This investigation was carried out with the support of the Skeyes Center for the Defense of Media and Cultural Freedom.

Asma Kahil used to live in the al-Sellum neighborhood in south Beirut. Yet, this year she decided to move to the village of Younine in the Bekaa Valley. Why? The Ghadir River.

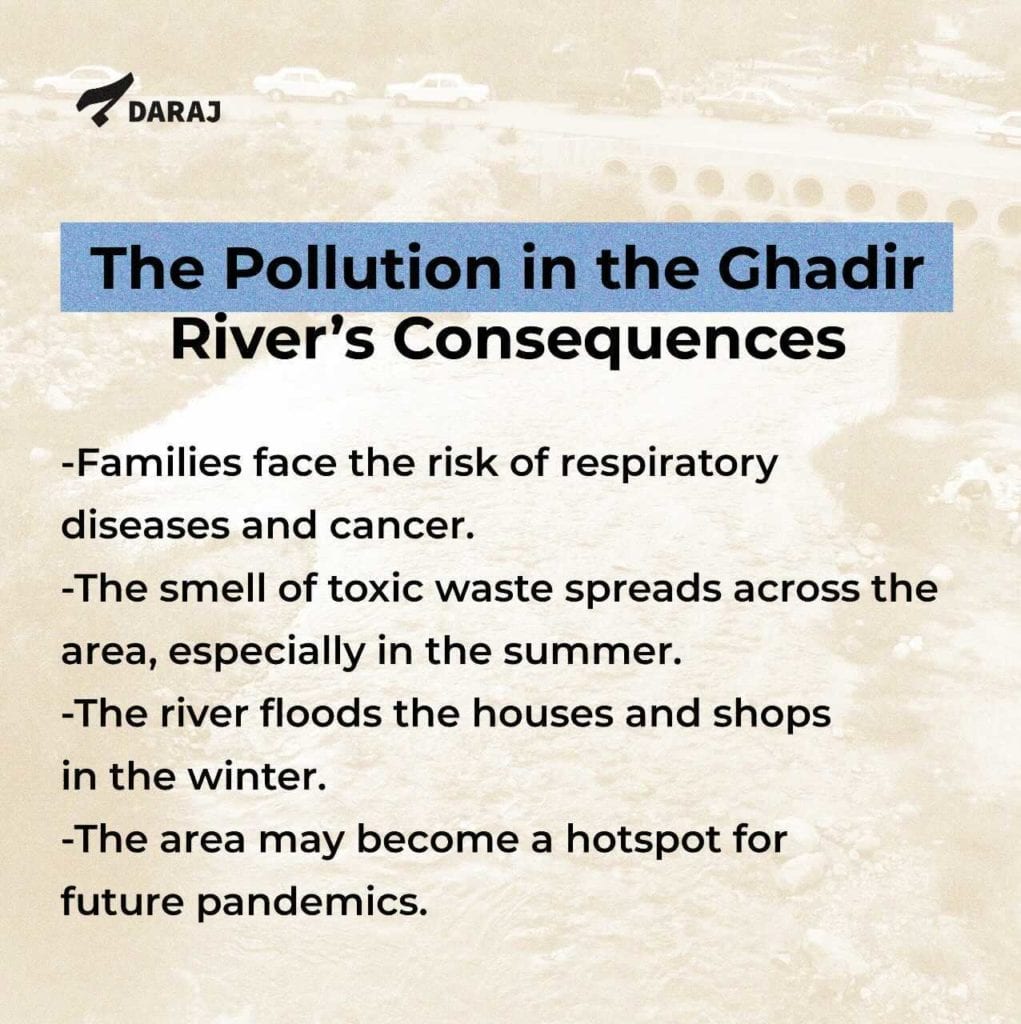

“One day I came back from homeschool, and found the house flooded with water and garbage,” said the woman in her mid-twenties. “I had to stay at my grandfather’s before being able to return to her home. In summer, the stench is unbearable. And there are rats and cockroaches everywhere.”

One of Lebanon’s smallest waterways, the Ghadir River is also the country’s most polluted. Formed by seasonal streams in the Chouf Mountains it reaches the Mediterranean Sea near the Beirut international airport. While the river often floods following the winter rains, in summer the dry river bed remains.

Naturally, it was not always like that. Until the 1950s, the Ghadir River brought life to a varied agricultural landscape, while locals used to enjoy an evening walk along its shores. It was the rapid and uncontrolled urbanization of Dahieh, Beirut’s southern suburbs, that turned the river into the open sewer it is today.

“Our area is total rubbish,” said Fadwa Awad. “Our children are getting sick. My son was only eight months old when he was infected by a virus from the water. He stayed in intensive care for a month and almost died, as his kidney and liver got affected and his hemoglobin level dropped to five.”

Living along the Ghadir River is not only unhealthy, it is also increasingly unsafe. “The annual flooding has weakened the foundations of our building,” said Kahil. “We are afraid that one day it may collapse.” Adding: “Anyone who lives here wants to leave.”

Over the years the miserable Ghadir River has attracted numerous projects and funds attempting to improve water quality, waste treatment and living conditions. As early as 2001, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) announced the $22 million Al-Ghadir Wastewater Collection and Treatment Project, which was to establish three networks for wastewater collection and disposal.

In 2006, Germany launched the €16 million Ghadir Water Project. Yet, one quick look at the state of the river at al-Sellum neighborhood suffices to realize that plans and projects have so far brought little to no relief.

146.5 million euro

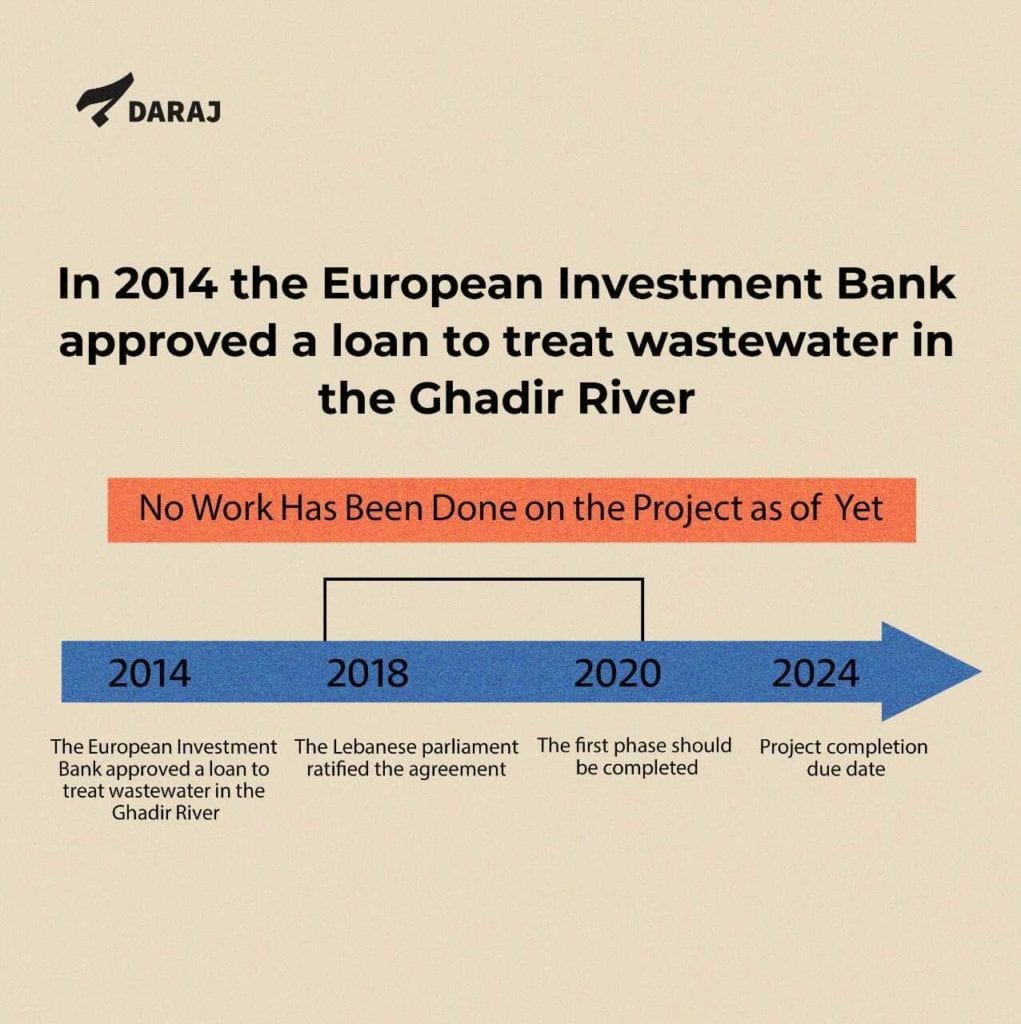

In 2014 the European Investment Bank (EIB) in partnership with the IDB launched what is arguably the most ambitious plan yet to clean the river and improve life alongside it.

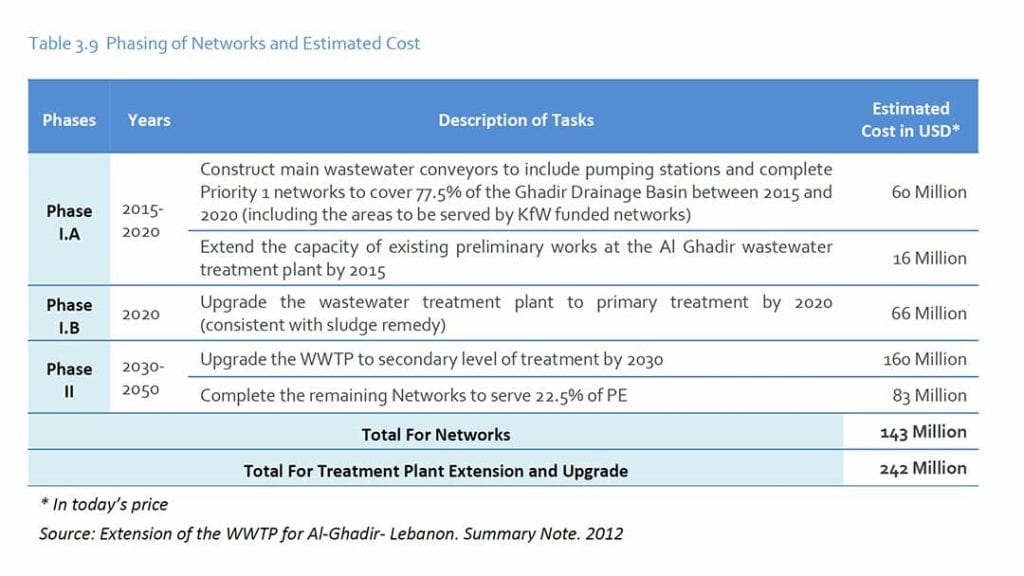

With a total cost of 146.5 million euro, the project foresees first of all in rehabilitating and extending the existing Al Ghadir wastewater treatment plant, which currently only has a rudimentary capacity of 50,000 cubic meter a day, while studies indicate the Ghadir drainage area generates some 700 to 1000 tons of solid waste a day. Secondly, the project intends to construct a sewerage system with a length of some 308 kilometers connecting 19,000 households.

According to the EIB, improved sanitation will increase the quality of life of up to one million people in the greater Beirut area, reduce pollution and environmental hazards in the Ghadir drainage area and, consequently, enhance water quality along the entire Mediterranean coast.

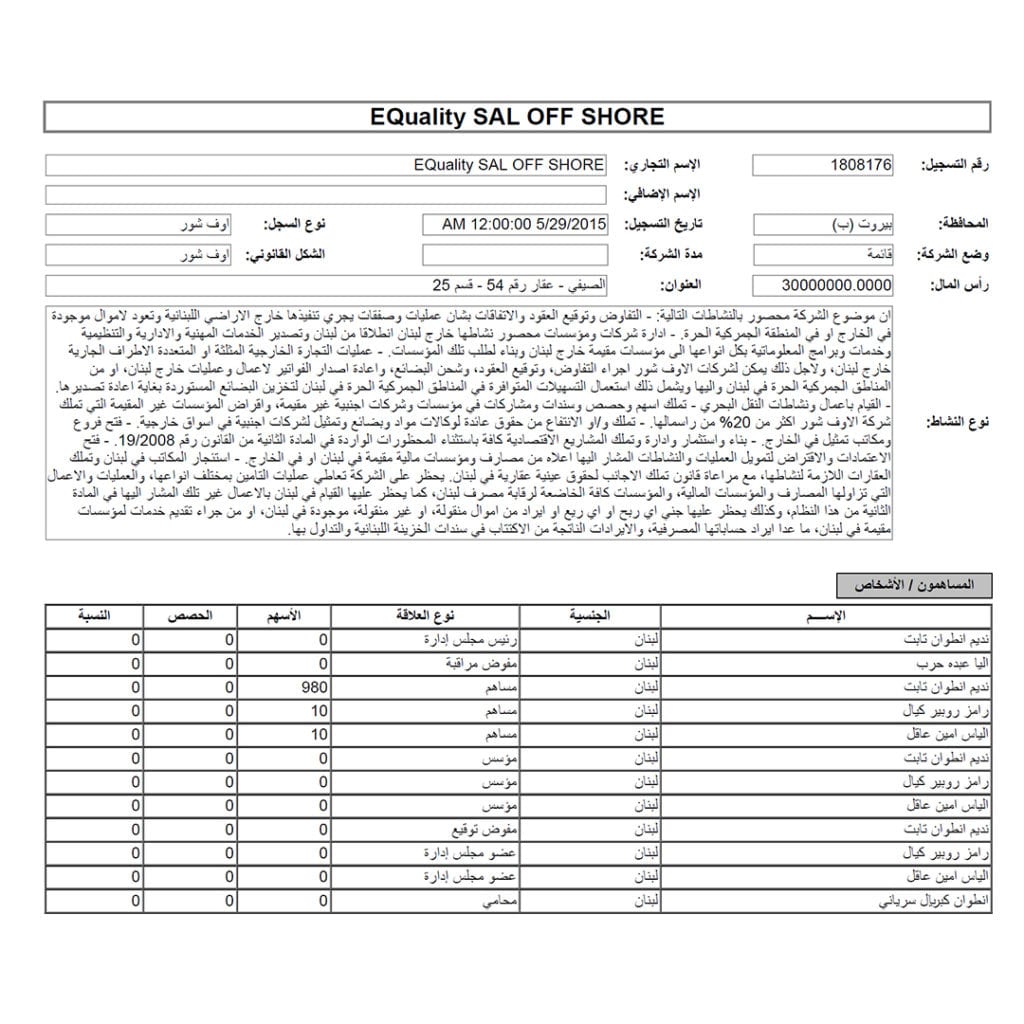

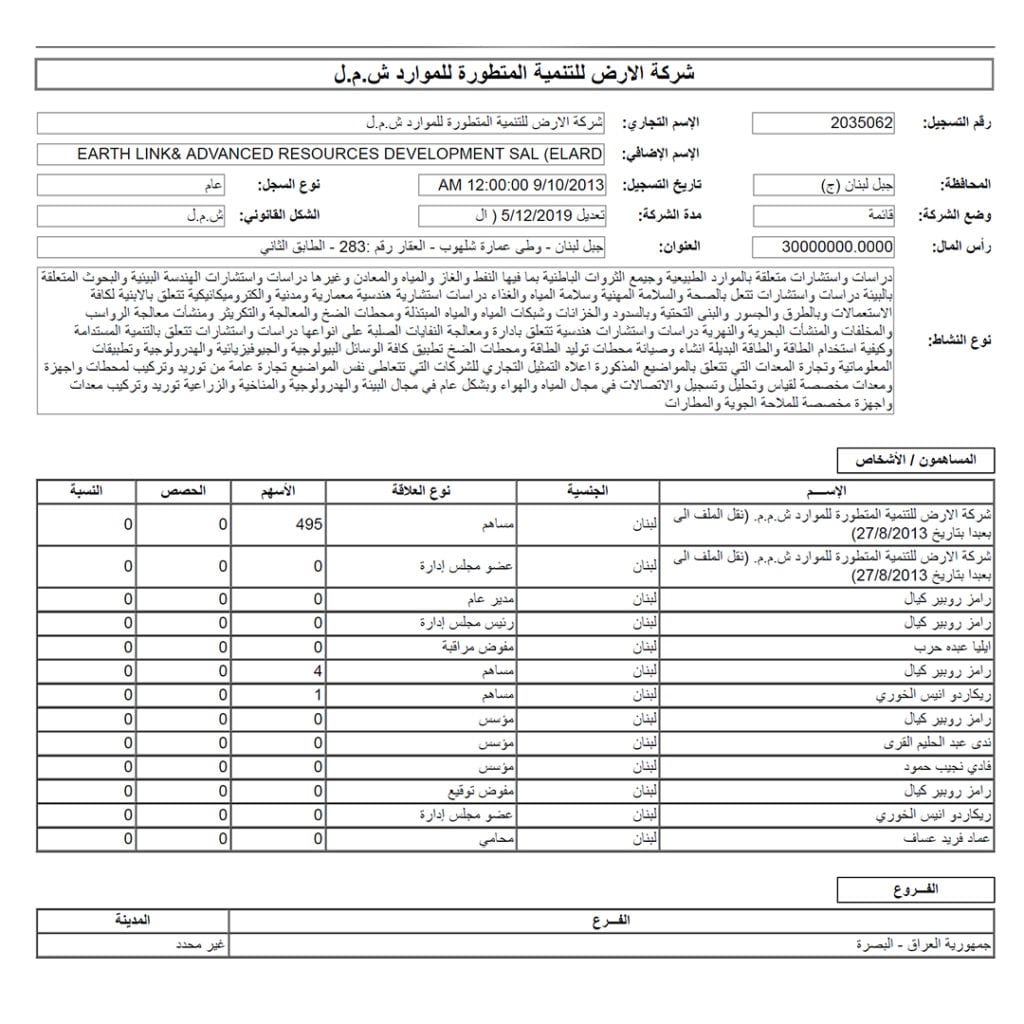

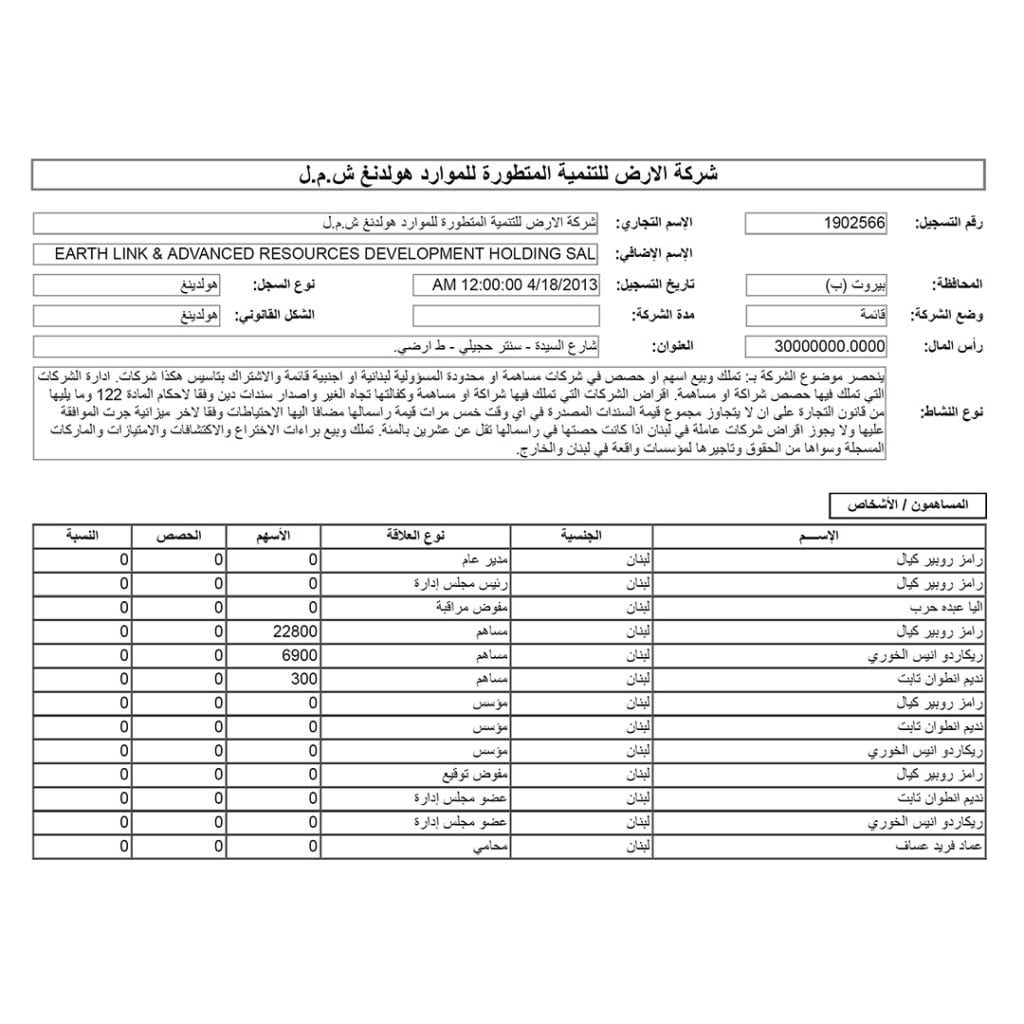

The project will be financed by a 68.5 million euro EIB loan and a 69.7 million euro IDB loan, while the remaining 8.3 million euro will come out of the coffers of the Lebanese state. While the IDB component is meant to develop the existing wastewater treatment plant, which was built in 1998 at a cost of some €7.5 million, the EIB component focuses on building the sewerage system and household connections. In 2012, financed by the EU, a social and environmental study was completed by 3 international consultancy firms (WS Atkins, LDK and Pescares Italia) in cooperation with two local partners Earth Link and Advanced Resources Development Company. Their report numbered almost 300 pages.

Two years later, in 2014, the EIB approved the loan for the Ghadir River project, while in 2016 the IDB loan was approved and in 2018 the Lebanese parliament ratified the loan agreements. In 2020, the first phase of the project should have been completed and in 2024 the entire project is scheduled to be finalized.

Yet, today, almost 10 years after the first study, 8 years after signing the EIB loan and 4 years after ratification, the people in al-Sellum are still waiting for the first stone to be laid. Which makes one wonder: what has been done? Where are the millions? Will this project ever make a difference or will it be just be added to Lebanon’s ever-growing file of good intentions and wishful thinking?

EIB

“It is not uncommon for projects like Al Ghadir to incur comparable delays between loan approval and signature. ,” an EIB spokesperson told Daraj. “The main reasons [behind the delay] include: 1) the time lag between loan approval and signature mentioned above; 2) time needed for Parliamentary ratification of EIB and IsDB loans.”

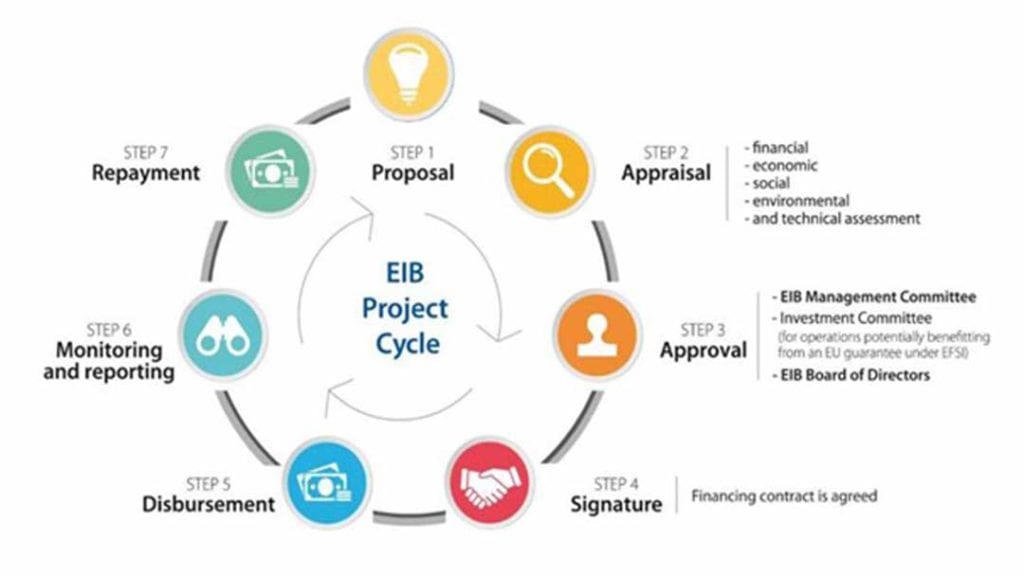

He furthermore stressed that any EIB-financed project goes through 7 stages to comply with EIB and EU standards: Yet, due to early delays all these have been postponed.

He expected work on the ground to begin by the middle of next year, yet immediately added that: “current circumstances of political and economic uncertainty, coupled with the COVID pandemic, make it extremely challenging to make any exact predictions.”

CDR

Walid Safi, government commissioner to the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) emphasized that none of the funds had been received yet. “The CDR is only a mediator and does not receive any money from the loans,” he said.

“The funds remain with the financier until the companies implementing the project are identified.”

According to him, the CDR is still in the phase of selecting consultants that will conduct two more detailed studies, which will form the basis for the tender on which construction companies can eventually bid.

The studies will take around 6 months to complete, after which it will take at least another 6 months to select the companies that will implement the project’s two components. In early June, Safi told Daraj that the consultants were likely to be identified by the end of June and that the actual work on the project might start by the middle of next year. By the time this report was published, however, there had been no news of any confirmed consultants yet.

According to Safi, the site for the wastewater treatment station has been secured, yet part of the area was confiscated by a decree of the Council of Ministers to create a landfill, while one of the main conditions for the European loan is that the site should be solely for the wastewater treatment station. Hence, some fear the project may be suspended or canceled because of it.

Untreated Sewage

“Over the years billions of dollars have been pumped into the sewage and water treatment sector from north to south Lebanon, but none of the stations are working,” said Muhammad Ayoub, director of “NAHNOO” (We) Association, a non-governmental organization working towards an inclusive society based on good governance, public spaces and cultural heritage.

“From Ghadir and Bourj Hammoud to Tripoli, all of them are ineffective or nonfunctioning,” he said. “While these projects brought in huge funds, most stations were never completed or networks were not connected.”

According to the data obtained by NAHNOO, the total value of waste and sewage-related projects between 1992 and 2017 amounted to over $1.1 billion, while the Ministry of Energy spent a meager $60 million and the Beirut municipality another $50 million up to 2010.

“The state borrowed no less than $500 million to improve the sewage sector without any positive impact,” said Ayoub. “Most sewage today is still discharged without any treatment.”

Ayoub laid a big part of the responsibility for the failure of so many of such projects with CDR, which prepares the tenders and tender conditions and which, according to him, constitutes a major source of favoritism in the selection of contractors.

EU Investigation

“The EU blithely plows millions of dollars into environmental schemes without the slightest interest in how the money is spent – effectively encouraging big business and public officials to gorge themselves on the easy cash available,” British journalist Martin Jay wrote in May 2019 in a series of two damning articles investigating EU funded waste and environmental projects in Lebanon.

Jay among projects shed light on an EU-funded compost and recycling plant opened in Minyeh in the north of Lebanon, showing how the construction was “a blatant, crude sham,” orchestrated by a company whose only role was to produce “huge, bogus composting machines,” which were just empty drums solely built for the purpose of producing an allusion and pick up a half a million-dollar payout. The plant never produced a handful of compost.

Jay’s work shocked European MPs in Brussels and Strasbourg. Twenty of them, led by Portugal’s Ana Gomez and France’s Thierry Mariani, raised concerns about suspected corruption in EU-funded projects in Lebanon in November 2019.

“Besides the blatant misuse of European taxpayers’ money, this case requires an urgent and deep investigation by the EU, in particular the Anti-fraud Office (OLAF),” Gomez wrote in an open letter to OLAF. “Until those found responsible, both in the EU and in Lebanon, are brought to justice, EU funds for Lebanon are put under strict control.”

A group of independent European MPs is moreover plotting to recover more than $38 million thought lost in Lebanon over fake waste management schemes. They too wish to prosecute those responsible for the corruption.

Their concerns are based on multiple indications of corruption, yet most notably on a letter sent by Mohamed Nour Al-Ayoubi, an engineer and member of the Tripoli municipal council, to the European Parliament, in which he revealed suspicion of corruption in an EU-financed waste sorting project, which had not been properly implemented.

Launched in 2014, the 146.5 million euro project to clean and rehabilitate the Ghadir River seemed a great initiative. Yet seeing the endless delays, the CDR’s lack of pace, Lebanon’s political and financial crisis and, last but not least, a growing number of voices in the European Parliament calling for an end to corruption and accountability, the project may very well never see the day of light, and the people of al-Sellum may just have to learn to live with the rats, the stench and the garbage.

Read Also: