Contributor to the Reporting: Ibrahim El Gharib

This investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

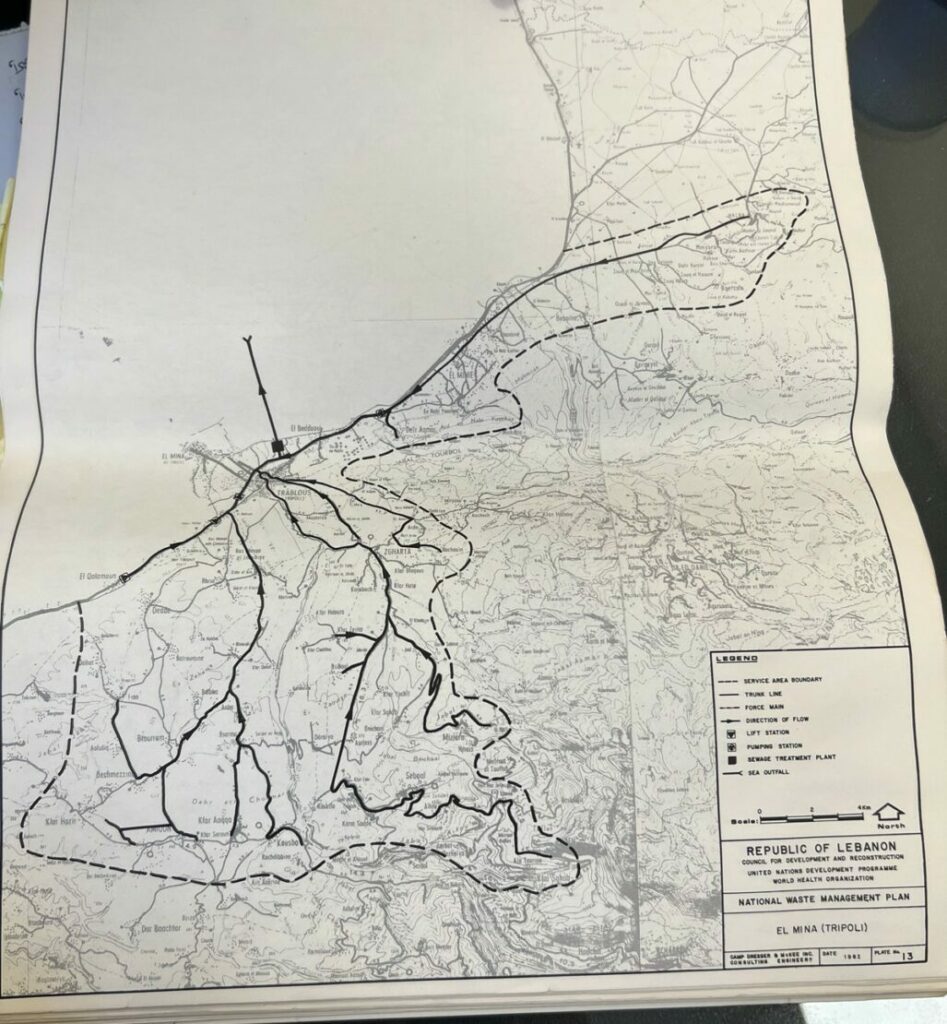

Just a few meters away from the bustling vegetable market in Tripoli, lies the sprawling Northern Lebanon wastewater treatment facility – the largest in Lebanon and one of the biggest on the Mediterranean coast. Anyone passing by, observing its size and advanced technologies, would anticipate an ideal scenario with no water pollution in northern Lebanon. Fourteen years after its completion, this facility continues to operate at a minimum level, only performing the preliminary treatment, which involves removing solid objects and large debris from the wastewater. Why is this the case, despite the facility costing over 100 million euros?

“Why do we have these significant investments, whether they be acquired through aid, loans, or treasury financing from the government, that remain unused and only generate problems? Our station cost nearly 100 million euros, if not more, to build, and we haven’t even established a good network. This indicates poor planning and a lack of coordination between building networks and station construction. Consequently, most of our rivers and beaches remain polluted or are being given lower priority for treatment,” says Dr. Nasser Yassin, Minister of Environment, in an interview with Daraj.

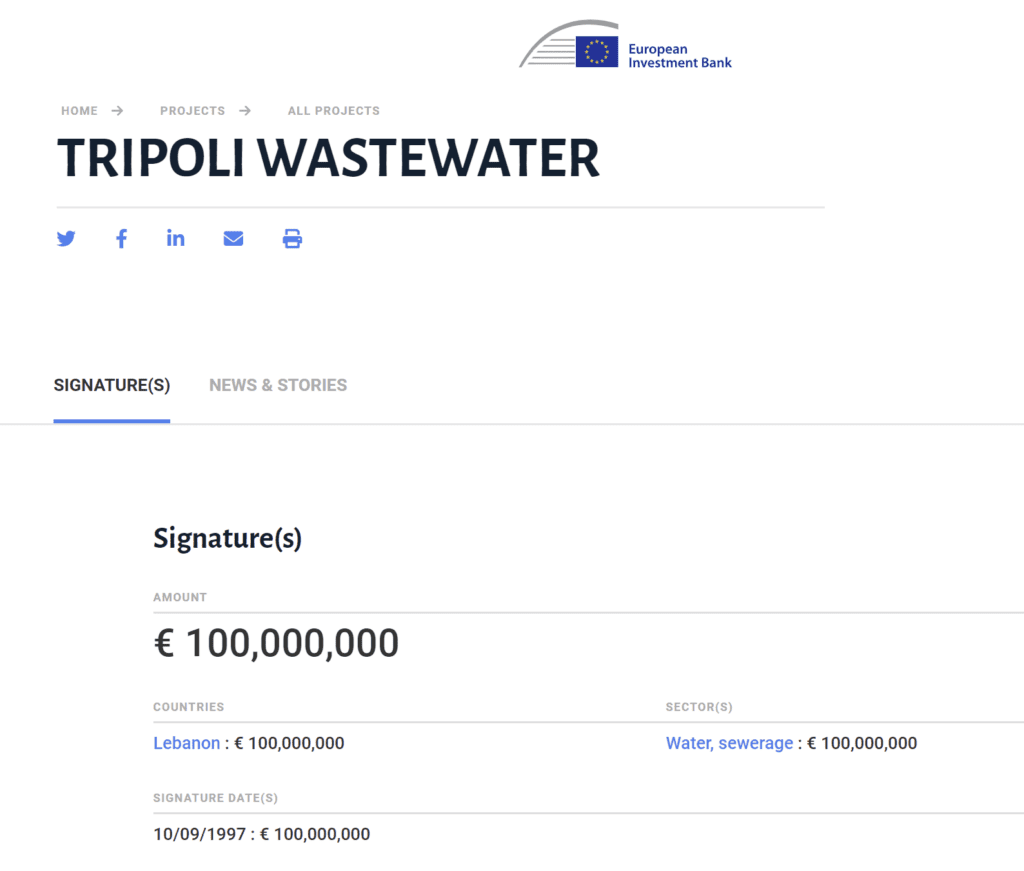

In the second half of 2019, the Lebanese government and the European Investment Bank (EIB) signed a financing contract to support the establishment of a sewage network in the city of Tripoli and its surroundings under the name: “Greater Tripoli Basin WasteWater Networks.”

Due to the outbreak of the financial and political crisis in October 2019, the EIB halted its projects in the country and hence, the “Greater Tripoli Basin Wastewater Networks” loan, signed in 2019, has not been disbursed. However, the agreement with the EIB included an 18 million EUR grant, which is still available for use, as per EIB’s email to Daraj.

According to the Council for Development and Reconstruction, Tripoli’s facility “protects the shore, but it doesn’t protect the sea.”

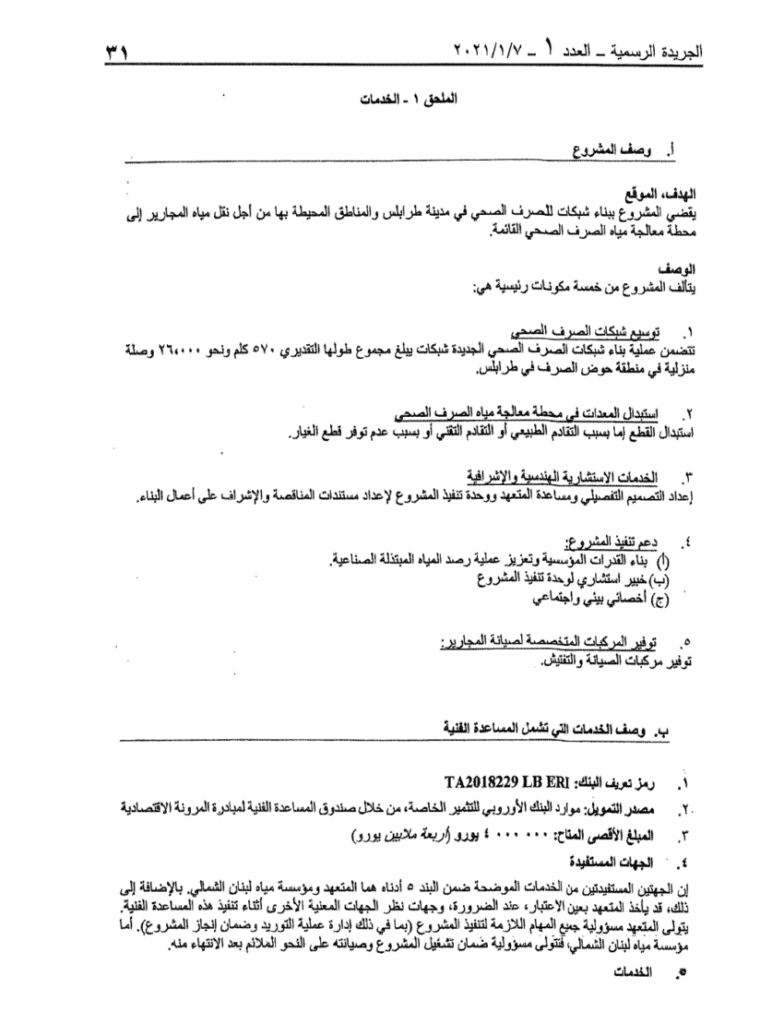

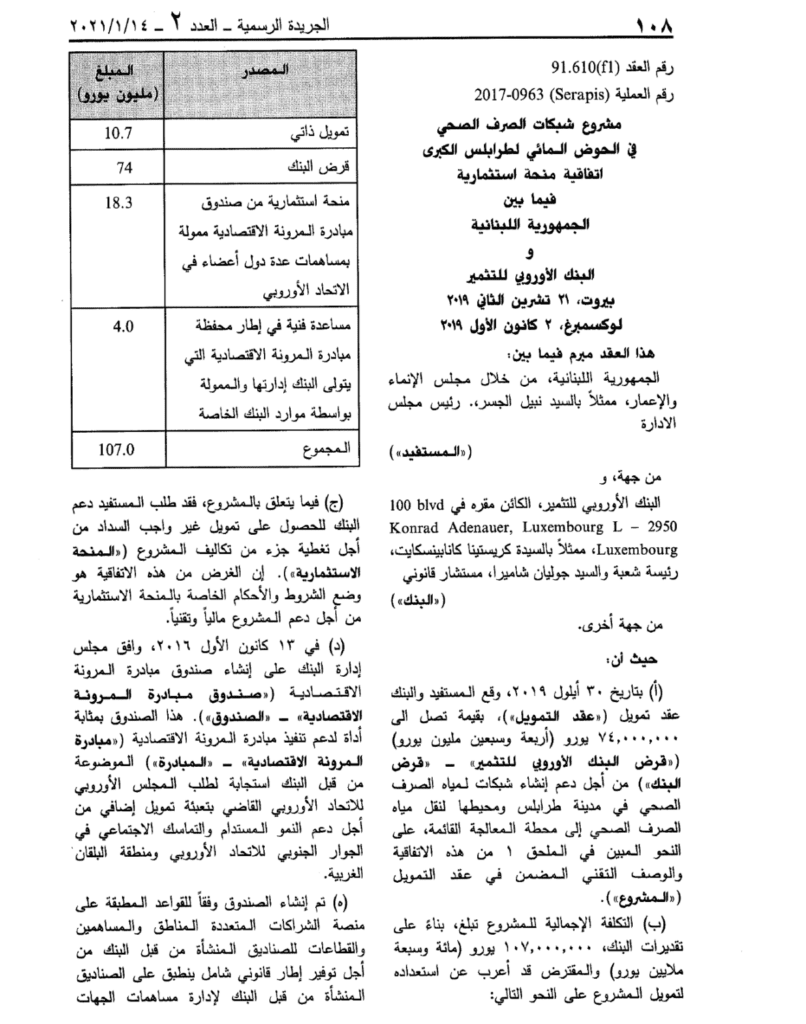

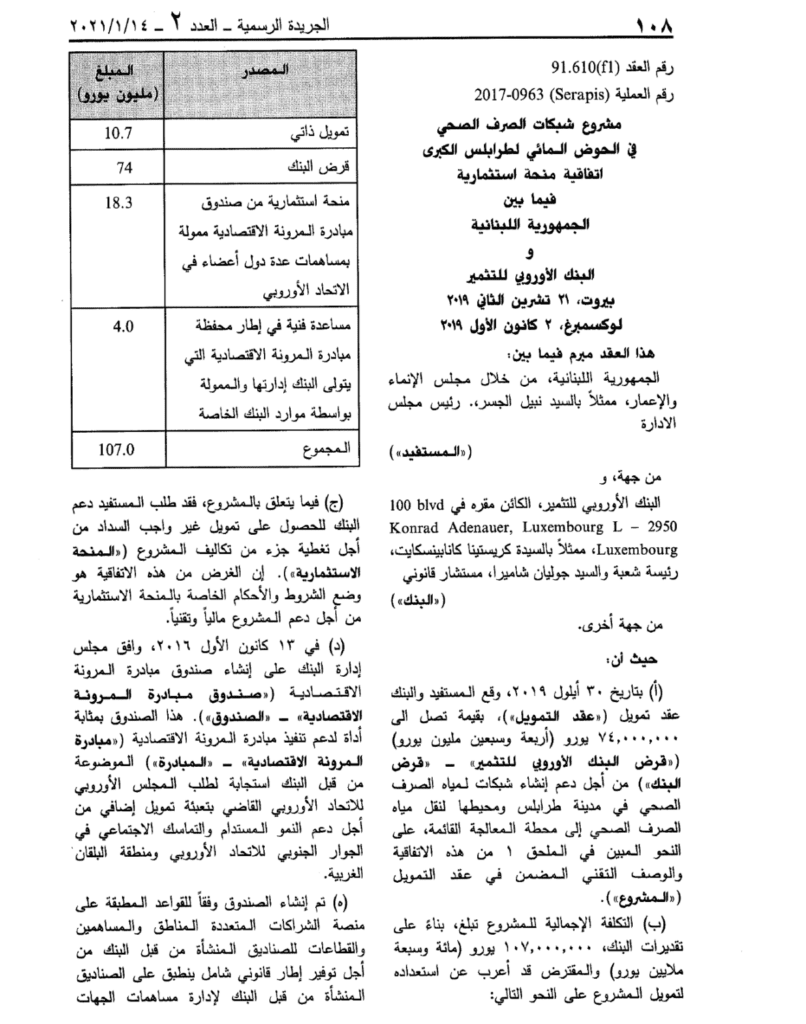

Project Funding:

The project cost a total of 107 million EUR, encompassing a 74 million euro loan, an 18.3 million euro investment grant from the Economic Resilience Initiative Fund –funded by contributions from several EU member states, and a second grant of 4 million euros as technical assistance. Thus the EIB’s contribution amounts to 92 million euros while the Lebanese government covers 10.7 million euros.

Following the outbreak of the Lebanese crisis, the EIB put the project and specifically the loan on hold, while also confirming that the grant from this project is still available.

| Source | Amount |

| Self-financing | 10.7 million euros |

| Loan | 74 million euros |

| Investment grant from the Economic Resilience Initiative Fund, funded by contributions from several EU member states | 18.3 million euros |

| Technical assistance within the framework of the Economic Resilience Initiative portfolio managed by the bank and funded by the bank’s own resources | 4 million euros |

| Total | 107 million euros |

According to Yassin, the real issue lies in the absence of proper management of the sewage sector. “We’re not talking about ordinary matters here; we’re talking about a sector that directly affects people’s health and lives, especially with the Cholera outbreak last summer,” he says. The CDR remarks that if the Tripoli facility didn’t exist during the Cholera outbreak, “God only knows what would have happened.”

“What are we waiting for?” asked environmental expert and researcher Dr. Yasmin Jabli. Within one year, we had Hepatitis A and Cholera, waterborne diseases, spread in our area. What else are we waiting for? 99% of our water is contaminated. It’s a shame, with all the money we’ve received, we can create better treatment plants and implement waste management strategies.”

Project Background:

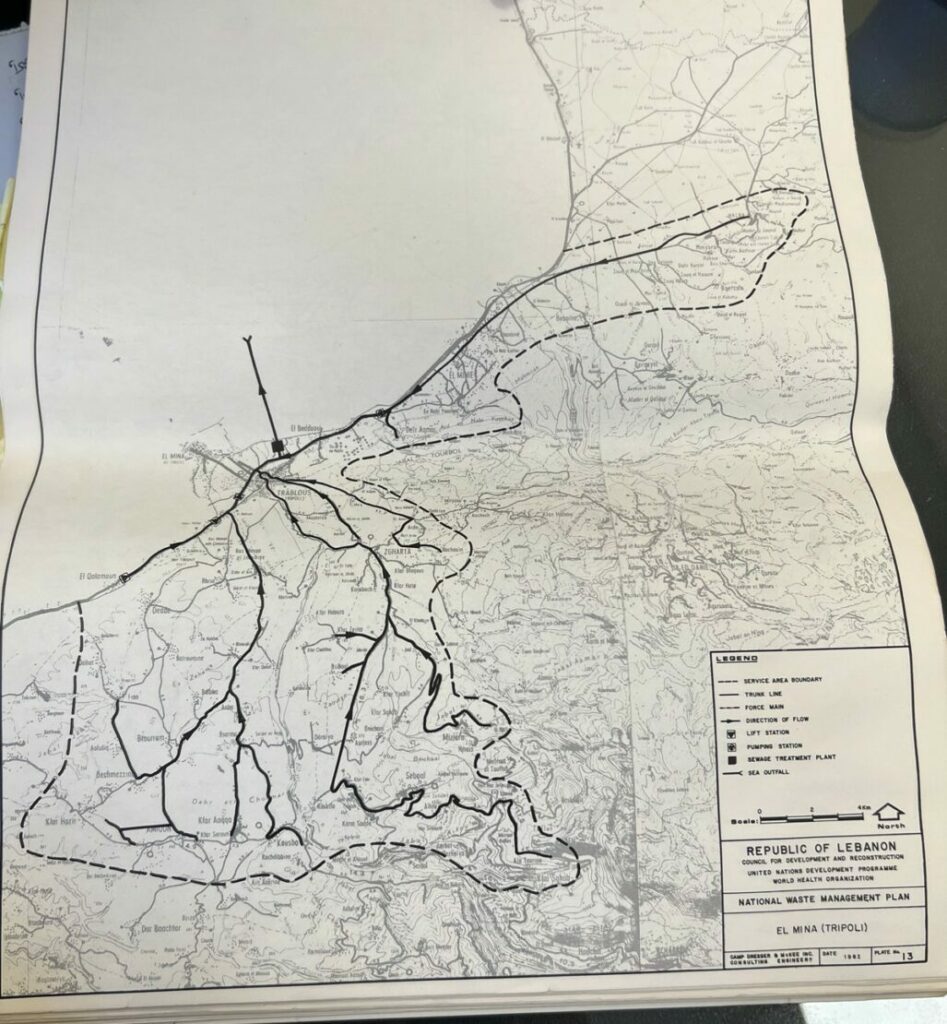

As part of the European Investment Bank’s cooperation with the Lebanese state since 1978, which includes investments totaling 2.7 billion euros in the country, a loan of 100 million euros was approved to build a wastewater treatment plant in 1997; a sea outfall extending 1.6 km into the Mediterranean Sea was also constructed. The project began in 2003 and was completed in 2009.

In 2019, the bank approved a second loan for the purpose of completing the networks. According to the European Investment Bank’s website, this project will improve sanitation services for approximately 900,000 residents of Tripoli. It began over twenty years ago as a priority within the government’s Coastal Pollution Control Programme, aiming to achieve compliance with the Barcelona Convention and the Genoa Declaration on the Second Contract for the Mediterranean in 1985.

According to the bank, this sewage project is a priority within the European Union’s “Horizon 2020” initiative, which aims to clean up the Mediterranean Sea. It is also aligned with the objectives of the maritime component of the European Union Water Initiative, which promotes better water resource management and coordination among stakeholders.

While the project intended to cover the most advanced water treatment methods, the plant only performs minimal treatment. Why is that the case? For today, 20 years since the beginning of the project in 2003, the plant still has not received the minimum capacity of wastewater (60 m3) to operate on advanced levels.

To this day, the station does not receive more than 45 m3 of wastewater. Yet, after establishing the needed networks in both the Koura and Qalamoun areas, the water volume is expected to reach the threshold allowing the station to operate normally, according to EIB.

Electricity Shortages:

The EIB explains that the situation is increasingly complicated due to the electricity shortages and the prohibitive cost of private generators. On a similar note, Jabli questions the decision to establish a facility of this size and technology, given the electricity and funding problems.

Yet, to face this, the European Union “has teamed up with UNICEF to finance operation and maintenance in the wastewater sector in the next 2 years with an envelope of nearly 30 million euros… For instance, this model has been successfully tested at the wastewater treatment plant in Zahlé, where another donor is working with a UN agency to keep the plant in operation,” as per the EIB.

“Missing Management”:

Dr. Nasser Yassin, the Minister of Environment, describes the situation of Tripoli’s wastewater treatment plant, on his social media accounts as: “The Missing Management,” questioning why the largest wastewater treatment facility in Lebanon has been only operating at a limited level of its capacity, with most of its equipment still new. Yassin attributes this to: “the absence of proper planning, effective management, and serious oversight for decades, resulting in failures in many sectors as well as the return of cholera. Numerous environmental facilities have become neglected, inactive, or susceptible to vandalism and theft.”

In a similar context, environmental expert and researcher Dr. Yasmin Jabli, also questions the management and planning approach in her interview with Daraj. “In Lebanon, we are doing things backwards. Instead of starting with the infrastructure and working in parallel on building the station and making connections, we built the station first and then looked at the connections.” She describes the station today as a “bird sanctuary,” due to its lack of functioning and harboring of some wildlife. Environmental expert Dr. Monzer Hamze shares the same concern: “Is it reasonable for the station to exist, costing a significant amount for maintenance every year, while the shore and Abu Ali River continue to be polluted? It’s not acceptable to wait for years for networking processes.”

This view is a;sp shared by one of Tripoli’s two heads of municipalities, Dr. Riad Yamaq, who speaks of the municipality members’ rejection of the project’s scale in the past, especially given the lack of trust in the results of these developmental projects and concerns about large quantities of untreated wastewater entering the city. The lack of trust also stems from the ineffective monitoring in previous projects, especially with contractors who prioritized their personal interests over Tripoli’s welfare.

It is worth noting that the CDR is the governmental body responsible for implementing such projects. The CDR mentions that given the country’s circumstances, building this plant was necessary. The cost of the plant today, excluding networks, would not be less than 170 million euros, while it was built along with the sea outfall for 100 million euros (excluding connections).

In this regard, Yassin, Jabli, and Hamze emphasize the importance of the plant and the technologies used, if invested correctly. This sentiment was also reiterated by Tripoli’s mayor, Ahmed Qamareddine, who called for securing the necessary funding to complete the connections. Thus, untreated wastewater continues to be discharged into the Abu Ali River, according to Yassin and Qamareddine. Yassin believes that “Lebanon lacks management, especially in sewage management, not knowledge or technology.” Both Yassin and the CDR affirm that the European Union is aware of the current situation and what the station lacks.

Pollution of the Abu Ali River

The problem in Tripoli is complex, as it is not limited to sewage water alone, but also includes pollution of the Abu Ali River, soil contamination in areas adjacent to the waste dumps, poverty, and the absence of the state.

The Abu Ali River holds a significant place in the memories of the older generation in Tripoli. Before it flooded in the 1950s, it was a place for swimming, drinking clean water, and utilizing its resources. However, after the flood, the city’s landscape changed as the river became surrounded by cement, “causing the current generations to distance themselves from it and treat it as a channel for waste and sewage,” says Baker Saddiq, the president of the Archaeological Club of Tripoli, in an interview with Daraj.

Similarly, the environmental expert Dr. Monzer Hamze, criticizes the previous decisions concerning the Abu Ali River, such as demolishing the historical buildings that surrounded it and replacing them with concrete walls. In an interview with Daraj, he criticizes the current state of the river, which instead of being an attractive area for investment, has become surrounded by poverty belts and waste dumps.

In this context, Nasser Yassin believes that the river should be viewed comprehensively, not just as a geographical area, but as an integral part of the city’s history, present, future, residents, and civilization.

Studies conducted by Dr. Yasmin Jabli indicate that the Abu Ali River contains high levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which result from fuel and scattered combustion. The studies revealed significant pollution in the river, including various pesticides, some of which are banned in Lebanon. The percentage of pesticides exceeded the limits set by the European Union in most of the analyzed wells.

However, once the connections are completed, the treatment facility is expected to improve the current situation and reduce water pollution both in the sea and in Abu Ali’s River.

Despite its impressive scale and advanced technologies, Tripoli’s wastewater treatment facility, the largest in the country and one of the Mediterranean’s largest, remains underutilized. With over 100 million euros invested, and two decades since the beginning of the project, the facility is not yet living up to its intended purpose, still working at a minimal capacity due to a shortage of wastewater inflow, incomplete connections, and ineffective long-term planning.

The Tripoli facility safeguards the shoreline but fails to safeguard the sea, which does not fulfill either the EU’s or the Lebanese aspirations.