After losing custody of her children following her divorce, she visited this fence for years in hopes of stealing of few glances of them. She says “I spent my life watching them from afar” as she stares at the empty playground that has been deserted due to Corona Virus protection measures and bans.

Badiya Fahs (50 years old), is a Lebanese writer and Journalist who has been fighting a fruitless custody battle for the past 12 years. She has 5 children; 3 boys and 2 girls, from two marriages that have ended in divorce. Although her older children are with her, the issue lies in her second divorce and thus, her youngest two children. “My children were taken away from me in the eye of the storm” Badiya says bitterly as she talks about the unjust laws and the societal culture that practices extreme discrimination against women, a type of discrimination she paid a hefty price for. Although only a few kilometers away, she has become an invisible and unknown character in their lives; unable to make contact with them, all she can do is watch from afar. “In order to see my children, I tried really hard to reach a peaceful agreement with my divorcee. I tried to depend on myself and try to remain close to them, but to my despair, here I am 12 years later, just watching them from a distance.”

Divorce and the right to custody are not rulings that she can easily obtain whenever she wants. Badiya is a Lebanese Shiite Muslim and the laws of the Ja`fari personal status courts apply to her. According to these courts, divorce is a decision by the husband. The Shiite Personal Status Law does not recognize a woman-led separation, and there is no way for a woman to file for a divorce case and obtain her separation. Rather, she must file a request for a “ruler’s divorce” before a Ja’fari religious authority, a process that could take years. As for custody, it is automatically acquired by the father after the male child reaches the age of two years, which is the cause of great suffering to Badiya and the many women whose stories we witness in the media and courts every day.

These legal criteria for custody rights completely overturned Badiya’s life. Her husband only agreed to divorce after she relinquished her dowry, but custody of the two children was automatically his right, Badiya says: “The man’s right to custody is assigned at his birth, he does not need to fight for it. He has the support of his family, his society and his socio-political and religious environment. That’s how privilege works. The woman is the one who needs to go to court, take a specified custody period and file a custody case. I didn’t file a case, because I knew where it was headed”.

Badiya comes from a religious family, daughter of the late Hani Fahs, a theologian characterized by his moderate ideology. A figure known for its commitment to a wave of Shiism that is independent of the political and religious sectarism in Lebanon, and in the same vain, independent of the Ja`fari personal status courts. All of which are under the control of the Amal Movement and Hezbollah, the two most powerful and influential sects in the Lebanese Shiite community.

Many factors weakened Badiya, caused her to avoid a legal battle and led her to believe that she would inevitably fail. “I have not filed a custody lawsuit nor am I proceeding to prove my right to custody. I don’t think I could beat them. At the time, my specific political circumstance was held against me … I don’t fit the norm, because I am from a family that does not agree with the sect’s politics. We were being punished for having different political and religious views. all the circumstances were against me and it spilled into my case.”

After losing custody of her two children, and over a period of 12 years, Badiya established a social network of teachers and friends who convey her children’s news to her. She also insisted on living in Nabatiyeh to be close to them and keep an eye on them from afar. On her phone, she keeps pictures of them that she took for years at school celebrations. She would participate as a teacher or guest, and would sometimes wear a costume in order to blend in, “I wove a network of relationships with people close to them … I was able to know how they are doing, their grades at school, who their friends are… I knew all their news, even when they got sick or went out. So, if they were at a restaurant I would be in a corner, keeping an eye on them.”

Our Experience with Divorce

Her first marriage was when she was 16, in a country whose laws don’t specify a minimum age for marriage. According to Islamic Sharia, almost all Islamic sects can contract the marriage of girls starting from ages 9-12.

Badiya says: “I come from a religious environment and a religious family, and it is a natural thing in these types of families to prepare immediately for marriage. I mean, at the age of 16 when I got married, all the daughters of the sheikhs of my generation were either married, about to get married, or had a groom on the horizon. I had to fit the norm”.

Lebanon Legalizes Underage Marriage

The study “Early Marriage of Girls: Violating Childhood and the Propagation of Poverty” prepared in 2015 by the professor and social researcher Zuhair Hatab, in cooperation with the Lebanese Democratic Women’s Gathering, shows that more than 90 percent of underage marriage cases took place with “complete ease” and “simple procedures” in Lebanon’s Sharia courts. In his study, Hatab refers to the “prolonged silence of religious institutions towards the marriage of minors,” indicating that early marriage reflects the extent of the spread of this socio-ideological culture and its religious dimensions among people, “Under this culture, men prefer to choose partners with characteristics that facilitate the extension of their authority in the name of religion.”

This is what precisely happened with Badiya, her early marriage was a familiarity in an environment that normalized the matter. Her marriage did not last more than 7 years, during which she gave birth to three children. “I was 23 years old. I was the first one to get divorced in the family, and it was unacceptable to many… It was 1993 and I was the first single mother in the area who lived alone with her children, had reached a custody agreement with their father, rented a house, and worked.”

In order to support her three children, Badiya worked as an Arabic language teacher and then in journalism. Only to go back and marry again, trying to escape from the difficult life of a divorced woman in a traditional society. “My second marriage’s circumstances are like the marriage conditions of any young divorcee living alone; a young man liked her.” But the second marriage did not last long, “I was pregnant with my second son when I discovered that my husband had gotten married, he had left the house because he couldn’t live with me anymore, and so he found a bride and married her. He didn’t want to divorce me because he would have to pay my 50-thousand-dollar dowry. I kept waiting and then after a year, I had had enough and filed for divorce myself. By then I was 38, and I had relinquished all my rights.”

No Equality … No Protection

Lebanese women and men are subject to 15 religious courts each for different sects, as there is no unified civil law that regulates personal status. This judicial pluralism has roots that go back to the Ottoman and the French Mandate periods, meaning that the lives and choices of individuals, especially women, are subject to legislation dating back more than a hundred years back.

The multiplicity of personal status laws and the mechanisms of their application by sectarian courts have been established in violation of the principle of equality between women and men in issues of marriage, divorce, custody and inheritance.

Because of these laws, women from different sects face legal and social obstacles when trying to end underaged, failed or abusive marriages, they face restrictions on their economic rights, and they must deal with the hardships of custody battles and the possibility of losing custody of their children if they remarry.

Literature and praxis both show that all Islamic and Christian courts are discriminatory against women. Insofar as they enforce an ‘ideal of obedience’ and ‘rules against disobedience’, which apply to women in the event that they fail to submit to their husbands and decide to take action that “dislocates the institution of the marriage”. Even though some say that such rationales aren’t truly used in praxis, they stand corrected as we see them in entrenched in both legal texts and used by many in legal battles.

Dar Al Fatwa is My Daughters’ Legal Guardian

Sarah (a pseudonym) was living in Beirut. With a financially and emotionally stable life, she was married, had two daughters and worked in a small investment project with her husband. In 2017 her life was completely turned over after her husband’s sudden death from a heart attack, leaving her with their two girls aged 7 and 13.

Sarah (39 years) found herself stripped of her responsibility for her two daughters. In Lebanon, women face religious laws that reinforce the position of men at the expense of women, especially with regard to the uneven distribution of inheritance in Muslim sects. According to the Sunni sect to which Sarah belongs, the restriction of the inheritance is linked to the presence of the male child only and a non-heir (i.e. herself) can only obtain up to a third of the assets.

Sarah’s husband did not have male brothers, so the inheritance belongs to her two daughters, but according to the laws of the Sunni courts, the mother cannot be a guardian of her daughter’s money. “When I tried to open a bank account for them, I could not. They told me I have to get permission from Dar Al Fatwa and every time I want to withdraw money, I had to do the same thing…. As a woman, I couldn’t be their legal guardian. Dar Al Fatwa is my daughters’ legal guardian.”

I am a working, independent woman, but here the situation has been flipped on it’s head.

She avoids going to Dar Al Fatwa and delegates the matter to her lawyer in order to avoid provocative situations and flashbacks of sheikhs trying to justify not granting her guardianship over her daughters. She will never forget how they would narrate stories of mothers who have re-married and forfeited the rights for their children, insinuating that women are incompetent guardians until proven otherwise.

A Country of Sects

The Lebanese constitution considers the country’s political system as a democratic parliamentary system, characterized by a sectarian infrastructure that was established more than a century ago. Upon the annexation and sorting of what was then known as Greater Lebanon and its independence in 1943, the Lebanese people were recognized as a group of sects, with power and positions distributed on this basis.

In the domain of personal status law, the legislator and the civil judiciary decided to distance themselves, leaving matters in the hands of religious courts and their political frameworks. This resulted in the disharmony between legislation and human rights standards and frameworks; all under the pretext of preserving the privileges and rights of sectarian groups.

140/149

Lebanon ranks 140th out of 149 countries in the Global Gender Gap Report.

Personal status laws treat women as second-class citizens with a duty of submission and obedience, while men are given the authority to discipline and have guardianship. For sectarian reasons, a Lebanese mother is still not allowed to pass on her nationality to her children in fear of tipping the demographic balance between Muslims and Christians, a rationale that politicians and officials have not been reluctant to publicize on countless occasions. These experiences have shown the ability of sects to obstruct and hinder the development of legislation on women’s issues. One of the most prominent examples is the Law on the Protection of Women and Family members from Domestic Violence, known as Law 293, which was passed in 2014 after amending essential matters including the refusal to criminalize marital rape and granting priority to personal status laws when there is any conflict-of-issue with the Lebanese constitution . Thus, maintaining the power of discriminatory personal status laws in the face of any attempts to develop legislation towards equality and justice. These complications are not abstract, they place an enormous burden on the lives of women and violate their most basic human rights.

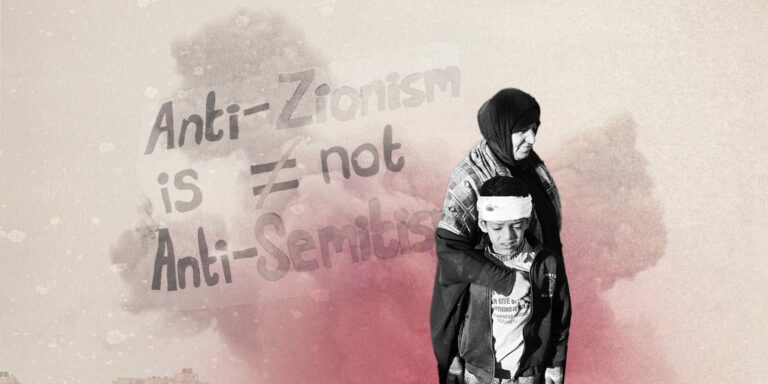

“In the October 17 Revolution … I Saw My Son”

Perhaps, not surprisingly, Lebanon ranked 140th out of 149 countries in the Global Gender Gap Report issued by the World Economic Forum 2018; a report that measures gender parity in the fields of economy, education, health and politics. In its 128 seats, the Lebanese parliament includes only 6 women, representation of women has fallen below the required level in basic sectors of the labor market, such as science, technology and engineering. Despite the vitality of the Lebanese feminist movement preceding Lebanese independence, the issue was treated with great suspicion and women’s rights were recognized by granting slow, gradual reforms that envelop the problems without real change.

After many years of lingering grievances, women have countless reasons to take to the streets. The October 17 uprising witnessed a feminist wave of presence, demands, and slogans in the streets. Women raised their voices demanding justice, equality, and the curbing of legal discrimination against them.

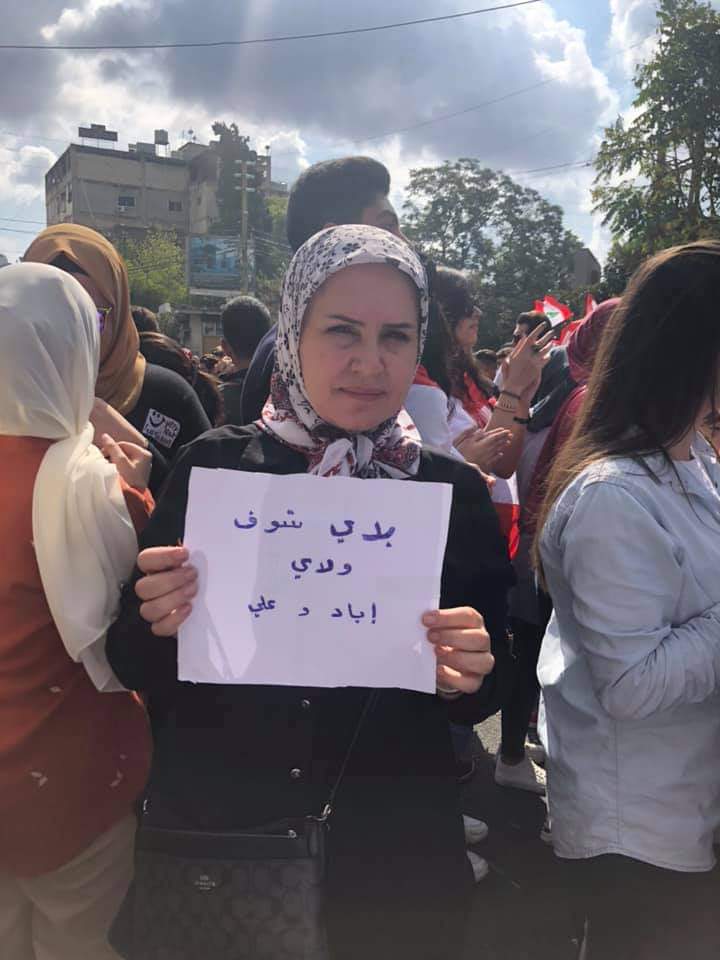

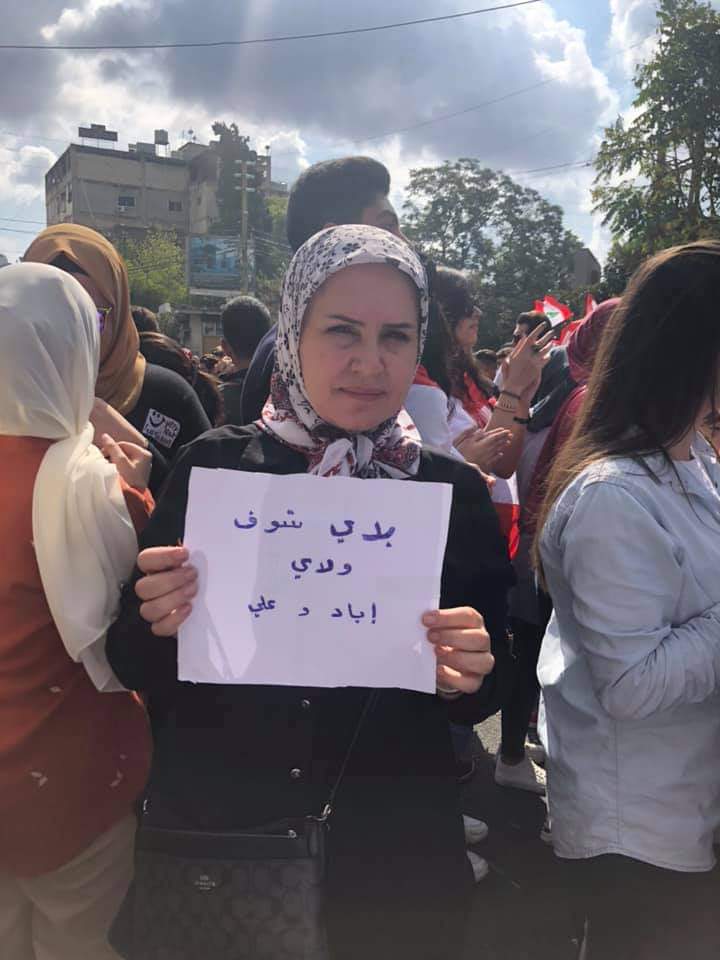

When Badiya saw the flooding of the Lebanese into the streets and feminist presence in the demonstrations, she felt a tremendous energy. In home in the city of Nabatiyeh, two days after the start of the uprising, she drafted a paper on which she wrote “I want to see my children” and went to the demonstration in the city square. She found support and sympathy from women, youth and the protesters who knew her story and helped her find her son in the demonstration. “I said, given that our reality has become a revolution, and people have come down to demand their rights, I want to go down to demand my rights. I was not planning, nor did I know, that my son could be in the same square, then suddenly I discovered that he was there. Some youth took me to him, I asked him: “do you know who I am?”, he said: “yes”, I asked if I could kiss him, he said: “later, not now, I don’t know when…” I couldn’t believe that life had given me this opportunity to meet him, it was the first time I heard my son’s voice.”

An indescribable happiness overwhelmed Badiya when she was introduced to her son as ‘his mother’, not as a random passerby. Many months have passed since that moment, and it was followed by the emotional complications related to what seemed to be a mother, who suddenly and publicly, appeared out of thin air. Who as far as they are concerned, had died or left without looking back. “My eldest resents me, and my youngest doesn’t even recognize me. I cannot just go up to him and say I am his mother. I’ve been invisible for years; I don’t even know what they have imagined about me”. She lived in months wavering between hope and frustration after her communication with her two sons faltered.

Unfortunately, the tide of life swept her away from Lebanon. A country riddled with one of the worst financial and political crises in its history, her work in the National Media Agency became worthless, and thus, Badiya decided to travel temporarily to the Gulf where she could work and live with her eldest daughter from her first marriage. ” Financially, I am obliged to leave the country. like any other human being who had a certain standard of living and suddenly witnessed their income erode in the face of the dollar.”

Badiya left Lebanon for months, perhaps a few years. She left her home in Nabatiyeh, a place adorned with all the memorabilia from her sons’ childhood; She had plastered the walls with their pictures and filled the rooms with their things. Hoping that one day they would reunite. “In their absence, we tried to conserve the things that reminded us of them, so we feel their presence amongst us. Their small toys, their little car chairs, their clothes are still hung in the closets, all the things they liked. Their sisters and I insisted on seeing their things, day in and day out, so we feel like they are still a part of our lives…”

Badiya left Lebanon after unjust laws, cultural tyranny and economic conditions stood in her way. With all the progress that humanity has accomplished, religious, legal and political systems are still mobilizing and uniting to deny women their most basic rights. Much like Badiya, many mothers have lost guardianship of their children and left with nothing more that figments of their past, to hold dear.