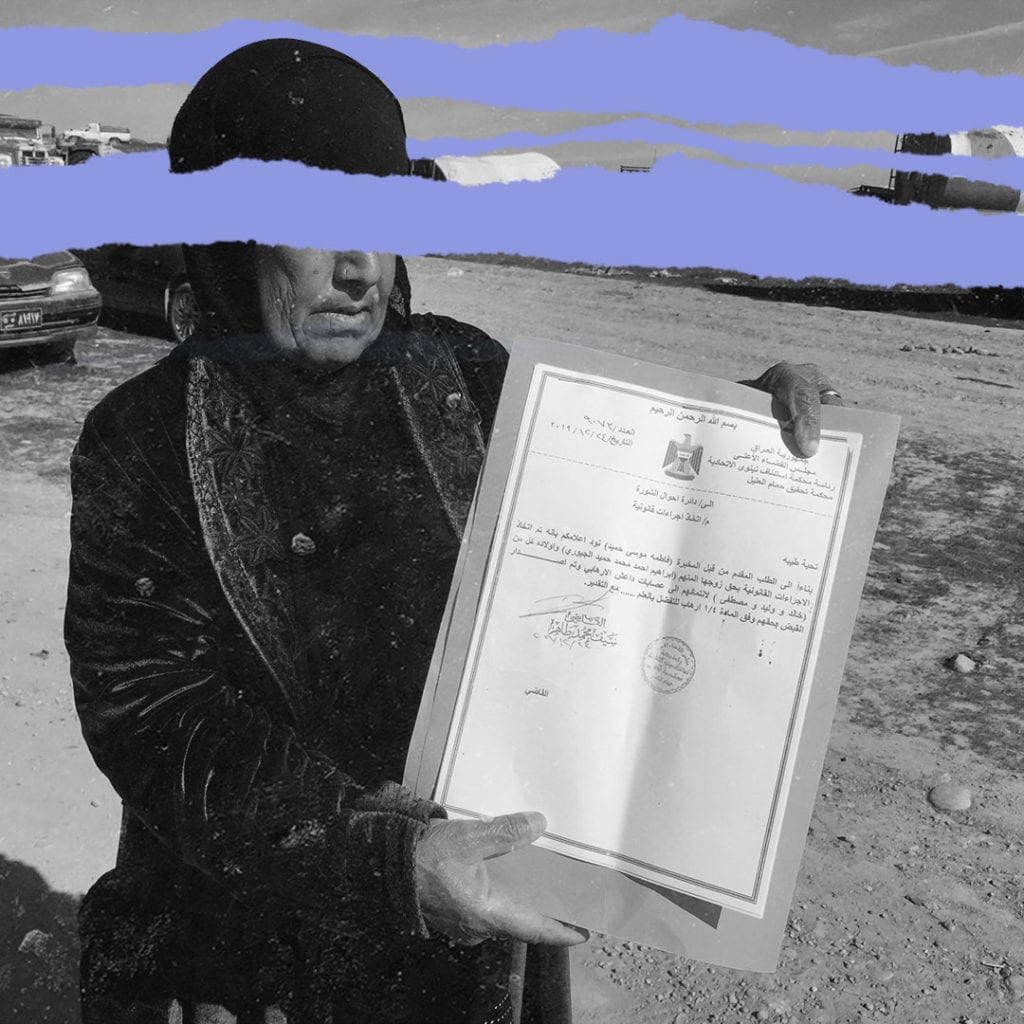

Iraqi widow Fatima Jabouri spends long hours at the gate of the Salamiya camp for displaced people near Mosul, waiting for permission for her and her grandchildren to return her hometown from which she was expelled in 2017, due to the affiliations of her late husband and three sons with the infamous Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

She finds it hard to convince people that her grandchildren are not responsible for what their parents and grandfather did, and that they do not pose any danger.

“I disowned my husband and children, and will do anything for me and my grandchildren to leave this prison,” she says, pointing at the camp’s razor-wire fence and fortified gates through which no one can leave or enter without prior approval.

14,767 families who had one or more members in it that had belonged to “ISIS” were displaced to other areas or gathered in private camps, following the collapse of the organization in 2017.

Fatima’s late husband Ibrahim fought for ISIS. He was killed in an air raid in the 2017 Nineveh liberation war. As for her sons, she knows that the oldest, Khaled, met the same fate as his father, most probably in the 2017 battle over Mosul’s Al Farouq Street, as she has not heard from him since.

Her second son Walid is missing. It has been years she has not had news from him, while her youngest son, Mustafa, has been detained by Iraqi forces. There are thousands of women like Fatima unable to go home. Only a few were forgiven by their communities and allowed to return.

One of them is Um Mohammed, who preferred not to reveal her real name. Her husband is serving a 15-year prison sentence in Al Hout in the southern province of Dhi Qar for joining a terrorist organization. Um Mohammed was able to return to her home in the Al Shoura district, where she was welcomed by her family and neighbors. Today, she just wants to live her life. She says not to care about the people who only show hate for her and her children, because of her husband.

“I’m sure that he what he did was against his will,” she says. “Many people got involved with ISIS in a moment of weakness and despair.” Major Ahmed, from the Tribal Militia, the Sunnite counterpart of the Shiite Popular Mobilization Forces, agrees.

“Um-Muhammad’s husband didn’t adopt a radical ideology,” he says. “He joined ISIS due to poverty. He wanted to protect his children from hunger. The community allowed his family to return because he never raised a weapon against anyone.”

14.767 families

According to official statistics, 14.767 Iraqi families saw one or more members join ISIS in Nineveh, Anbar, Salahuddin and Diyala. Following the liberation of these governorates and the ISIS breakdown in mid-2017, they migrated to other regions in the country or were detained in camps.

In January 2017, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) signed a five-year partnership with the government’s Implementation and Follow-Up Commission for National Reconciliation (IFCNR) to establish a national integrated reconciliation process.

Many families of ISIS fighters, however, have described the $50 million program as “slow and complicated.” The program faces difficulties, as many Iraqis reject its implementation.

According to a statement by the United Nations Development Program, a code of honor was signed in the al-Mahlabiyah area, west of Mosul, on October 14, 2020, requiring the return of 1,100 ISIS families to the district and the surrounding villages (the ones they’d fled from in the past).

International human rights organizations describe the detention of families of women and children in the camps as ‘arbitrary detention’ alongside branding them as “ISIS”.

Arbitrary Arrest

International organizations such as Human Rights Watch describe the detention of women and children in camps, due to the affiliations of their husbands, fathers or brothers as “arbitrary arrests of adults and children.”

International law prohibits arbitrary detention. Any deprivation of liberty must be governed by a law that is “available, understandable, non-retroactive, and applied in a consistent and predictable manner.” People can only be found guilty in a fair trial and should be allowed a judicial review. Any detention that does not meet such basic requirements is illegal and arbitrary. Imposing collective punishment on whole families, communities and villages can furthermore be considered a war crime.

What’s more, under international law children may only be detained as a measure of last resort and for the shortest possible time. If children are detained, the authorities should provide for such things as adequate food, medical care, education, physical exercise, legal assistance and communication with their families. In Iraq none of this is available.

Camp Conditions

In the Nineveh governorate there are fove camps housing ISIS members’ families. Al Jadaa 1, Al Jadaa 5, Hamam al Alil, Jabal Sinjar and Salamiya. They are managed by international organizations in coordination with the guidelines issued by the Iraqi Ministry of Migration.

According to Khaled Abdul-Karim al Obeidi, Head of the Nineveh Immigration and Migrants Department, the camps house some 12,000 families and 59,000 people. They lack health and education facilities, and live in constant fear of being deported, even though many of them have nowhere to go, as the war has destroyed their homes and properties.

Al Obeidi explains that schools in the camps opened by international aid organizations suffer from a shortage of teachers, as is the case in the whole of Nineveh.

Ahmad Subhi al Qaragholi of the Iraq Bridge Relief and Development Organization says his organization has implemented several programs in the camps, including one offering psychological treatment for children.

“There is shortage of supplies,” he says. “But the main problem remains the lack of rehabilitation programs for children and families. Having lived in the camps for three years, most people still don’t know what future lies ahead.”

Numerous organizations cooperate under the UN program aimed at rehabilitation and reintegration. Yet, while some areas near Mosul, such as Bashiqa and Al Mahalabiya, have welcomed people back, others such as Al Shurah and Al Qayara rejected them.

Disownment is not Enough

In an attempt to address the conditions of thousands of displaced families whose children belonged to “ISIS”, the government adopted a concept of “acquittal”, by examining the conditions of all members of these families before allowing them to return to their areas. Sheikh Maysar al-Hasoud al-Dulaimi, one of the sheikhs of Nineveh Governorate, sets conditions for the return of the families of the organization’s members to the areas where his clan is concentrated in the south of Nineveh. In the event that this happens, the returnees are forced to undergo a qualification course in the field of combating extremist ideology and provide proof that they have obtained a certificate from an organization specialized in this field confirming that their extremist ideology has disappeared.

However, the concept of disownment is rejected by many of the tribes in various parts of Nineveh, due to the conflicting concept of revenge. Sheikh Maysar al-Hasoud al Dulaimi explains the conditions under which ISIS families can return to the tribal area in the south of Nineveh under his control. “These families must promise to pay blood money for the tribe’s sons killed by ISIS,” he says. “The tribes are currently establishing the minimum values. In addition, returnees are obliged to attend a rehabilitation course and must provide a certificate from an organization specialized in that field.”

A judge working in a court specialized in terrorism cases, who preferred not to be named, claims that disownment has no legitimate basis in Iraqi law. “Rather, it is a practice adopted by the judiciary in dealing with families whose sons joined ISIS,” he says. “Continuing to isolate families may have grave consequences. As time passes, they will bear a growing grudge towards society, which may push them to think of revenge in the future, which could trigger yet another vicious circle of violence.”

Abu Yahya al-Hatim, representative of the southern Mosul tribes in the Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC), agrees and emphasizes that isolating people in camps is destructive and may have grave consequences in the future. He calls upon the Iraqi government to take its responsibility and coordinate with tribal chiefs and district leaders, who refuse families to return, to come to an agreement to guarantee their safety and the safety of the region as a whole.

“There is a huge gap between children who grow up in a tolerant society that consider them a part of it and those who grow up in isolation, who cannot help but thinking of revenge,” he says. “These families were once part of the community yet have become unwelcome, which affects the country’s social cohesion, especially as we are talking about tens of thousands of people, not just a few hundred,” says sociology professor Hazem al Zubeidi. “Research shows for example that many people are reluctant to marry into families linked to ISIS.”

“We Do Not Want Them Among Us”

A Human Rights Watch report in August 2019 showed that local authorities in Nineveh expelled over 2,000 Iraqis from displacement camps. Some had no other choice than to return to their hometowns, despite concerns for their safety. Several people had stun grenades hurled at their homes. In September 2019, Minister of Migration and Displacement Nawfal Baha Mousa announced the closure of four Nineveh camps, namely: Al Jada 2, Al Jada 3, Mudarj, and Salamiyah 3, and the return of the displaced to their hometowns, which included many families of former ISIS fighters.

The reactions of families who fell victim to ISIS show just how deeply rooted the problem is. Hussam al Din who lives in Mosul’s Qayyarah region believes his orphaned relatives are not willing to live with the families of the men who killed their parents. Worse, many of them may want to take revenge on anyone with links to ISIS. The 47-year-old lists the names of his relatives who have been killed by ISIS bullets. He pauses at 12.

“Eight of them were with the local police in Nineveh, three in the army, and one in the federal police,” he says. “They were doing their duty to protect the country and provide for their families.” Ghania Hamid, from the Shura district south of Mosul, has lost her son Saad. He was a lieutenant killed by ISIS fighters in an armed assault on Mosul in May 2013. She refuses any form of reconciliation with ISIS fighters’ families. “Whoever calls for the return of ISIS wives and children to our region has never tasted the bitterness of losing a loved one, and knows nothing about a son becoming a martyr in the prime of his life,” she says.

In the Hammam al Alil area south of Mosul, Ghassan Abdul-Ghani did not rule out the possibility that ISIS uses the families to hide fighters. The 57-year-old farmer suggests the families should be settled in remote places, where their movements should be monitored until it is absolutely certain they no longer pose a threat. “There is hardly a family in southern Mosul that has not lost one or more of its members to ISIS terrorists,” he says. “Consequently, we do not want their families among us.”

ISIS Language

Anyone visiting a displacement camp with ISIS families will hear words and expressions, such as Islamic State, Caliph, the soldiers of the Caliphate, jihad, and many other phrases, that indicate a loyalty to ISIS.

According to civil rights activist Jamal Abdallah, however, this is mainly due to the desire of these families to voice their resentment over the way they are treated and the harsh living conditions they are facing. He believes that many families still uphold the lexicon ISIS used in the regions under its control. Jamal points out that a boy who was five when entering the camp in 2017 is now eight, and all he has heard from his angry mother or sister about the outside world is the hope that one day it will return to the true faith. This may lead to feelings of resentment and revenge in the years to come.

Despite the government’s assertion that it wishes to close the camps and see the displaced return home, despite its promise to address this issue in a just and secure manner, the facts on the ground tell a different story. Dozens of statements by officials and testimonies by ISIS families and its victims also reveal that the government has so far failed to develop an integrated strategy.

Ihsan Al-Shammari, head of the Center for Political Thought, believes that former Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi should be blamed for ignoring the national reconciliation committees formed by his predecessor Haider al Abadi in cooperation with the UN. According to him, these committees took almost all problems into account and were more down to earth in their approach. They held prolonged meetings on the issues and developed a strategy in cooperation with clerics and the authorities to rehabilitate these families.

“If the Abdul-Mahdi government had implemented the social reconciliation program, we would have seen a totally different situation today,” he says. “And we would have been able to resolve many of the tribal issues which continue to pose a challenge for the return of thousands of families. It is a very disturbing issue and turning a blind eye poses a serious threat to the country’s security.”

* The investigation was completed with the support of the Nirij Investigative Foundation.