This investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Nearly one million Tripoli residents were envisioned to have their lives and sanitation services improved by the ambitious “Greater Tripoli Basin WasteWater Networks” project by introducing an advanced wastewater treatment facility. This facility aimed to significantly reduce water pollution in Northern Lebanon, promising improved sanitation services for the region. Yet, two decades later, the project is far from realizing its intended objectives, marked by numerous stumbling blocks and the involvement of questionable contractors.

While the project funded by a loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB) was supposed to finalize all network connections to the treatment facility, the outbreak of the financial and political crisis in Lebanon in October 2019, put a hold on the 74 million euro loan. However, the agreement with the EIB included an 18 million euro grant, which is still available, as per EIB’s email to Daraj.

Progress, hurdles, and leading contractors

While delays have plagued the project, experts and key stakeholders interviewed during our investigation concur that the wastewater treatment plant represents one of the Mediterranean region’s most advanced facilities, as it covers the most advanced water treatment methods (up until the tertiary treatment) while having the capacity to generate its own electricity throughout the treatment process.

Despite these advancements, the plant’s actual operational capabilities remain minimal, conducting only basic treatment. This limitation arises from its failure to receive the required minimum wastewater capacity of 60 m3 due to the incomplete network connections, leading to a significant portion of wastewater being discharged into Tripoli’s Abu Ali River and the sea.

In an interview with Daraj, environmental expert and researcher Dr. Yasmin Jabli voiced concerns about the project’s management and planning: “In Lebanon, we are doing things backward. Instead of starting with the infrastructure and working in parallel on building the station and making the needed connections, we built the station first and then moved to networking.” She describes the plant today as a “bird sanctuary.” Dr. Monzer Hamze, also an environmental expert, echoed these concerns, questioning the logic of maintaining an expensive station while the shore and Abu Ali River continue to suffer from pollution: “It is not acceptable to wait for years for networking processes.”

To date, the station receives no more than 45 m3 of wastewater. However, with the resolution of connection issues in both the Koura and Qalamoun areas, wastewater volume is projected to reach the threshold needed for the station to function optimally, as confirmed by the EIB and the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) during their interviews with Daraj.

Who are the project’s leading contractors?

Suez did not respond to the request to comment.

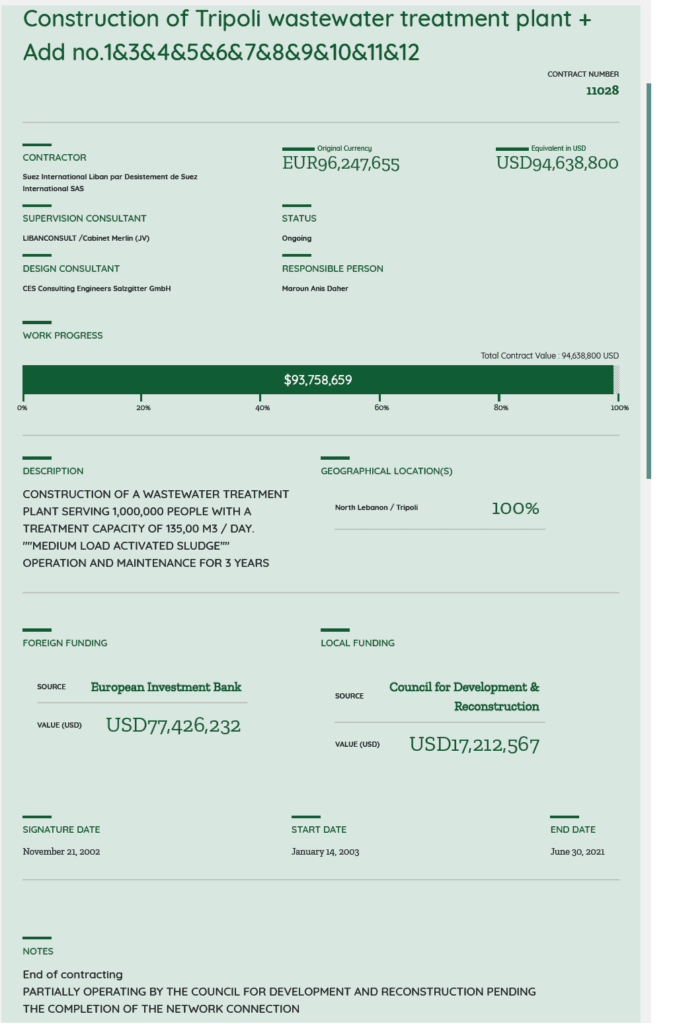

The facility itself was constructed by the French Suez Group, tasked with building a treatment plant serving 1 million people with a treatment capacity of 135,000 m3/day, as per its contract with CDR. The contract stipulates that the total amount is around 94.6 million USD with 77.4 million USD from the EIB and 17.2 million USD from the CDR, from a previous EIB loan that was approved in 1997.

Butec, a subsidiary of Suez Group, was contracted to build the sea outfall for the disposal of refined water to the sea from the treatment plant, as per the contract.

According to the CDR and the EIB, the treatment facility will reach the minimum capacity once the connections from Koura and Qalamoun regions, which had previously faced setbacks, are finalized.

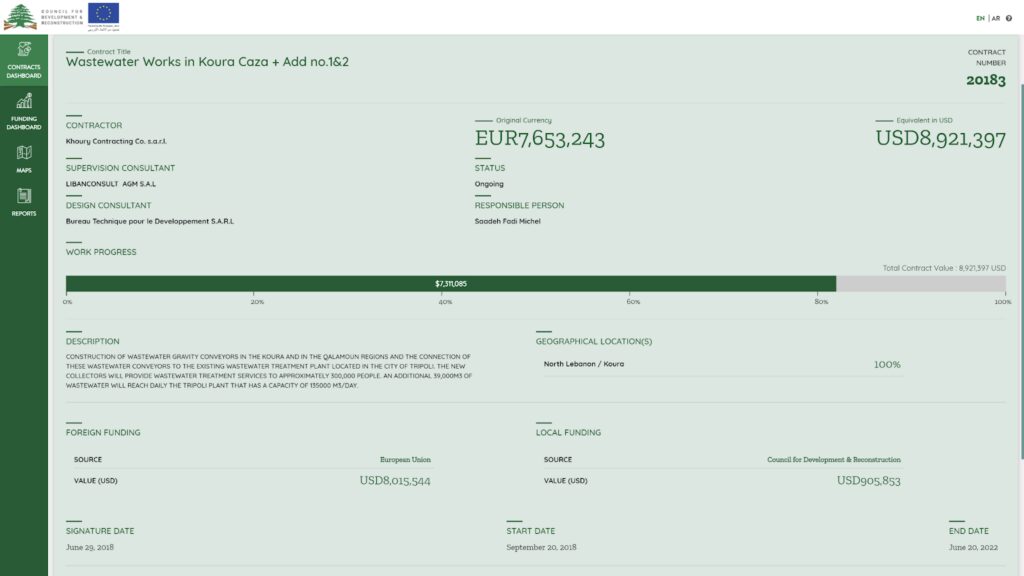

Koura Region: Following the termination of the contract with the Italian company Opere Pubbliche due to financial challenges, as per the CDR, the work is now being executed by Khoury Contracting Company, owned by Dany Khoury. Notably, Khoury has been under US sanctions since October 2021 “for contributing to the breakdown of the rule of law in Lebanon. Khoury is a close business associate of U.S.-sanctioned politician Gibran Bassil.” Accordingly, he has been “the recipient of large public contracts that have reaped him millions of dollars while failing to meaningfully fulfill the terms of those contracts. Khoury and his company have been accused of dumping toxic waste into the Mediterranean Sea, poisoning fisheries, and polluting Lebanon’s beaches, all while failing to remedy the garbage crisis,” according to the US Treasury Department.

The contract with Khoury Contracting, titled “Wastewater Works in Koura Caza,” aims to construct “wastewater gravity conveyors in the Koura and Qalamoun regions and the connection of these wastewater conveyors to the existing wastewater treatment plant” in Tripoli, as per the contract. The new collectors will provide wastewater treatment services to approximately 300,000 people and an additional 39,000 m3 of wastewater will reach the Tripoli plant on a daily basis, which has a capacity of 135,000 m3/day.

The EIB spokesperson confirms in an email that the EU has a complementary grant project in the Koura region for constructing sewage networks that will be connected to the Tripoli wastewater treatment plant with no EIB involvement. It was signed in 2018 with Khoury Contracting and is currently under implementation. After the US sanctions affected Khoury Contracting, an inquiry was launched by the EU Delegation in Lebanon to OLAF (European Anti Fraud Office) to check the charges mentioned by the US Treasury Department. The contract was suspended from December 2021 until February 2022 when “OLAF, after performing all due diligence checks, cleared the situation of the contractor and allowed the contract to resume.” The contract is worth around 9 million USD.

Khoury Contracting Company did not respond to the request for comment.

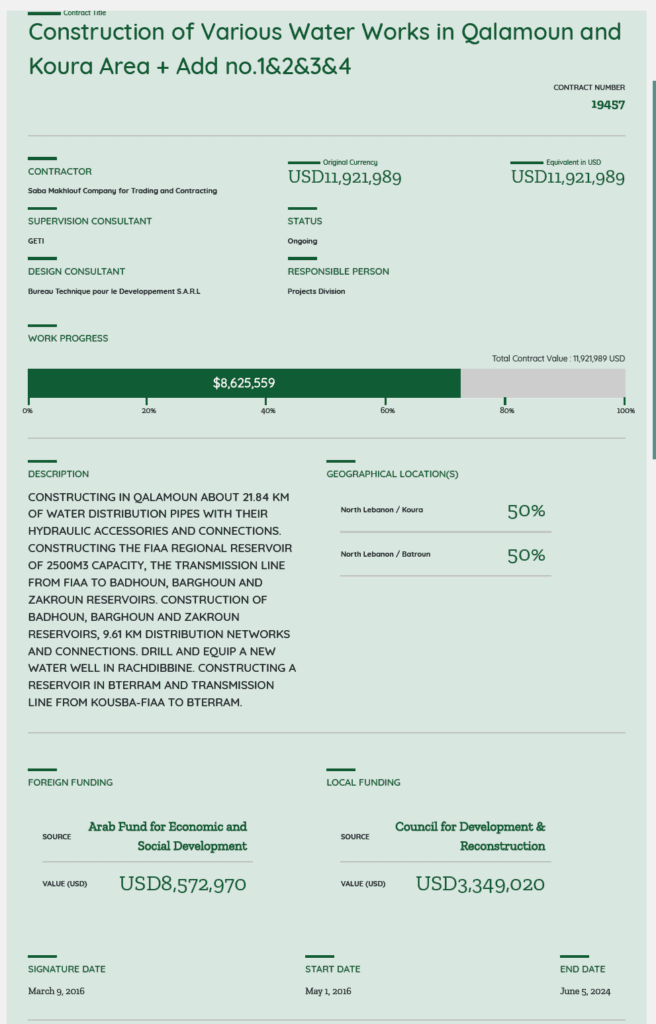

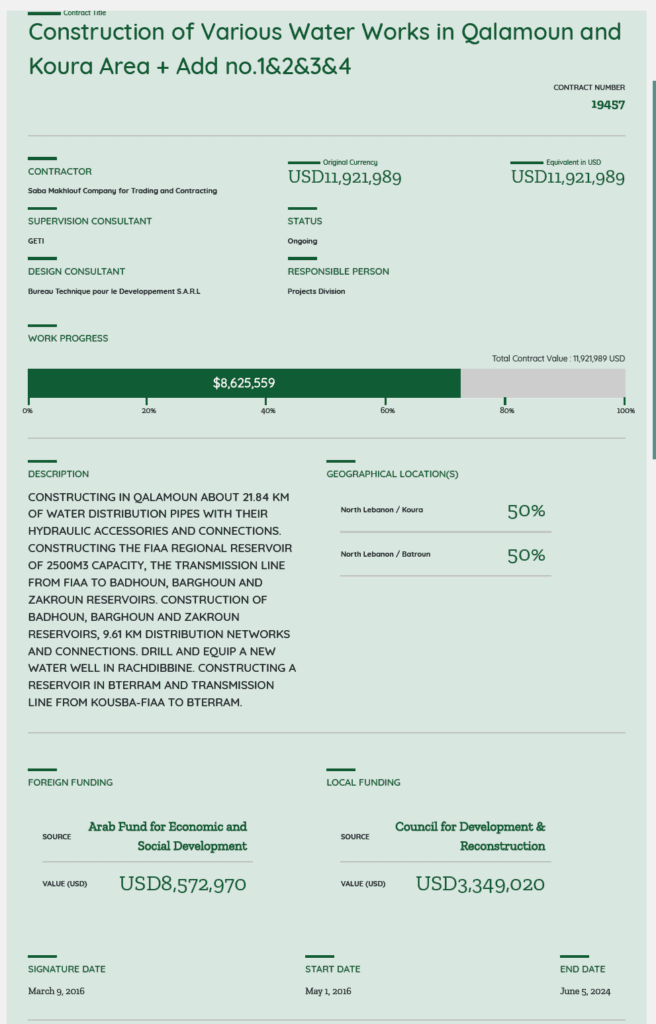

Qalamoun Region: The connections for the Qalamoun area faced delays as they were funded by the Arab Fund, which subsequently halted its funding after the Lebanese government failed to meet its obligations. However, according to the CDR, the situation is expected to be resolved soon with the Arab Fund’s involvement. The contracting company for the Qalamoun area is Saba Makhlouf for Trading and Contracting, responsible for constructing water distribution pipes, among other tasks, as per the contract, with a total of around 12 million USD.

Saba Makhlouf was also the contracting company for the sewage treatment plant south of Sidon, which “has not been operational since its launch in 2010, except for separating sludge from liquid, resulting in an annual cost of one million dollars to the contracting company Saba Makhlouf for Trading and Contracting, while its actual operational cost doesn’t exceed 250,000 dollars,” according to Al-Akhbar newspaper (2019). On the other hand, in 2019, Nidaa Al-Watan reported the appointment of seven employees from Saba Makhlouf’s company to state institutions without considering the financial crisis of distributing political favors and appeasing electoral voices.

Saba Makhlouf did not respond to the request for comment.

| Two studies conducted by The Policy Initiative (TPI), Resource allocation in power-sharing arrangements: evidence from Lebanon, and Cartels in Infrastructure Procurement: Evidence from Lebanon, examine 394 infrastructure procurement contracts awarded by Lebanon’s CDR from 2008 to 2018, a crucial player in the country’s infrastructure development. The findings reveal that politically connected contractors secured contracts inflated by approximately 34% compared to the average contract. Notably, these overpriced contracts, totaling around $160 million, occurred when both the designer and contractor had connections to influential elites. Moreover, projects designed by politically connected designers were more likely to experience overspending and larger cost overruns.“The mechanisms to share economic resources are based on informal arrangements, upheld by norms of power-sharing behaviors. According to the study, in the context of weak bureaucracies, such as the Lebanese’ bureaucracy, elites can penetrate institutions with loyal personnel to establish collusive networks.” |

While finalizing the Koura and Qalamoun networks might launch advanced treatment methods, the goal of cleaning up the Mediterranean Sea is yet to be achieved.

In the current situation, achieving that goal seems elusive as the second-largest city in Lebanon continues to face extreme poverty with the World Bank ranking Tripoli as the poorest city on the Mediterranean coast in 2019. Even after completing the connections for Koura and Qalamoun, not all the necessary connections would have been completed. As such, this will not put an end to the diversion of wastewater to the Abu Ali River and the Mediterranean Sea.

| Was Jihad Al Arab involved? Within Tripoli itself, some of the networks are completed, while others are not, due to the loan being put on hold. Sources say that a significant portion of the project was undertaken by contractor Jihad Al Arab, who is also under US sanctions. While Al Arab was awarded several contracts in diverse projects in Tripoli by the CDR, the European Investment Bank confirms that “Jihad Al Arab (who was sanctioned by OFAC in October 2021) does not appear as a contractor of the components financed by the EIB under the project Tripoli Wastewater. |

The CDR attests that given the country’s circumstances, building this plant was necessary. The cost of the plant today, excluding connections and infrastructure, would not be less than 170 million euros, meanwhile it was built along with the sea outfall for 100 million euros (excluding networks). According to the operating contract, the CDR is responsible for operating the plant only for three years. However, they have been operating it for about 8 years since the entity responsible for the operation, the Northern Water Establishment, is facing financial crises and does not have the capacity for takeover.

Project Background

In the second half of 2019, the EIB and the Lebanese government signed a

financing contract to support establishing a sewage network in the city of Tripoli and its surroundings.

Back in 1997, the EIB approved a project to build the facility itself. The project commenced in 2003 and ended in 2009 with both the plant and the sea outfall, which extend 1.6 km into the Mediterranean Sea, being constructed.

Throughout the project’s history, the suitability of Tripoli as the plant’s location has been a subject of frequent debate. This challenge isn’t unique to this project, as wastewater treatment plant siting often poses similar issues, according to the CDR.

Despite facing various setbacks, the project has been progressing slowly, yet its core objectives remain unfulfilled.

Project Funding

The total cost of completing the networking project is 107 million euros: this includes a 74 million euro EIB loan, an 18.3 million euro investment grant from the Economic Resilience Initiative Fund funded by contributions from several EU member states, and a second grant of 4 million euros as technical assistance. Thus the EIB’s contribution amounts to 92 million euros while the Lebanese government covers 10.7 million euros.

| Source | Amount |

| Self-financing | 10.7 million euros |

| Loan | 74 million euros |

| Investment grant from the Economic Resilience Initiative Fund, funded by contributions from several EU member states | 18.3 million euros |

| Technical assistance within the framework of the Economic Resilience Initiative portfolio managed by the bank and funded by the bank’s own resources | 4 million euros |

| Total | 107 million euros |

As mentioned earlier, the financial crisis that stormed Lebanon in October 2019 put the project and the loan on hold, yet the EIB is still committed to providing the grant, and the “EU has teamed up with UNICEF to finance operations and maintenance in the wastewater sector in the next 2 years with an envelope of nearly 30 million euros,” as per EIB’s email.

In an interview with Daraj, Minister of Environment Dr. Nasser Yassin expresses concerns about significant investments going underutilized, whether through aid, loans, or government treasury financing. He emphasizes that the station’s construction, costing nearly 100 million euros, lacked synchronization with the establishment of networks, indicating inadequate planning and coordination. As a result, many rivers and beaches remain polluted or receive lower priority for treatment.

Dr. Yassin attributes the issue to the absence of effective sewage sector management, emphasizing the sector’s critical impact on public health and safety, especially considering the Cholera outbreak last summer. The Council for Development and Reconstruction underscored the station’s significance during the outbreak, highlighting the potential catastrophe had it not been in operation.

Yassin believes that ” what we lack in Lebanon is proper management in Lebanon, especially in sewage management, not knowledge nor technology.” Both Yassin and the CDR affirm that the European Union is aware of the current situation and what the station lacks.

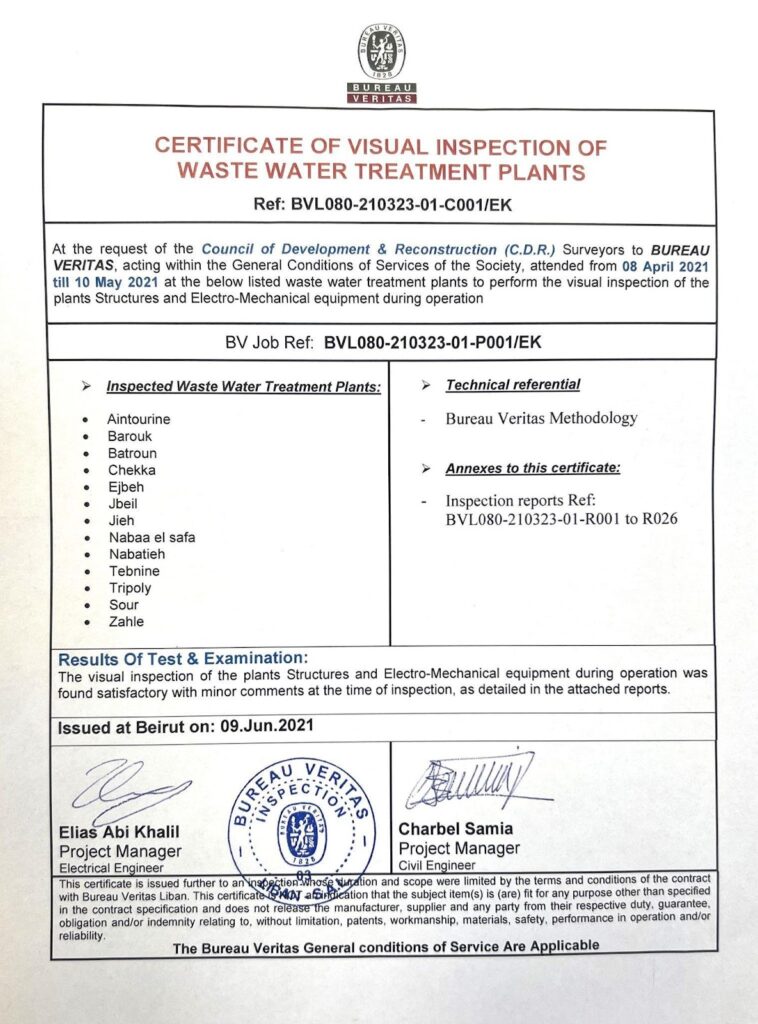

The CDR refers to a report by the international audit company Bureau Veritas on sewage treatment plants in Lebanon, including Tripoli, stating that they are satisfactory with only minor comments.

In conclusion, the “Greater Tripoli Basin WasteWater Networks” project, funded by the EIB, aimed to bring advanced wastewater treatment to Tripoli, benefiting nearly a million residents. However, this ambitious initiative has been marred by persistent challenges and setbacks, including the country’s financial crisis –which put the loan on hold, incomplete network connections, and questionable contractors. Despite having one of the Mediterranean region’s most advanced treatment plants, the project has yet to fulfill its intended objectives, while Tripoli’s residents continue to wait for slight improvements in their living conditions.

| Loan Process for Development Projects at the Council for Development and Reconstruction: 1. Project Planning 2. Preparation of a Technical Feasibility Study to assess the project’s feasibility. 3. Preparation of an Economic Feasibility Study to estimate the financial and economic aspects of the project. 4. Presentation of the project idea by the Finance Division at the Council for Development and Reconstruction to donor entities and financing funds. 5. Approval of the project by donor entities. 6. Negotiation of an agreement with donor entities. 7. Presentation of the project and approval by the Council of Ministers, including relevant ministers such as those of finance, public works, environment, interior, and others. 8. Initial signing of the agreement by the Prime Minister’s initials. 9. Approval by the Board of the Financing Fund for execution and specification of details. 10. Presentation of the final project formulation to the Council of Ministers to prepare a draft law for submission to the Lebanese Parliament. 11. Approval of the law by the Parliament (in the case of loans). 12. Conduction of detailed studies and preparation of tenders for project implementation. 13. Commencement of project execution based on approved details with local authorities and the lending entity. 14. Preparation of periodic reports and monitoring processes under the supervision of relevant authorities and missions from lenders or funders (Monitoring and Reporting). |