| Episode One.

Angry crowds on their way to destroy the statue of Michel Aflaq and burn his office and library…

The rumor spread like wildfire, during one June morning, not much different from the other days of 2003: filled with anxiety, apprehension, and the unshakable feeling of waiting for the unknown. The news reached Kanan Makiya and Mustafa al-Kadhimi, in the midst of their work in the “Iraq Memory Foundation”, which was based in the house of the late architect Mohammad Makiya in the Karadat Mariam district in central Baghdad, and which Saddam’s regime had previously confiscated. Without much thought, Makiya and al-Kadhimi found themselves in a car speeding towards the spot, not far from their workplaces, trying to save whatever material could be saved. “It’s part of our work in the Iraq Memory Foundation; preserving all the remnants of the former regime, however cruel they might have been,” explained Makiya. “Who knows? Maybe when younger generations look at a statue of Aflaq and others that the foundation is trying to preserve, they may be reminded of that terrible history, and they would do their best to avoid repeating it. Maybe there is something in his library that would help us understand Aflaq’s mentality; what did he read? Did he leave comments on the margins of his books? Dozens of questions were going through my mind at that time.”

However, once they had arrived at the supposed site, everything seemed calm, no crowds, no destruction, and no burning. The site was guarded by seven US soldiers, led by a Lieutenant, it seemed to them from his uniform. The officer was surprised by the two men asking whether any Iraqi groups had approached the place in the last few hours, and the answer given was no, followed by questioning from the Lieutenant about the identity of the two men. With his clear English accent, Makiya introduced himself and his colleague, explaining to the Lieutenant about the rumor that had spread, and the nature of the NGO in which they worked and its interest in remembering the legacy of the former regime.

At this point, things took a surprising turn. The Lieutenant had a bachelor’s degree in history, and the two men had revived his passion for the topic, particularly because before their arrival he had seen a lot of files and documents, lying on the floor of the labyrinth of tunnels that lies beneath the building, which led to the Ba’th Party’s Regional Command offices, about 100 meters away in a separate building. The Lieutenant explained that a US troop had arrived a while ago, searching for something but he did not know what; perhaps sensitive documents, evidence on something, or a secret room in the walls containing something important. When they did not find what they wanted, they left. Without hesitation, Makiya asked to see those documents to answer the Lieutenant’s questions.

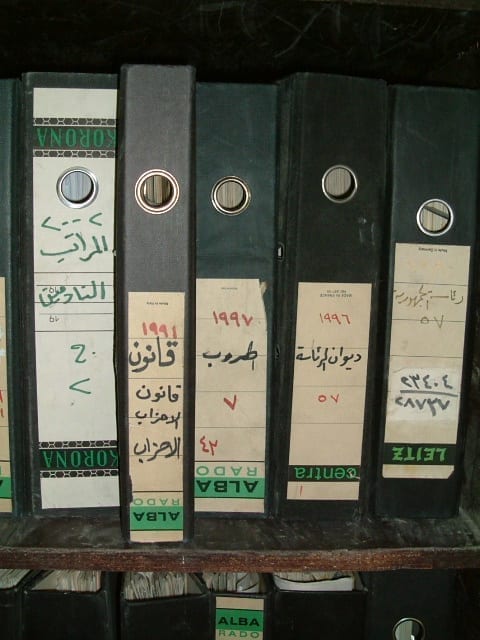

Moments later, the three were descending a dark staircase lit by a lamp held in the Lieutenant’s hands, toward the maze of dark tunnels, that smelled of moisture and mold. Thousands of files and papers were scattered all over the place; they had apparently been arranged on iron shelves that had been pulled down to the ground. Makiya took one corner of the tunnel while al-Kadhimi headed to another, and they both began exploring the files and papers in amazement.

Ba’ath Party documents as found by Kanan Makiya in the basement of the Regional Command building in Baghdad.

During their ongoing research, Makiya and al-Kadhimi were too busy diving in the documents to hear the Lieutenant’s questions: “What are these files? Are they important? Did you discover anything? Did you understand anything?” Finally, Makiya responded: “Yes. Yes… It is Aladdin’s Cave! This is the archive of the Regional Command Center of the Arab Ba’ath Socialist Party.”

A History Without Documents

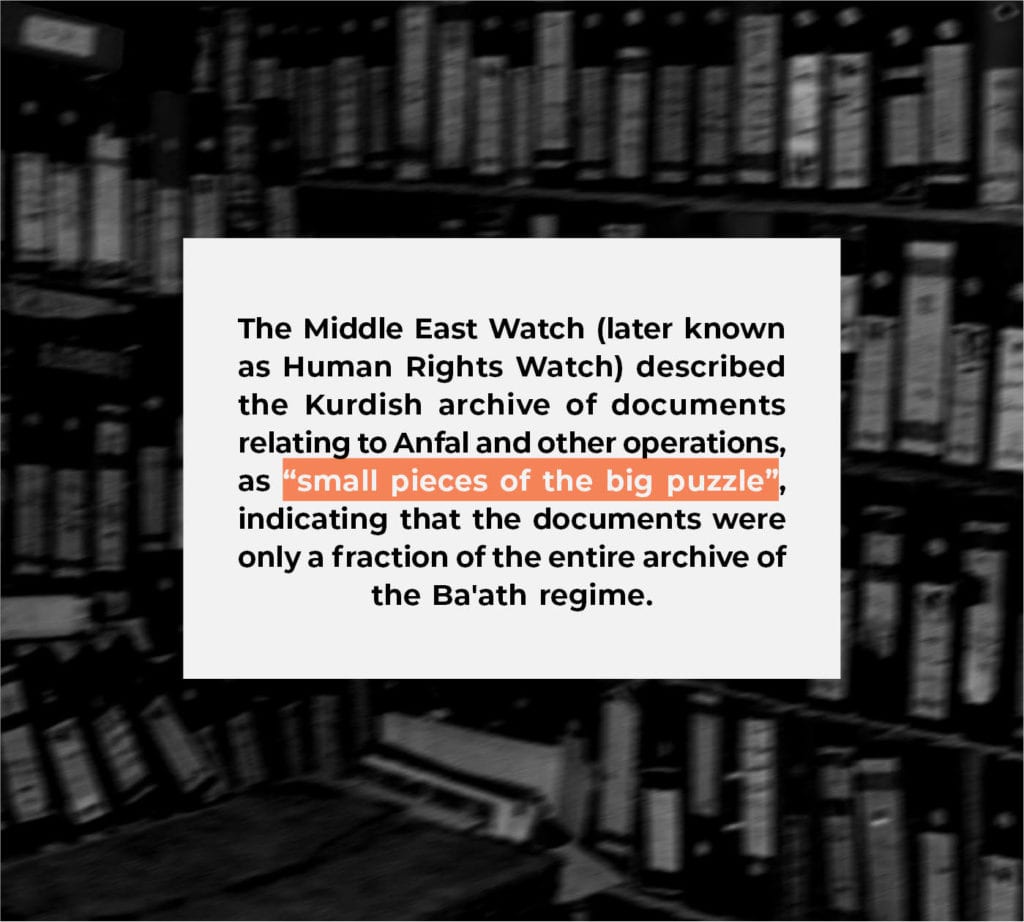

In an early report, the first of its kind, entitled the “Bureaucracy of Repression”, published in February 1994, the Middle East Watch (later known as the Human Rights Watch), described an archive of Kurdish documents during the Anfal campaigns and others, as “small pieces of the big puzzle”, in a reference to the fact that it was but a small part of the complete archive of the Ba’ath regime. Despite the enormous volume of documents found three decades ago, we cannot claim today that we have all the pieces of this so-called big puzzle, as we don’t exactly know how much of that was damaged, burnt, lost or hidden. Still, what emerged from this archive was enough to draw a clear picture of the stages that formed a fully fledged totalitarian regime, one that has continued to captivate the world’s attention, even after its demise. Before that, the history of Saddam’s regime remained undocumented until the 1990s; it was unknown, just like the history of other totalitarian regimes that controlled their countries with an iron fist. It was reminiscent of the history of ancient peoples in the prewriting era, in that it was almost a mere oral history based on tales, confessions, testimonies, rumors, and so on; these were the only documents left from those distant times for a historian to study. In 1991, what came to be known in the literature that studies Iraq after 1968 as the “Ba’ath archive”, emerged. The importance of this archive, then, is that finally history has a means of coming into existence through documented evidence coming from inside such regimes.

The First Category |

However, the absence of sound Arab writings that dig deep into the layers of hidden facts, have shrouded this particular archive with a thick cloud of ambiguity, opening the door to countless rumors and arguments that ended up gradually replacing the facts.

So, what is the Ba’ath Archive? What is it made up of? Who are the parties and NGO’s that seized it? Where is it now? Questions to which we have no clear answers, only articles scattered here and there, that do little to solve the riddle. The complete archive of Saddam’s regime includes dozens (if not hundreds) of millions of documents, photos, books, newspapers, artifact, film, audio, and artistic materials confiscated by dozens of entities on different occasions. The archive can generally be divided into two main sections, the first of which dates back to 1991 as we had mentioned, and includes documents obtained by Kurdish parties after the March 1991 uprising, as well as documents obtained by the US Army following the withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait in the same year. The second section concerns documents confiscated after the fall of the regime in 2003, from the US Army and many parties and NGO’s that will be mentioned later.

The Ba’th Party Regional Command Archive in the Iraq Memory Foundation

The Iraqi Memory Foundation’s share of the complete puzzle was limited to documents from the Ba’th Party’s Regional Command. In the weeks following the discovery of the archive, Kanan Makiya engaged in formal talks with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) to agree to transfer it to the offices of the Iraq Memory Foundation in Baghdad, with the goal of saving and archiving it, and this happened on September 23, 2003.

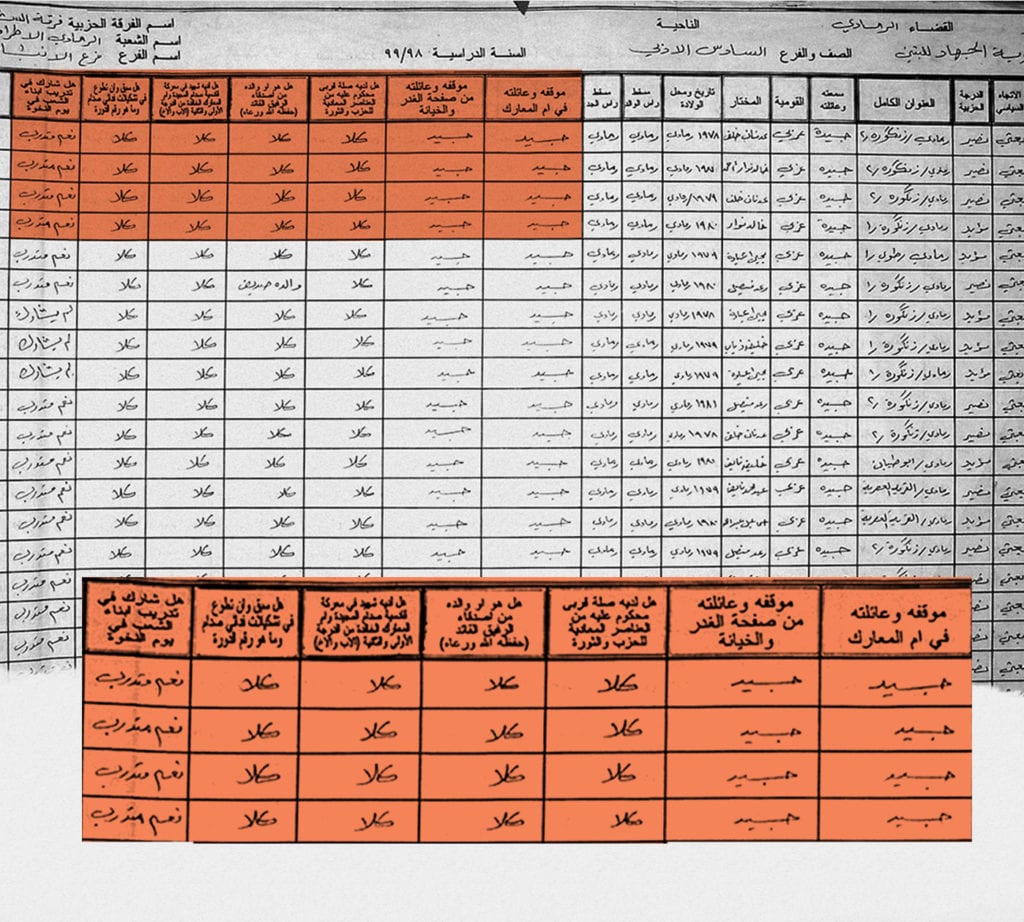

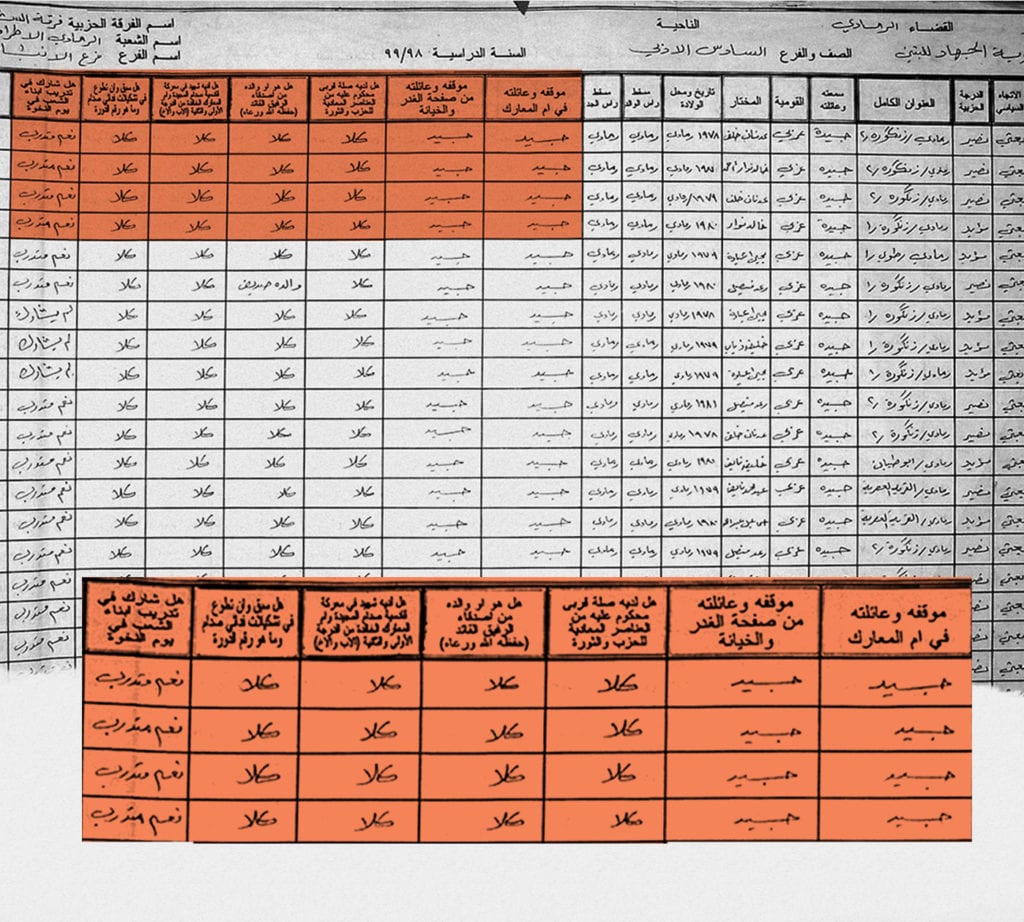

As soon as the foundation got a hold of these files, its team classified them into multiple categories, the first being the secondary school student’s data from Iraq’s 18 provinces. This category had a total of 160,000 pages of documents, with its digital copy holding around 160 GB, and focuses on the years after the 1991 war.

It includes the student’s name, date and place of birth, and the name of his parents, as well as his address, and political affiliation. There are also details about the student and his family’s political views on key events in Iraq’s recent history, including his family’s position on the Iraq-Iran war, opposition parties, the first Gulf War, and the 1991 uprising.

The Second Category | 2.7 Million Documents

The second category concerns correspondence between party headquarters in all Iraqi governorates, with about 2.7 million documents, and the volume of its high-quality images is around 5 TB. The most prominent letters that these pages documented include the correspondence of the Presidential Office with the security services such as intelligence, military intelligence and the Directorate of Public Security and Private Security. These files cover a wide range of topics in daily affairs and party-specific events.

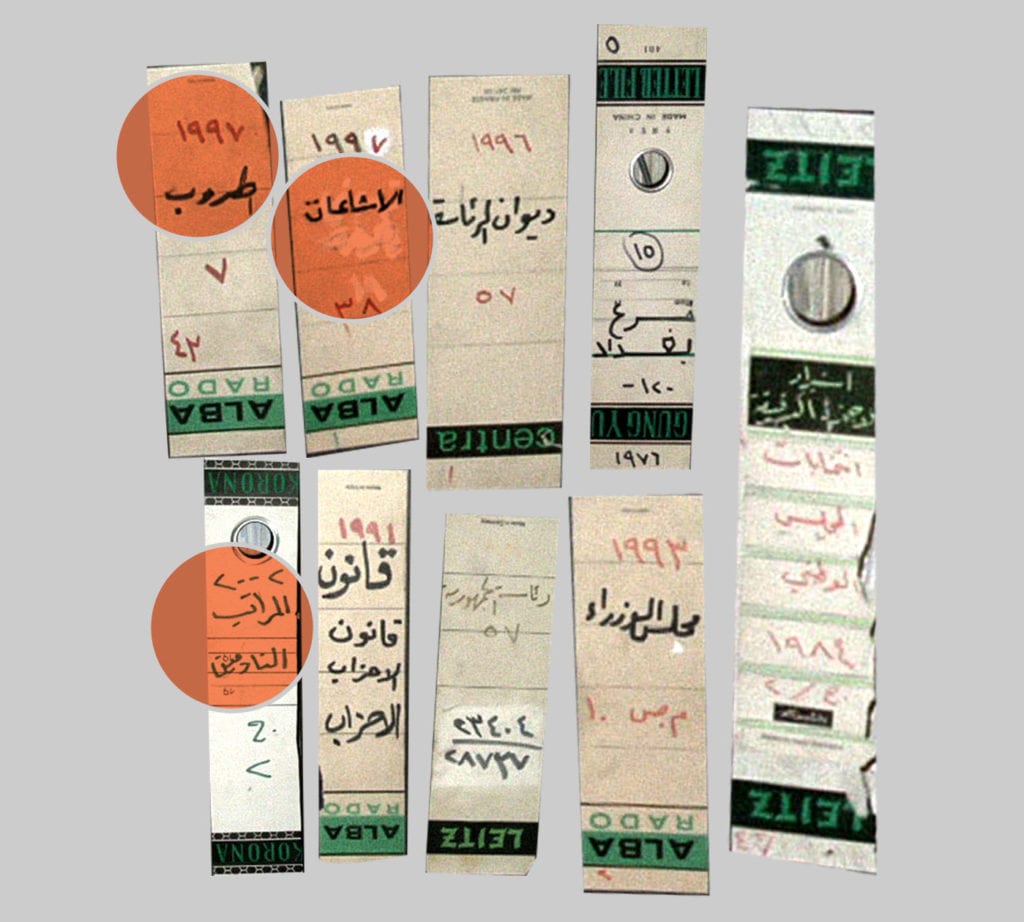

–The Third Category | More than 3 Million Pages

The third category is concerned with party membership files, with more than 3 million pages, scanned at a very high-resolution measuring about 5 TB. This category contains a file for all the party’s senior leaders, focusing on their security situation, their political functions, the recommendations of their leaders and officials regarding their promotions at work and their role in securing party interests in their areas of residence and employment, in addition to other details such as travel requests and retirement procedures. There are also files for some of the party’s second line leaders, and some members who were not leaders but experienced various problems, such as dismissal from the party.

The Fourth Category | 1.336 Pages

The fourth category concerns the 1,336-page files of the Ministry of Culture and Information. This category consists of documents specific to the said ministry, which give an adequate idea of Saddam Hussein’s obsession with his image before the public, covering the period of 1991-2003.

This category includes Saddam’s texts that mimic the Quran in style, and others related to Iraqi culture, negatively or positively, including a clear desire to reshape it and its many branches, such as in poetry and architecture, for example, and to sketch a platform for what the Iraqis called the national media, to correspond with Saddam’s imagination and taste.

–There is also a collection of belongings, like medals, as well as torn photographs and documents that have been partially damaged by moisture. The VHS video library and audio files created by various departments, government agencies and individuals affiliated with the Ba’ath Party contained various sections of news reports, documentaries, and music. Other files show Saddam’s speeches, the party’s women organization meetings, and party events held by Uday Saddam Hussein, and so on. There is also a small file on the Jewish presence in Iraq, which provides an inventory of Jewish families and their members, as well as families that have changed their religion to Islam or Christianity, with a focus on the Kurdish provinces.

Finally, there are “secondary files” that began to be collected in 2004, after various entities were trying to get rid of them by any means, for lack of ways of making use of them. Here, the Iraq Memory Foundation has been involved in collecting and protecting those documents, through a local network of mediators who have learned about the organization’s activity in safeguarding documents from the Ba’ath era. The total number of secondary files is estimated at 200,000, with a volume of about 50 GB of the high-resolution image version.

The Controversy over the Transfer to Hoover

In November 2004, Human Rights Watch published a detailed report, entitled “Iraq: State of Evidence,” by the human rights activist, Hania Mufti, in which she revealed the identities of the authorities who took possession of parts of Saddam’s archive. Along with the US army, there were the Iraqi National Congress, the Kurdistan Democratic Party, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, the Iraqi National Accord, the Iraqi Communist Party, and the Islamic Dawa Party. As for the NGOs, there were the Iraq Memory Foundation, the Free Prisoners Association of Iraq, and the Political Prisoners Foundation (Iraq), to name a few.

Today, the fate of the original documents in the archive, the ones that Mufti mentions in her article, is unknown. Where are they? What is in them? And how large are they? Indeed, researchers have been facing a complete blank regarding such questions, and we do not know what authority we could turn to for help to gather such information. Fortunately, the Iraq Memory Foundation’s archive has been the one exception to this general rule, and that is only because they have made their information accessible to all researchers. It is worth noting that dozens of books, studies, and articles have been published, based completely on information from the Ba’th Party Regional Command Archive, along with a plethora of explanatory statements that were made by those who are responsible, for whoever may need them. However, this archive, that was entrusted to the Iraq Memory Foundation, faced a major problem in 2005, due to several factors, beginning with, “the tension of the security situation in Baghdad, the targeting of the Foundation headquarters with Katyusha rockets more than once, and the threats of physical liquidation its workers had received,” according to Makiya. This was coupled with the slow workflow owing to the funding drying up and the limited capabilities of the accessible scanning devices in Baghdad. In other words, the main mission of the Iraq Memory Foundation, which is to preserve and secure the archive, was now at stake. This prompted those in charge of the Foundation to consider another safe haven that guarantees the safeguarding and persevering of the archive, and to accelerate the making of an inventory, classification, and scanning of the documents. Makiya continued explaining, “We reached an agreement with the US Department of Defense through Paul Wolfowitz to transfer the great part of the unfinished archive to the USA to be scanned, and entrusted afterward temporarily to the Hoover Institution pending its return to Iraq, while the already scanned and archived part remained in Baghdad,” which was later received by the Iraqi government in April 2009.

This transfer left the archive vulnerable to attacks by many parties inside and outside Iraq, who launched a smear campaign on the Iraq Memory Foundation, involving accusations of plundering Iraqi archives. This smear campaign did not stop until the Iraq Memory Foundation mediated to sign a new “Memorandum of Understanding” between the Government of Iraq and Hoover, in which the Iraqi government would replace the Memory Foundation, for purposes of following up all matters concerning the archive now entrusted to the Hoover Institution on a temporary basis. It is worth mentioning that the Memorandum was signed as far back as 2012.

Today, the fate of the original documents in the archive, the ones that Mufti mentions in her article, is unknown.

Where are they? What is in them? And how large are they?

This transfer left the archive vulnerable to attacks by many parties inside and outside Iraq, who launched a smear campaign on the Iraq Memory Foundation, involving accusations of plundering Iraqi archives. This smear campaign did not stop until the Iraq Memory Foundation mediated to sign a new “Memorandum of Understanding” between the Government of Iraq and Hoover, in which the Iraqi government would replace the Memory Foundation, for purposes of following up all matters concerning the archive now entrusted to the Hoover Institution on a temporary basis. It is worth mentioning that the Memorandum was signed as far back as 2012.

Moreover, an examination of the official letters and books provided to us by the Memory Foundation revealed that it had never excluded the concerned governmental parties in its negotiations about the future of the Archive, even though the full reins were in the hands of the Coalition Provisional Authority, at the time of the Governing Council and before the formation of the first Iraqi government. Makiya asserted that the late politician “Ahmed al-Chalabi, was one of the first people who approved the supporting of the Iraq Memory Foundation efforts when he was at the helm of the Governing Council,” referring to the Governing Council Resolution No. 336 dated March 28, 2004. The booklet entitled “History of the Iraq Memory Foundation documents,” issued by the Foundation itself, mentioned all the concluded agreements with the Iraqi government, in addition to the mutual official correspondence between the two parties, documented with pictures.

On August 25, 2004, the then Iraqi Prime Minister Iyad Allawi gave his approval to the Iraq Memory Foundation to carry out the documenting mission of the Ba’th Regional Command Archive, upon transferring it from the trusteeship of the Coalition Provisional Authority. On September 17, 2007, the Memory Foundation received a copy of an official letter issued in English by the Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s office, in which they expressed their support of the agreement concluded between Iraq Memory Foundation and the Hoover Institution, and urging the US institutions to help in completing this mission. In the same month, the Iraqi President in-office Barham Salih, who was then the Deputy Prime Minister, sent a message to the American institutions expressing the government’s appreciation of the Iraq Memory Foundation efforts, and calling on them to spare no effort to preserve the archive entrusted to the Hoover Institution.

Soon, the “Accountability and Justice Law” was issued on January 14, 2008, which included a paragraph indicating the establishment of a permanent Iraqi archive under the Iraqi law, which all the Baʽth Party documents will be entrusted to. The Iraq Memory Foundation then requested a “Statement of Guidance” from the Maliki government regarding the legal status of the Ba’th Regional Command archive. When the legal advisers in the Prime Minister’s office reviewed the request’s content and main elements, their response was to support the Foundation to proceed its work, and to back its Agreement with the Hoover Institution, in order to preserve and restore the documents, provided that the archive would be returned to Iraq once the aforementioned Agreement has expired.

In light of the controversy raised by the Ministry of Culture that included criticism of the procedures that were taken to transfer the archive to the Hoover Institute, the Iraq Memory Foundation requested another “Statement of Guidance” about its legal position from the ministry itself. On April 24, 2008, the foundation received a letter signed by Jaber al-Jabery, the former deputy minister, that stated in its preamble all the decisions and the official letters which proved the foundation’s firm legal position. Al-Jabery concluded that the Ministry of Culture “recognizes, supports, and considers the efforts exerted by the Iraq Memory Foundation a crucial part of the ongoing national Iraqi quest for liberating Iraq from the remnants of the previous regime, especially by preserving and scientifically taking care of the documentary heritage and preparing it for providing the general usefulness required under the laws.” He also requested from “all the services concerned to cooperate with the foundation (Iraq Memory Foundation) to achieve this national goal.”

Three days after the previously mentioned letter, al-Jabery sent a letter in English to the international institutions, namely the Society of American Archivists and the Association of Canadian Archivists, which issued a statement calling for the Hoover Institute to return the archive deposited with it to the Iraqi National Library and Archives as the relevant Iraqi entity. In his letter, al-Jabery confirmed that the Iraqi government had been previously briefed on the steps taken by the Iraqi Memory Foundation regarding the documents deposited with Hoover Institute, and approved that deposit agreement. He explained that the Iraqi National Library and Archives, one of the institutions of the Ministry of Culture, will not be the final repository of those documents once they return to the homeland, according to the Justice and Accountability Law, that stipulates establishing a separate permanent Iraqi archive for the documents of the previous regime.

In this regard, Ali al-Dabbagh, the Iraqi government official spokesman, sent a letter to the two prestigious archives institutions on May 1, 2008. In his letter, al-Dabbagh commented on their statement and emphasized that the responsibility of defining the appropriate agency for preserving and utilizing the documentary material of the previous ruling regime is limited to the Iraqi government, according to the Iraqi law. He added that the activity of the Iraqi Memory Foundation, which is performed under the continuous provision of the Iraqi government, falls within the national efforts for achieving the common good. Also, the Iraqi government had previously considered and approved the temporary deposit done by the Iraqi Memory Foundation with the Hoover Institute. Thus, including this group of documents in the list of the five groups that the statement issued by the two institutions asked to be returned to Iraq, is not warranted. After thanking the two international institutions, al-Dabbagh invited them to coordinate with the Iraqi Memory Foundation, which has been calling for the return of the mentioned groups and others.

However, all those agreements were not enough to end the international and Iraqi controversy, a controversy which continued to ignore the formal agreements concluded between the Iraq Memory Foundation and the Iraqi government. It continued to be argued that those conventions violated the Iraqi law and the relevant international laws and conventions, and they made the claim that they were arrived at by Iraqi officials ignorant of the law and new to politics. The controversy continued amid confirmations of senior governmental parties who have consistently emphasized the firm legal position of the Iraq Memory Foundation and that it submitted all the documents it got to the Iraqi government in Baghdad. The controversy kept going on until February 2012, when Falih al-Fayyadh, the advisor of the National Security Council representing the Iraqi government, signed a detailed Memorandum of Understanding with Richard Sosa, head of library and archive of the Hoover Institute. Under this agreement, the supervisory powers over the archive were transferred from the Iraqi Memory Foundation to the Iraqi government. The two parties of the agreement confirmed that a group of the Iraqi documentary material deposited with the Hoover Institute belongs to the Iraqi people represented by the elected government according to the constitution. Subsequently, the final decision regarding dealing with this group of documents is solely up to the Iraqi government, while adopting Hoover Institution as an external center for depositing Iraqi documents, as agreed upon by both parties.

“My dream was that the course of the Iraqi and Middle Eastern studies would change as soon as the nature of the Ba’th Regional Command Centre Archive was made available. After all, this is what had happened to Soviet studies with the appearance of the Smolensk Communist party archive at Harvard University, even though the Smolensk archive amounted to less than 10% of the one we had preserved.

Kanan Makiya

This is how the Iraq Memory Foundation acquitted itself over the issue of the transfer of Iraqi documents to the Hoover archive. However, Makiya and his colleagues at the Iraq Memory Foundation continued to trace the numerous books, studies and articles that were based on the archive of their foundation. They continue to answer dozens of questions raised by scholars, students, and journalists to date.

“My dream was that the course of the Iraqi and Middle Eastern studies would change as soon as the nature of the Ba’th Regional Command Centre Archive was made available. After all, this is what had happened to Soviet studies with the appearance of the Smolensk Communist party archive at Harvard University, even though the Smolensk archive amounted to less than 10% of the one we had preserved. I dreamt that every family that had lost a loved one would be able to visit such a public database as the Iraq Memory Foundation had dreamed of building in order know all information relevant to the deceased at just the click of a button,” Makiya said, “We played a role in providing a temporary safe haven for the archive, thanks to the professional team which worked on that aim for many long years through which we preserved each and every piece of paper and kept careful track of its origins and provenance. Now here we are, the Iraq Memory Foundation and Hoover Institute, keeping our promise to the Iraqi people, and returning the full collection to Baghdad. It’s on the way back to its homeland, where it belongs,” He concluded.

–