“I have three daughters: Sometimes, we have to buy sanitary pads on credit. The owner of the shop is patient with us.”

Zahra, a Jordanian woman in her forties, has seven daughters and seven sons, the last of whom was born about a year and a half ago. The large family can barely make a living, as the head of the family is a daily labourer who works at the local market.

“They all get their periods on the same day, on the twenty-seventh of every month,” Zahra jokingly says. She stated that each one may need one or two packs, which means that she needs around six Jordanian Dinars ($8.5) to buy them per month.

Previously, Zahra would get free sanitary pads from a center near her home in Sweileh, north of the capital Amman. She described the quality of the feminine pads as “poor, and they fall apart.” Sometimes, she would receive ten dinars as financial support to attend educational sessions, which she then spends on pads. Now, however, she buys baby pads by the kilo and adapts them as sanitary pads for her daughters.

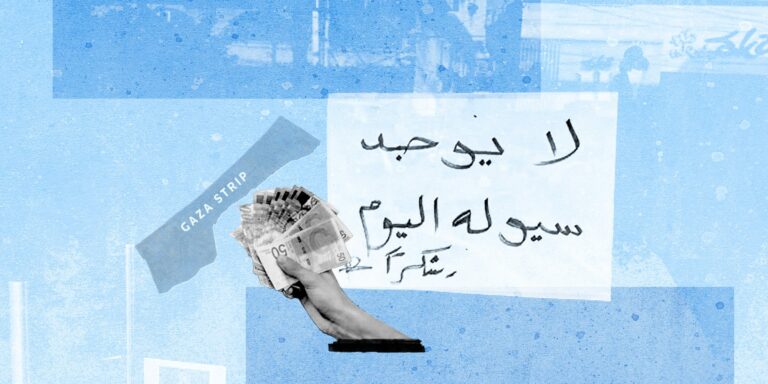

Sisters Salma and Suad stay at home for days sometimes if they cannot buy sanitary pads. One of them explains, “We try to buy the pads on credit. I swear to God, the shop owner refused to sell them to us lately because we owe him a lot of money.” Due to this, they wait for a male family member to buy the pads for them. Until then, the sisters resort to using substitutes like tissue paper or pieces of cloth.

Sanitary pads may seem inexpensive, but they become a burden for families that can barely make ends meet, especially in a country where the poverty rate has reached 15.7 percent, according to the latest census conducted in 2018. Three years ago, the World Bank highlighted that the national poverty rate in Jordan may rise by about eleven percentage points to reach 27 percent.

There isn’t a standard price for feminine hygiene pads in the market; we found pads that cost sixty-five piasters ($1), and some that exceed six dinars ($8.40). Evidently, imposing a sales tax on a basic commodity that is so important for female health would raise its price and sometimes even double it, making it unaffordable for many.

Women resort to inexpensive alternatives

Zahra is not the only one who resorts to alternatives, as several women are turning to less expensive options. Aminah says, “I would feel embarrassed in front of my mother as my sister and I had to bring strips of cloth, cut them up, and wear them, and we would change them the next day. Then, we would sneak up to the roof to wash and dry them.” This process would be repeated several times until the rags dry up, so they could reuse them.

Aminah remembers the stinky odor, the chronic infections, and the itching resulting from wearing the same pad for a whole day. Her suffering stopped after she gave birth and started breastfeeding.

Today, Zahra works as a maid in a school in the south of Jordan. She says that the same scenario is repeated among students: “The bathroom is filled with strips of cloth; they do not know about sanitary pads.”

Feminist researcher Reem Khashman points out that the use of rags is the least harmful alternative, but it is a burden in areas that suffer from water shortages or in places where it is difficult to access toilets safely. Through her field visits and meetings, Khashman found out that some women use toxic and harmful alternatives, such as newspapers.

She also explained that the inability of families to provide sanitary pads for their daughters push them to wrong practices, such as using one pad over two days.

“Usually, a woman needs two packs to last her a cycle,” says Khashman

According to Khashman, a point of discrepancy arises in households: She notes that the head of a family prefers to buy chicken, for example, over buying pads for three or four girls in the family, which would eventually cost him ten dinars a month ($14). This makes the girl unable to use pads at all, so she stays in her room throughout her menstrual cycle.

“[Sanitary pads] are expensive: We think of them as cheap because we are able to buy them since we have an economic safety net. In underprivileged areas, in pockets of poverty and refugee camps, this network does not exist; food security does not even exist.”

Khashman stresses that a discussion about menstrual products should not be limited to feminine pads but must extend to many other products and services. The issue of the high cost of sanitary pads and access to them are two of many other issues that affect women’s health, and they all fall under the category of what is known as “period poverty.”

Menstruation is not an option

According to Taqatoaat and the United Nations Population Fund, period poverty is a new term: It refers to the lack of access, or inability to access, health products related to and appropriate for the menstrual period; and other similar health services; and to water facilities related to personal hygiene, health education and waste management methods.

Feminist activist and Executive Director of Taqatoaat, Banan Abu Zeineiddine, points out that the root of the problem is that feminine pads are not viewed as a basic commodity.

She explains that sanitary pads are considered commercial and luxury goods, and the proof to that is the high taxes imposed on them. They are not available everywhere and are not categorized as a health care requirement. The fact that they are not available for free in health centres and girls’ schools confirms that it is not considered an essential commodity.

According to UNICEF, a woman spends about seven years of her life menstruating. A quick calculation shows that a woman may spend up to 3,000 Jordanian Dinars ($4300),throughout her life on sanitary pads, assuming she may use three to five pads per day. It is worthy to note that the length of the menstrual period, and the blood flow, is different from one woman to another.

The percentage of women whose ages range between 15 and 54 is about 56.1 percent of the total number of women in Jordan.

Abu Zeineddine links women’s health to their stereotypical or social role: They are not viewed as citizens entitled to health care. Single girls feel excluded because they are afraid to go to maternity and child care centers to avoid the social stigma, because of their young age and the fact that they are not married. Abu Zeineddine stresses that women menstruate for most of their lives, especially if we take into account that menstruation may begin as early as seven and eight years of age due to climate change.

Sanitary pads are a luxury

In an obtained list from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry on what is considered as an “essential commodity,” we counted fifteen products considered as essential. These include wheat, barely, bran, buckwheat, sugar, milk, and chicken among others.

Wael Klob, the director of Market Supplies Monitoring at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, says that the criterion for selecting basic commodities is based on what is believed to be essential for citizens. The Minister also has the right to request the Council of Ministers to add any other products to the list of basic commodities.

Klob explains that the state monitors the prices of basic commodities and their strategic stockpile directly, and it makes sure that quantities of these supplies can cover at least three months for commodities such as rice, sugar, and one year for wheat and barley at all times.

Economic expert Ra’ed Al-Tal defines basic commodities as what citizens purchase every day. There are several criteria for determining what form a basic commodity, the most important of which is the level of need for the product and its consumption and health benefit to the citizen.

Governments around the world are trying to exempt these goods from taxes and to make them accessible to people at affordable prices.

“Blood in Prison” Menstruation is a Humiliation Tool for Female Prisoners in Egypt

Taxing blood

Our enquiry with the Jordanian Ministry of Commerce and Industry revealed that listing women’s pads within “towels, sanitary products, liners, diapers, and pads for children” comply with its global classification. A general sales tax of 16 percent and a customs fee of 15 percent are imposed on feminine hygiene pads. This tax could only be amended through a decision by the Council of Ministers.

Dr. Ibrahim Al Hunaiti, a tax consultant, explains that the rule is that all goods are subjected to a 16 percent tax, while the rest are exceptions. Al Hunaiti says that the sales tax and other indirect taxations are unfair because this is passed onto the final consumer. He adds that this is imposed on all classes of society and does not account for the (weak) purchasing power of some. He points out that Jordan’s revenue depends on the sales tax imposed on goods to a large extent.

The sales tax schedules show that there are some goods which are exempted from sales taxes, and others with reduced taxes.

Al Hunaiti adds that imposing sales tax on goods will naturally raise the final price of the product and may even double it sometimes. This is in addition to customs fees, which may reach 15 percent on some goods, raising their cost further. In this way, the consumer may pay one dinar for a commodity whose original value is half a dinar.

The longer the transport chain gets from the source to the merchants and finally to the consumer, the higher the price becomes.

Al Hunaiti previously worked in the tax department and confirms that the decision to exempt a commodity from taxes or change the value of the tax is in the hands of the Council of Ministers, and comes about as a result of pressure from civil society organizations or the Council of Ministers. Al-Hunaiti explains that it is possible to change the tax on one item only, even within a family of commodities that fall under the same category, without the need to change the classification of all the other goods.

Unsanitary pads

A research paper published by Taqatoaat recommends that feminine hygiene pads be classified as a sanitary product, and that they fall under the jurisdiction of the Jordan Food and Drug Administration, because commodities that are classified as medicine are subject to a reduced tax rate of 4 percent, with some exceptions. In many countries like the United States, feminine hygiene pads are considered a sanitary product; the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a medical device/product as “a device intended for diagnosing disease or other conditions, or in the treatment, mitigation, or prevention of disease.”

We contacted the Jordan Food and Drug Administration to find out why sanitary pads are excluded from their list. Their response was that feminine hygiene pads are not medical supplies and are not used for medical purposes; therefore, this definition does not apply to them. Accordingly, any approvals regarding their import and examination would not fall under the authority of the institution.

On the other hand, condoms are analysed for compliance and registered at the Jordan Food and Drug Administration through the Directorate of Medical Supplies. These cannot be allowed into the market before making sure that they conform to international standards and pass a laboratory examination. This also applies to bandages and cotton used in many medical areas.

Additionally, it is difficult to know what goes into the manufacturing of feminine hygiene pads; none of the types of pads available on the market list their composition. We contacted a factory for making sanitary pads and were told that they use fibrous materials made of polyethylene. The absorbent layer consists of porous materials made of wood and polyester fibres. This aligns with the description published online for another type of sanitary pads.

Ahmad Younis,a specialist in women’s health, and dermatology, states that polyethylene is a very common type of plastic which is used in manufacturing sanitary pads and is safe for human use. Younis adds that there is evidence indicating that some harm may result from plastic materials, but more studies and scientific research in this field are needed, as he called for more “oversight.”

Doctor Lamis Laqi, a general practitioner at the King Hussein Foundation in the Deir Alla region, sees many wrong practices by patients during their menstrual cycle, including not changing their pads at a suitable pace. The area where the pad is placed is damp, dark, and high in temperature which makes for a suitable setting for the growth of fungi and bacteria. The longer these pads are used, the higher the moisture in the area. This causes opportunistic infections to develop, which may lead to infertility in the future.

If the infections are not treated, they can reach the pelvis and affect pregnancy or lead to premature births, problems, and infections with the foetus, as well as blood poisoning in foetuses after pregnancy.

Missing data and timid claims

Calls for the exemption of women’s sanitary towels from sales and commodities taxes are on the rise, and some are calling for the inclusion of feminine hygiene pads as a basic or sanitary requirement. Scotland was the first country to make menstrual products available for free. In the United States, feminine pads are classified as sanitary products and are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration affiliated to the US Department of Health. In India, a 12 percent sales tax used to be imposed on female pads, but these products were exempted from taxes starting in 2018. In Sudan, sanitary pads are now provided as part of health insurance packages whereby women only pay half the cost. Meanwhile, such measures are absent in Jordan.

Reem Khashman, a feminist researcher and activist, believes that there should be studies that measure the extent of the problem and figures that reflect the reality of the current situation regarding period poverty. She is demanding that sanitary pads be included in the list of medical supplies. As such, the state would become responsible for dispensing them in its health centres. Manufacturers would also produce them at a cheaper price, and they would be provided free of charge, similar to services related to reproductive health.

Khashman’s demands are not limited to recommendations, as she is involved in some recent initiatives on the matter. Two months ago, she called on women across the country to put sanitary pads in charity parcels. “There is a shortage in women’s pads: Why don’t charity parcels contain these pads? Basic commodities are not limited to lentils, rice and vegetables,” she said.

According to Khashman, the lack of access to these goods hinders girls from accessing work and education. “We should not wait for a catastrophe, an earthquake, or refugee influx to determine how necessary these products are,” she says.

The study conducted by Taqatoaat offers several recommendations. First and foremost, they recommend that women’s pads be included under the authority of the Food and Drug Administration; distributed free of charge in health centres and schools; and given to women in the puerperal or postpartum period. This is in addition to reducing sales taxes on them, exempting them and the product components from taxes, and allocating funds as part of the national aid to buy menstrual products.

After Aminah gave birth to her first son, she found a way out of menstruation and its necessities through breastfeeding. She will not need to buy feminine pads until further notice. The other women we met, however, will continue worry about buying pads, replacing them, and finding cheap alternatives for years or even decades to come until they can obtain them for free, or at least until the state stops taxing a commodity that is anything but a luxury.