“There is a place for everyone,” said Nassim Ibrahim Levy, President of the Regional Council of Jewish Communities in Normandy in northern France. A statement that does not quite reflect the reality of Lebanon, the country Levy was forced to flee at the age of 21 – one year after the start of the Civil War in 1975, and a few years after his father got paralyzed.

“We suffered a lot and left everything behind,” Levy told Daraj. “I was still young when my father got paralyzed. He was cursed for being a Jew and hit on his back. It broke his spine.”

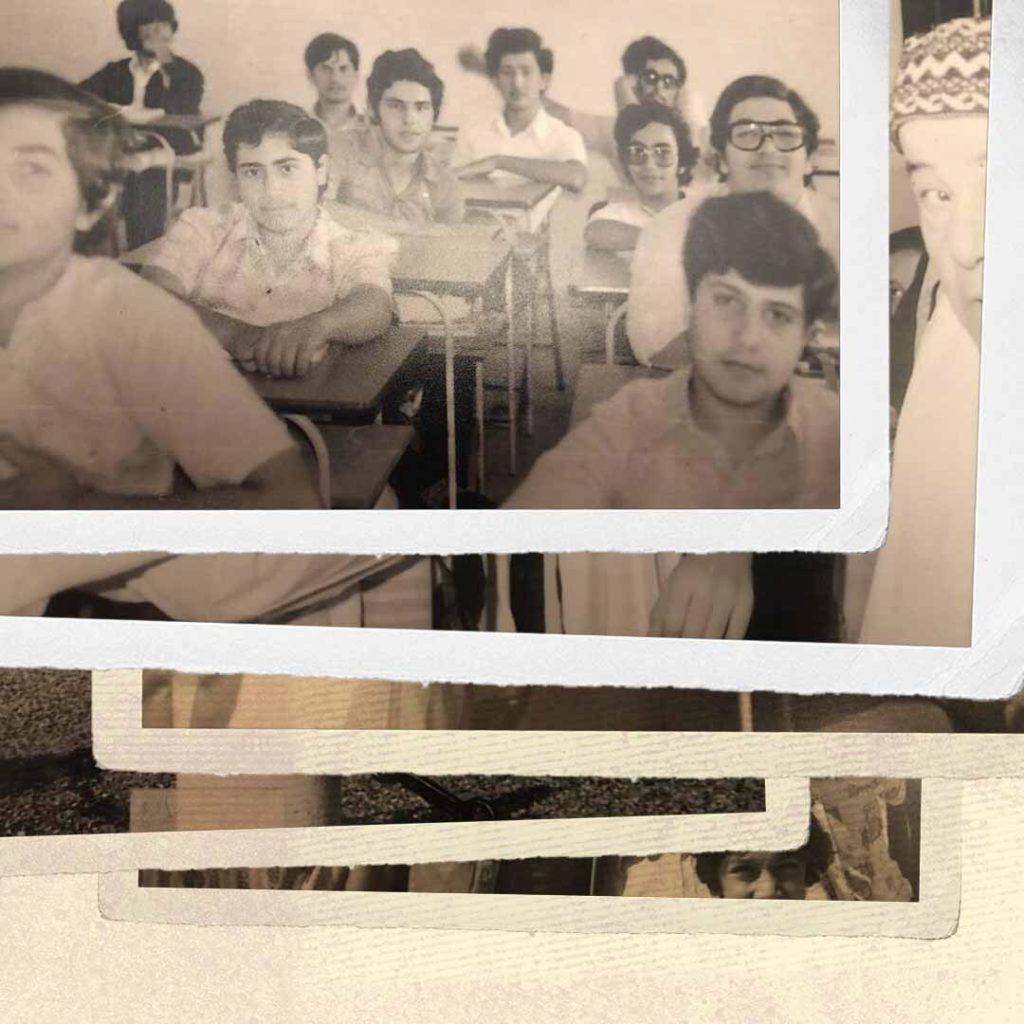

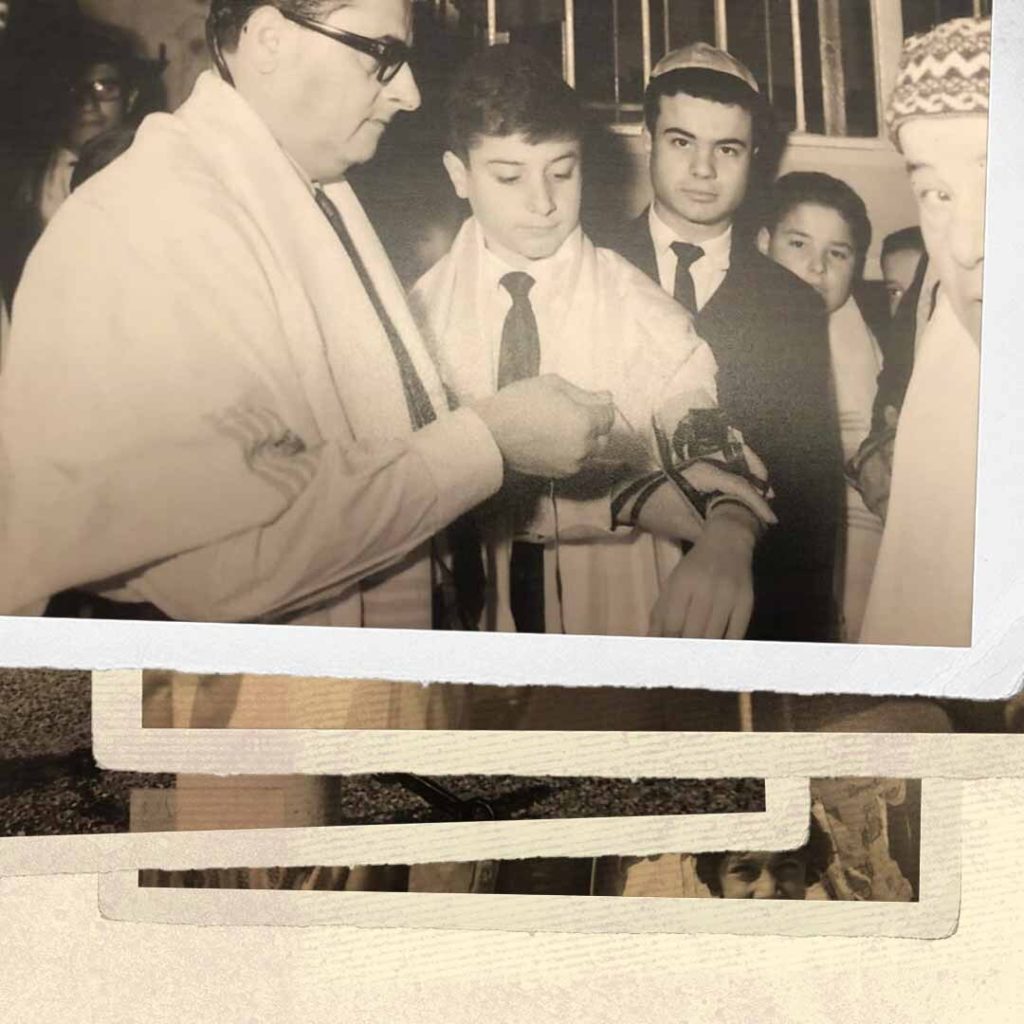

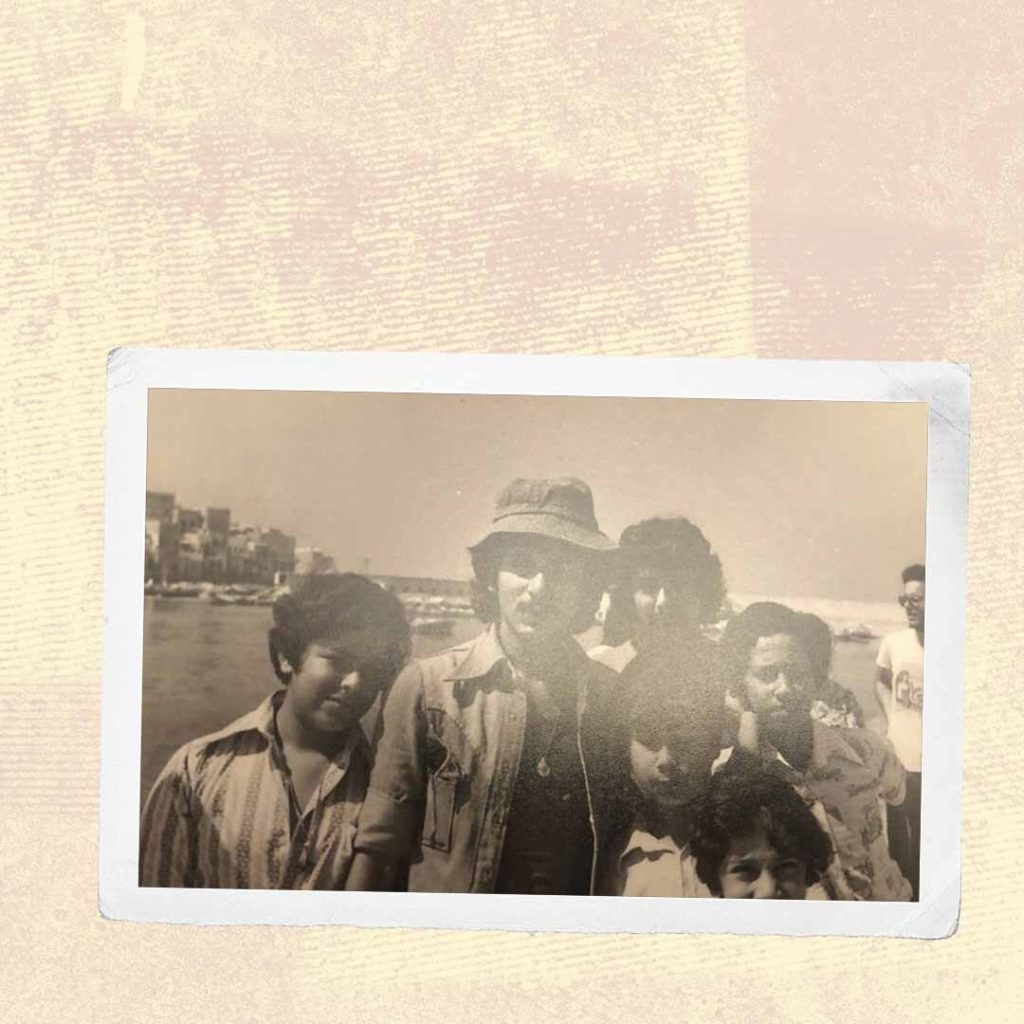

“My mother emptied large bags of rice to put our clothes in,” he continued. “We took our identification papers and emigrated. When we left our home in Saida, I only took pictures with me. We first went to Larnaca in Cyprus and from there moved to France. Our neighbors cried when we left. They loved us. But we were afraid.”

Levy, with his wife, three children and two grandchildren, still lives in France. He no longer uses his Lebanese passport, as he became a French citizen having married a French woman. Yet, he always kept his Arabic close at heart, and even taught his wife. “We used to listen a lot to Fairuz.”

“During the Civil War, Lebanon’s Jews were afraid, for we were considered Israelis, while we had nothing to do with Israel,” Levy explained. “Some people thought that ‘Israeli community’ meant ‘Israeli state.’ My grandfather had emigrated to Rio de Janeiro, where thousands of Lebanese Jews reside. But we did not have enough money to catch up with them.”

Levi still remembers the names of his neighbors’ in Saida. When he remembers his mother, he becomes a bit emotional. “Her name was Maryam,” he said. “They used to call her Saint Mary. She owned a small shop on Riad el Solh Street in Saida. Unfortunately, her work was affected by the war and she was no longer able to enroll us in the French school where we studied. We were not against anyone, but some people became against us.”

“After they took some French hostages, they also took hostages from the Jewish community in Lebanon,” said the head of the Jewish parish in Normandy, who preferred not to accuse one specific party.

We initially addressed Levy in Arabic, but he seemed at first not at ease, so we changed to French. Yet, after he became comfortable with us and the conversation, he himself started narrating events in Arabic, and expressed his happiness for being able to speak in his mother tongue. While Levy serves as head of the Jewish communities in Normandy, his heart is still with Lebanon.

“We grieve for what is happening there and we pray that the country may live in peace,” he said. “I no longer have family in Lebanon, but I still have my old friends who belong to different sects. When my daughter got married in France, they all came.”

Embassy

Although he still cares for Lebanon, he is clearly not thinking of returning. “In the current situation? Of course not. Today, a visit to Lebanon would be madness.” he said. But he dreams to one day be able to make an official visit when the country is in better conditions.

On November 1, Lebanon’s ambassador to France, Rami Adwan, hosted a gathering of dozens of French Jews of Lebanese descent. He asked them for support and even encouraged them to return home. Four generations of Lebanese Jews who left the country in separate waves over the past century attended the event at the embassy in Paris. According to Levy, the initiative was “exceptional.”

“I appreciated a lot when the ambassador said that the Lebanese state should have protected the Jews,” he said. “What he said is true for every citizen, not just the Jews.”

Levy hoped Adwan would one day become Lebanese president. However, he wondered why the event was partly linked to the upcoming parliamentary elections, in which he and other Lebanese Jews abroad are allowed to vote. “What can fifty people do?” he asked.

Historian

Also present at the Lebanese embassy event was Lebanese historian Nagi Gerji Zeidan, who published the book Juifs du Liban (Jews of Lebanon). As publishing the book in Lebanon faced difficulties, it was issued in France.

According to Zeidan, it is not easy to work on the issue of Jews in Lebanon. Suspicions quickly arise due to the (unjust) link between Judaism and Zionism. When working on his book, Zeidan was summoned for interrogation by the military to clarify his research. Zeidan described the meeting at the Lebanese embassy as “wonderful.” The ambassador had paid attention to every detail and even provided “kosher” food, which is the food allowed to be eaten under Jewish law. He for example provided bread with specific specifications, so that it did not contain milk and butter at the same time. The food was blessed by France’s chief rabbi Haim Corzia.

Zeidan has been studying Lebanon’s Jews for some 27 years. He does not agree with the estimate that there are still some 200 Jews living in Lebanon for he cannot acknowledge what has not been properly documented.

“They live in fear and have changed their names,” he said, adding that the head of the Jewish sect in Lebanon, Isaac Arazi, is not Lebanese. According to him, the number of Jews residing in Lebanon today is only 27 people. “But they hide their religious identity.” For the historian, the embassy meeting was a dream come true, as it brought together some 53 Jews of Lebanese descent, among whom some “of Lebanon’s once wealthiest Jews, such as the Cohens, Levi’s and Hallaqs, who used to own banks in Beirut.”

Among those who attended was Andre Hallaq, son of Elie Hallaq, the Jewish doctor who was kidnapped and murdered in 1985. According to Zeidan, Elie Hallaq refused to leave for Israel, holding on to his Lebanese nationality, until he got killed.

Bodies

Regarding the possibility that ambassador Adwan’s initiative could constitute a return for Lebanese Jews to their homeland, Zeidan asserted: “They will not return.”

There is an issue that arguably weighs heavier than the current financial crisis. Nine Jews were kidnapped and murdered during the Civil War in 1985. And the location of their remains is still unknown.

“At least they want the bodies,” said Zeidan avoiding to name the faction that stands accused of this crime. But according to him a settlement could be reached to find and bury the remains without addressing responsibility.

“This also happened in the case of French researcher Michel Seurat, who was assassinated in Lebanon in 1985,” he said. “The location of his body was revealed in 2005 in a settlement with Hezbollah, without anyone taking responsibility for the crime.”

Problems

Zeidan revealed a quest to one day gather all Lebanese Jews of the world and he sent a message to Lebanese President Michel Aoun, telling him about the discrimination Lebanese Jews suffer abroad.

“When trying to renew their Lebanese passports, Lebanese Jews suffer a lot, as they are asked to go to the Ministry of Defense for an investigation to see if they visited Israel before they can renew their passport,” he said. “This did not even happen to Antoine Lahad, who was an Israeli agent. He could obtain a passport directly from the Lebanese embassy without going to Lebanon.”

He also pointed at the trouble for Jews obtaining other papers, such as birth certificates. They ask their representative in Lebanon, lawyer Bassem el-Hout, to secure such things.

Lebanon’s Jews once owned a lot of property in Wadi Abu Jamil in Beirut, which was known as the Jewish Valley. Yet, Solidere “robbed” many of these properties, according to Zeidan. It even tried to “rob” the Magen Abraham Synagogue, but the US embassy prevented it. Today, the synagogue has been fully restored.

Spies

While some historians claim that Jewish emigration from Lebanon began after the 1967 war, due to an increase in hostilities, Zeidan distinguished between Syrian Jews, who came to Lebanon, and Lebanese Jews. According to him, the migration of Lebanese Jews began way before 1967, as a result of intermarriage between Lebanese and Palestinian Jews. In those days, Jews could move freely between Beirut and Haifa and naturally did so due to their family relations. He claimed the Israeli army in the 1980s tried to persuade Lebanon’s Jews to go to Israel, but they refused.

“The Lebanese Jew is not an agent of Israel,” asserted Zeidan. “His main concern was to earn money. He had no political interests.” Zeidan even has documents that prove that two Lebanese Jews between 1948 and 1990 worked as spies for the Lebanese state to monitor Zionist activities in Wadi Abu Jamil. “One of them was kidnapped and killed by Hezbollah,” he said.

Secret Visits

Over the years, only a few Lebanese Jews have visited their homeland in secret. They all go to Wadi Abu Jamil. As for the number of Lebanese Jews that has been included on the electoral lists and therefore have the right to vote, they amount to some 4300. However, according to Zeidan, the figure is not accurate, as it includes many people who died, yet whose deaths were never recorded.

History has been cruel to everyone in Lebanon, yet the suffering of the Jews had an extra dimension, as they were one of the small minorities that could not protect itself. The tragedy was only increased by unjustly linking them to racist Israel, holding them responsible for that state’s actions.

Despite such suffering, Levy expressed his wish for the peace and wellbeing for Lebanon. “That day will be the most beautiful, and I hope we will all be alive to live the moment.”

Read Also: