During the Egyptian Economic Conference held in October 2022, the Egyptian Prime Minister presented the economic problems that have been shaped by past policies and events, prompting the President to intervene, calling on the public to think about these issues. On the screen, a quote from the book The Personality of Egypt by Gamal Hamdan appeared, indicating that the Egyptian economy lacks adopting radical solutions and adheres only to moderate and soothing solutions that postpone crises rather than work to solve them.

The quoted passage was a critique of the Egyptian economic policies in the 1960s, which was not the subject of criticism alone among different political stages in Egypt. We used to hear the President of the Republic explaining to the people the extent of the disastrous policies from the 1960s and throughout his first terms and the challenges and difficulties faced by the regime at that time – and still faces.

Ten years ago, prior to the current economic crisis in Egypt, there were promises and a big promotional campaign, with the most important of promises being the restructuring of the social support system in Egypt, both in terms of its structure and its transformation into a digital and empowering structure, and in terms of its cohesion and the provision of a larger space of support for those eligible. But now, we are facing a severely deteriorating social support system, and the state does not pay attention to it at all, because it is concerned with selling more assets to compensate for the deficit in repaying debts.

Talking about the economic effects of past policies is still ongoing, and it peaked in a statement by Prime Minister Mustafa Madbouly, in which he blamed past economic policies for the current crisis of the youth and their inability to achieve their dreams under these circumstances. He also added that the Egyptian economy is currently struggling to overcome the effects of these crises, especially in terms of social policies.

Social policies are the support directed to citizens, through providing consumer goods and basic needs for living, either for free or at symbolic prices within reach of the poor, such as support for health, housing, and transportation.

Despite not providing anything for free, social policies and support mechanisms have undergone several transformations throughout the modern Egyptian economy, with stages of ascent and great expectations, descent, and devastating challenges. Therefore, they cannot be summed up in current government statements, which turn the matter into a polarized issue, suggesting that what preceded us was corrupt, and we bear the consequences of its policies.

Collective Problems by Necessity

At the forefront of Oxford’s definition of the welfare state, David Garland refers to the changes brought about by mass migration to cities, altering people’s lifestyles and distancing them from their small, local communities. Modern cities grew and created dense, new patterns of dependency, reflecting the problems of the poorest people onto those living better, making life truly collective. As a result, the problems and possible solutions have become necessarily collective as well.

The first intentions of having social policies in Egypt appeared at the time of Muhammad Ali’s project and the establishment of Egyptian capitalism independent from the Ottoman Caliphate. With this modernization project, social insurance for state workers emerged. Support policies remained fluctuating after Muhammad Ali and were not a priority for any ruler; they only appeared from time to time in the form of grants and gifts, limited to cities and not reaching villages and hamlets.

The book Free or Privatize? points to the beginnings of the rise of social support in the form of the spirit of cooperation and social partnership between the people and the institution. During World War II, the policy of rationing consumption began circulating widely, to save up resources sent to the army.

Egypt entered the realm of social support, fixed pricing for basic products was imposed, and work began on implementing the “rationing” policy, which then turned into a regulated decision in 1945. The state became a partner in solidarity, playing a social role in alleviating the burdens of living, as an exceptional case, given the suffering of Egyptian society from the cost of living. At that time, Egypt’s various resources were drained by the English occupation due to the war.

Social Welfare and the Nasserist State

Nasserist state socialism relied on social support as the basis for governance, meaning that it controlled the production process entirely and allowed itself supreme authority with a social dimension. The Nasserist era did not invent support but developed its nascent groundwork, expanding into nationalizing companies and setting prices for various consumer goods relied upon by the public, including transportation, food items, appliances, and even heavy industries.

Nasserist social support relied on employing the private sector to serve social policies, with the state acting as a regulator imposing fixed pricing on restaurant owners and limiting the amount an individual could consume. These concepts stemmed, firstly, from a comprehensive desire to engineer a new, independent, and stable society, while, on the other hand, fears arising from the repercussions of World War II persisted.

With the dawn of the sixties, the state’s objectives based on support and its expansion were translated through a broad nationalization campaign. This led to the inflation of the state’s economic role, with the emergence of public companies incorporating a package of small companies, serving a collective economic path defined by the state. These companies had their own activities and operational independence from the state in profit and loss accounts, but were subject to restrictions on price reductions and transferring surplus value to the state treasury. Conversely, these companies had the right to request support from the state when needed.

The foundation of the Nasserist support economy transformed the production process into a value with an initial advantage, namely, that the material provided in the market or traded was a material of utility value, with the state acting as a higher intermediary between it and the public to obtain it at a symbolic or free price. One of the most prominent examples of this path was the transformation in the electricity supply sector for citizens, especially in remote rural areas and hamlets.

Due to Egypt’s reliance on petroleum fuel, its cost was high, covering only 68 percent of the total electricity requirements within the country, as noted by Mohamed Jad in the research paper titled Welfare… From Generalization and Gratuitousness to Privatization. Therefore, Abdel Nasser decided to nationalize the Suez Canal and benefit from its resources to finance the High Dam and produce cheap electricity from a permanent source.

Electricity became available to suburbs and non-urban areas, opening up important informational and entertainment means, such as radio and later television, but these mechanisms were directed for political propaganda. Although the ambition to expand support was good, it lacked the logic of dealing with the state’s capabilities. With the resolution of the electricity problem, other problems emerged, such as neglecting the education sector, abundant investment capital not being utilized, and setting up an import-oriented market stimulating the local market.

On the other hand, the nationalization step was not confined to a revolutionary character only, because nationalization required the state to compensate company owners through bonds equal to the assets of the nationalized company. These bonds became a debt block on the state, which continued to swell in the face of the inability to repay. The idea of nationalization was linked to an expansion in the support system and providing welfare for the emerging middle class in the Nasserist state. However, the exclusivity of spending on welfare policies made the state limited to the circle of consumption only, with no productive alternative to achieve profit.

The Nasserist state insisted on the centrality of support to ensure the continuation of an important implicit contract, referred to in the book The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat: The Political Economy of the Two Regimes as the exchange of social rights for political rights, i.e., welfare and the right to support, in exchange for stripping the political right to opposition.

Under the Cloak of the New Economy

The centralized support model failed because it faced continuous financial pressure, and the tax system, in turn, was primitive and unable to access hidden wealth. Additionally, there were irregular economic and labor transactions that the state could not track, resulting in a loss of part of the wage tax to fund support policies.

Sadat quickly retreated from this structure in 1974, continuing the Nasserist state’s retreat before Abdel Nasser’s death. Nationalization became a financial burden that the state could not keep up with. In the early 1980s, consumer aspirations began to align with the new economic system, which called for austerity in social spending. The world, following the European side advocating for the state to abandon its paternal role, excluded the necessity of “support” from the context of state responsibilities, limiting the needy and the poor to a group seeking free money and services.

Due to their fragile economic foundations and loss of independence, developing countries were locally powerless and essentially resorted to external debt, making openness to the global economy a necessity. This is where lending institutions and support funds entered the framework of establishing “new reform plans.”

In his book The Strong System and the Weak State, researcher Samer Suleiman presents the evolution of reducing support directed towards societal segments. After the state’s retreat from the 1977 measures due to the student uprising, a lot of Gulf money flowed in 1980, with a portion of it employed in support policies. Spending on these policies in that year amounted to 20.1 percent of the state’s total budget but declined during Mubarak’s rule, reaching 4 percent in 2001.

The “Mubarak” Economy

There is currently a populist narrative that the people’s conditions before the January Revolution were much better, as people could make ends meet, with supplies and basic goods available in the market, and days passing by safely. This situation is attributed to general ignorance of economic policies, especially regarding support during Mubarak’s rule. The current difficulties in Egypt make people nostalgic for any previous period that seems easier, coupled with the political blame placed on the current regime for the January Revolution, considered one of the pillars of the Egyptian economy’s decline so far.

Mubarak completely broke away from the social support economy model, and during the years 1987-1996, he signed four financing agreements with the International Monetary Fund. The state began to promote the difficulty of welfare and the burden of support, as the beneficiaries were seen as lazy people who had not learned to plan, control their population, or seek employment opportunities provided by investment companies.

Mubarak’s regime managed the social support path profitably through concealment and gradualism, creating a governing authority that reduced the importance of any opposition attempt by directing support to state employees. This way, a bureaucracy was formed that provided support for the government. If not blessed, it would not object, out of fear for its “livelihood.”

Those eligible for support from state agencies were called “low-income earners,” and under this framework, many groups entered, receiving only diminishing scraps year after year. As long as there was a stable popular mass taking up a large portion of the meager support, representing the management of government institutions, there would be no effective opposition, no matter how bad things got.

Samer Suleiman coins a fundamental definition for the Mubarak era, which is the “institutional stagnation” based on arranging projects, announcing them to the public, and putting grand names on paper. However, real changes occurred internally, emptying these decisions of their content and making them meaningless and ineffective.

The State of Permanent Need

The Egyptian economy has not rid itself, since the Nasserist era, of the logic of the “subsistence” state that relies on receiving grants from other countries for containment and integration purposes, as the state’s economy relies on external support and aid. During Abdel Nasser’s rule, Egypt was the world’s leading recipient of Soviet aid, and during the Sadat and Mubarak eras, Egypt was the second-largest recipient of American aid.

The current Egyptian economic direction, in terms of support, is reflected in the repeated speeches of the president to the public on every occasion, with no permanent alternative to the necessity for us to mature, to deprive ourselves to build a strong state, and to endure and “go hungry” to take space on the map. This rhetorical activity represents a behavioral and regulatory role, evaluating the citizen’s performance based on his or her ability to bear burdens, ironically produced by government decisions.

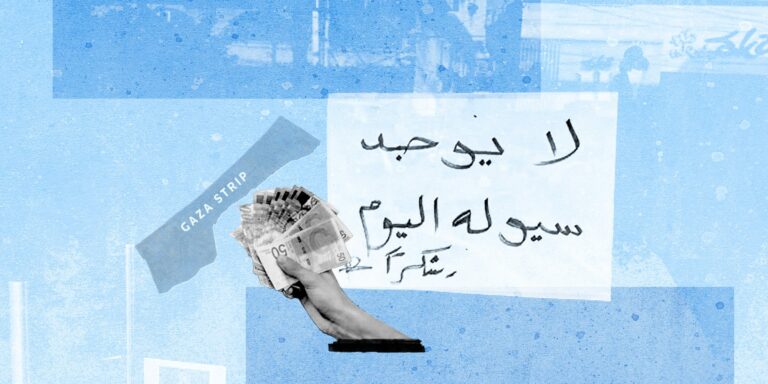

On the support side, perhaps the people are puzzled about what they should bear. In the supply sector, which represents the nerve center of feeding citizens, this system changed in 2014 under the guise of its digital restructuring to control the subsidy bill, reduce the leakage of goods to the market, and improve the level of service to citizens.

This new supply system resulted in fluctuations in the prices of subsidized goods. After the flotation of the pound in 2016, the state began to retreat in the face of the spread of goods in the free market, with the price of a liter of cooking oil reaching 19 pounds in 2019, the same pricing as in the free market.

The efficiency rate of the supply system decreased in 2022 in terms of its ability to cover a larger area, declining from 92 percent to 69 percent, while the costs of energy support decreased from 21.9 percent in 2012 to 1.03 percent in 2022. It should be noted that an increase in energy and fuel prices raises the value of all consumer goods circulated in the local market.

In the report From Support to Market? Privatization of the Supply System and the State’s Daily Transformations, Mary Fuentes indicates that the current supply system is undergoing a reduction in beneficiaries. The public has fallen under a formal freedom framework, where the displayed lists and choices do not satisfy consumption needs. On the other hand, the private sector, which should limit its role in this context as an alternative market, has become a system with wide access to an audience forced to consume these goods, thereby allowing for greater profit margins, as who will stop buying oil and sugar no matter how difficult the circumstances?

As part of the new economic paths in 2024 following the rescue of the Egyptian economy, formally through the sale of the Ras Al-Hekma area, the restructuring of the hospital sector support is being undertaken. The ticket price for morning clinics has been raised from one pound to 10 pounds, while the percentage of free treatment has decreased from 60 percent to only 25 percent. As a result of the recent circular, it is likely that the decision not to raise fuel prices will be reversed, especially diesel, due to its significant impact on inflation, while an increase in subsidized goods is expected following the depletion of the government’s stock of available items, as it will rely on purchasing the next batch at the new pound value.

The state’s abandonment of its role and neglect of its responsibility in support and the development of social policy allows greater opportunities for private investment sectors to buy assets and companies from the state, making basic consumer goods solely profit-driven and capital development and achieving further degradation of what remains of the middle class in this society. There is a class trying to rise up, freeing the state from its burden by relying on private education and consumer goods available to all in the market, with its relationship with the state limited to livelihood only. Meanwhile, the other side is saturated with a deserved resentment of the abundance of the feeling of need and the vast difference between the value of living materials and limited economic capacity, to disintegrate the “collective solution” element mentioned at the beginning of the article. For, problems are no longer collective, and there is no longer an obligatory form in the relationship between society and the state’s responsibility towards it.

Of course, the support policies in the Egyptian economy were not previously, in any stage, at their best, and perhaps the Mubarak era left particularly severe negative economic effects. However, at least under current trends, we are witnessing an unprecedented level of neglect of local support, increasing through continued ignorance of local economic needs entirely, in favor of unnecessary current trends and projects.

In conclusion, what we are witnessing now of people’s dependence on charity is not new, as President Mubarak, on the occasion of Labor Day on the first of May, delivered a speech ending with a meager bonus for state employees. And with every new economic crisis, supportive voices from the media and journalism are mobilized, consolidating the concept of the necessity of austerity and avoiding extravagance in food. And on one occasion of the Prophet’s birthday, Mubarak referred to the Prophet’s advice of hard work and avoiding extravagance, which will contribute to solving the economic problem.