This investigation was carried out with the support of “Skeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedoms“

Corruption has turned the Litani River, Lebanon’s main artery, into a cancerous curse that has left no home or family on its banks untouched. As the people living along the river are fighting the pollution and disease penetrating their homes, time to implement the Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project (LQPPP) is running out.

Meanwhile, Lake Qaraoun, the artificial lake in the Bekaa Valley created by the Litani River, continues to be polluted before their very eyes. There has been no tangible improvement in water quality in recent years. It appears companies and contractors allied to the parties in power are the only ones to have benefited from the World Bank loan for the project.

They include contractor Dani Khoury, who is closely linked to the head of the Free Patriotic Movement Gibran Bassil and has recently been subjected to US sanctions. Another contractor, Mohamed Danach, is affiliated with Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri.

The $55 million World Bank loan to implement the project aimed at reducing the discharge of untreated sewage into the river and improving pollution in and around Lake Qaraoun has been in place since 2016. But the project’s closing date is June 30, 2023. And so far, nothing has changed for the better …

Cancer Rules

Years of pollution have caused a human and environmental tragedy in a region the inhabitants refer to as “the dumpster.”

According to Ziad Chehab, a man in his fifties, the Lebanese state has committed “genocide” using “biological warfare with contaminated water.”

Chehab’s mother has bone cancer. His wife has breast cancer.

Cancer is not the exception but the rule in the region. The disease has become widespread among all age groups. Chehab’s wife’s nephew, who is only ten years old, is suffering from a terminal illness and undergoing treatment.

In Bar Elias, a town of some 40,000 people east of Zahlé, the same story is repeated over and over again.

“The Litani River has become a sewer,” said Qassem Al-Hayek, a man in his fifties. “In Bar Elias not a day passes without mourning someone who died of cancer.”

Billions of Dollars with Minimal Impact

A lot of money has been pumped into Lebanese sanitation projects over the past few decades. In terms of endowments, it is the country’s second-largest sector with a value of nearly $1.5 billion, which does not include amounts allocated as loans, according to the Gherbal website.

However, improvements made by such sanitation projects are rather small and do not live up to the large amounts of allocated money. The biggest beneficiaries are generally companies, contractors and consultants.

Most of the money has been wasted, as it failed to provide any sustainable solution to fight the widespread pollution. Meanwhile, it only increased the financial burden that weighs heavy upon Lebanon and the Lebanese. Nevertheless, international financers are still passing contracts and projects to consultants and contractors linked to politicians who have long been suspected of corruption.

“The main problem is that private interests are prioritized over the public interest,” Dr. Sami Alawieh, Director General of the Litani River Authority (LRA) told Daraj.

This may take the form of contractors and consultants prolonging the project to the extent of depleting its operating expenses. Another reason for projects failing is a lack of urge and responsibility on the part of the authorities concerned.

So far, only Danny Khoury has been placed on the US sanctions list. In 2020 alone, his company received more than $615,000 from the WB project’s loan.

Project & Loan

The World Bank approved the Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project on July 14, 2016. The $55 million loan agreement was ratified and published on the official gazette on September 12, 2016. Yet, while the project’s end date is set at June 30, 2023, work on the project is still in its infancy.

| Agreement date | Project end date | Loan amount | Paid to date | Interest and costs |

| 12 September 2016 | 30 June 2023 | $55 million | $9.62 million | $2.01 million |

The project’s main pillars are:

(1) Improving domestic sewage collection

$50.5 million

Supporting the expansion and rehabilitation of the sewage network in: A – The vicinity of the city of Zahle to connect it with the sewage treatment plant in Zahle

B – The vicinity of the city of Anjar to connect it with the sewage treatment plant in Anjar

C – In the vicinity of the city of Aitanit, to connect it with the sewage treatment plant in Aitanit.

(2) Promoting sound agricultural practices

$1.5 million

Encouraging the “use of sustainable production systems among farmers in the upper Litani Basin.”

A – Evaluation of current agricultural practices

B – Developing a Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) program

C – Training stakeholders on how to implement the program

(3) Solid waste management, water quality control, capacity building and project management

$3 million

Providing technical assistance to:

A – Ministry of Environment

B – Litani River Authority

C – Bekaa Water Corporation

D – Ministry of Energy and Water

According to the loan agreement signed by the Lebanese state and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which is administered by the World Bank, the total cost of the project is $60 million.

| Source | Amount (million dollars) |

| Self-financing | 5 |

| A loan from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development | 55 |

| Total | 60 |

According to the latest World Bank interim report on the project, which was released in September 2021, it is showing only slow progress.

By the end of 2020, only $9.62 million had been paid out, while the project has been running for over five years, which is over two-third of the project’s timespan.

The Challenges

“When the project was signed, it aimed to dilute about 60% of the sewage reaching Lake Qaraoun,” said head of the LRA Sami Alawieh. “This project stumbled alongside the stumble of other parallel projects related to the wastewater treatment stations.” Consequently, and with several stumbling projects, “spending is increasing and sewage is increasing,” to the extent that Alawieh considered that “there is a process of extermination, biological warfare with sewage against the people of the central Bekaa, Baalbek-Hermel, and some western Bekaa.”

In an interview with Daraj, Dr. Walid Safi, Government Commissioner of the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) (until his retirement on February 11, 2022), gave several reasons for the delay in implementing the project.

Most notably, he mentioned the successive crises in Lebanon, starting with the collapse of the national currency and economic crisis in October 2019, the recent amendment by banks to the execution warranties (in lollars instead of dollars), the Covid pandemic and the Beirut port explosion.

This is in addition to incomplete acquisitions of land, especially after the expropriation judge retired and did not appoint a replacement. The latter was confirmed by Alawieh.

However, all these factors date back to 2019 or later, i.e. several years after the project was inaugurated.

One of the main obstacles the project faced after its launch was the difference between the preliminary studies, on the basis of which the number of kilometers and areas for the sewerage system was determined, and the reality on the ground, which showed greater lengths and additional areas.

It is necessary to extend sewerage networks for the project to achieve its goals, according to Safi, who also mentioned the project had already failed in an earlier period, which resulted in a change of teams working on the project. The latter has been cited as another reason for the delay in its implementation.

For his part, Alawieh believes that the main reason for the project’s failure is mismanagement by the CDR, as well as some parties in the World Bank and the Ministry of Energy and Water. According to the loan agreement, the Lebanese state is obliged to repay 6.67% of the loan on every April 15 and October 15, starting October 15, 2022. In other words, Lebanon would have to pay back $3.67 million later this year, but the issue has not yet been discussed with the World Bank, according to Safi.

The author of this investigation contacted the World Bank with questions about the project, but did not receive a response before publication. The project has three refining stations: Zahle, Anjar and Aitanit. For each station, according to Safi, the sewage network is to be expanded, so that the plant can function properly.

He emphasized the importance of working in an integrated manner, as only a few areas have adequate sewage networks and infrastructure. He furthermore stressed the need to build and/or repair all sewage networks in all areas near the Litani, the upper basin of which extends over an area of 1,500 square kilometer. It includes 99 towns distributed over the administrative regions of Baalbek, Zahle, West Bekaa, Rashaya.

However, the current loan should be seen as but one stage in the process, as it does not cover the cost of extending sewage networks in the entire region. It is necessary to extend sewerage networks for the project to achieve its goals, according to Safi, who also mentioned the project had already failed in an earlier period, which resulted in a change of teams working on the project. The latter has been cited as another reason for the delay in its implementation.

How does the World Bank Deal with Suspicions of Corruption?

The World Bank states in its report of September 2021 that the main risks facing the project since its inception have been politics and good governance. But how does the bank confront such risks?

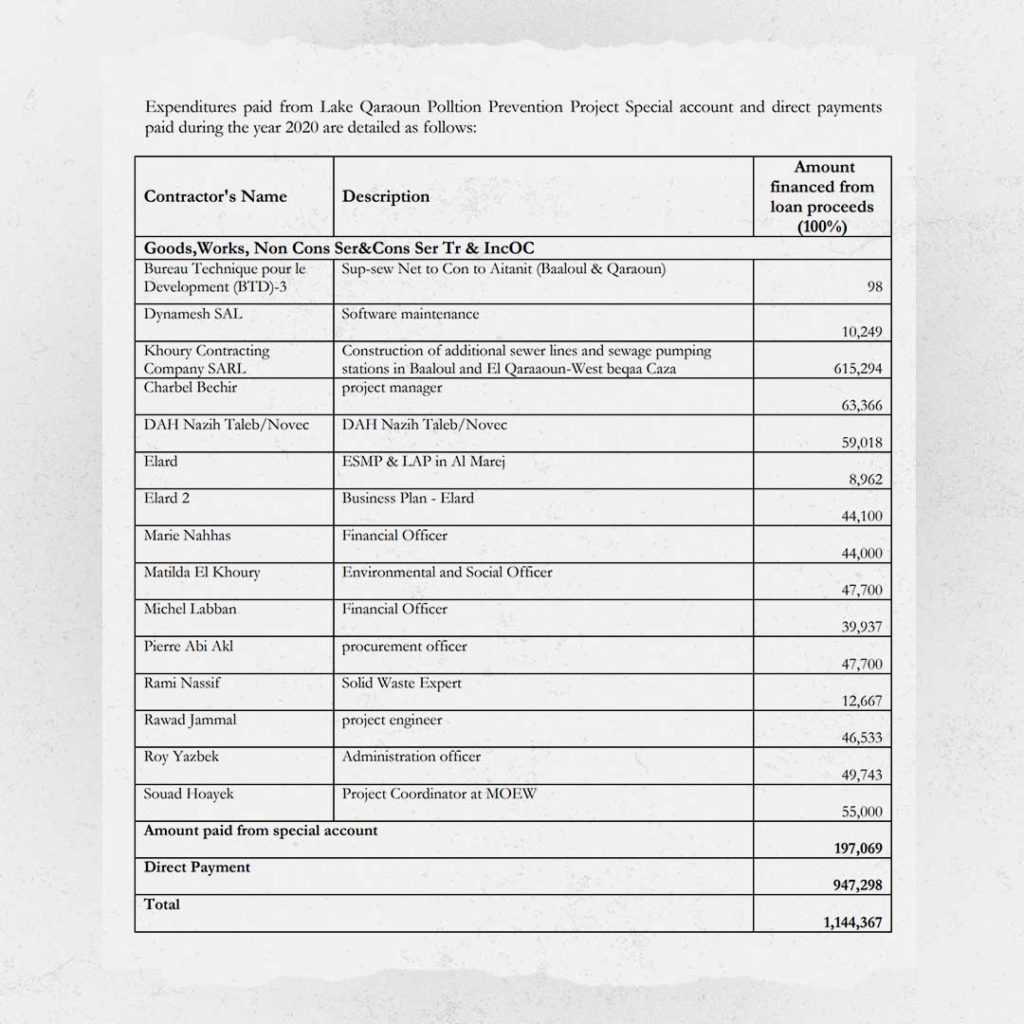

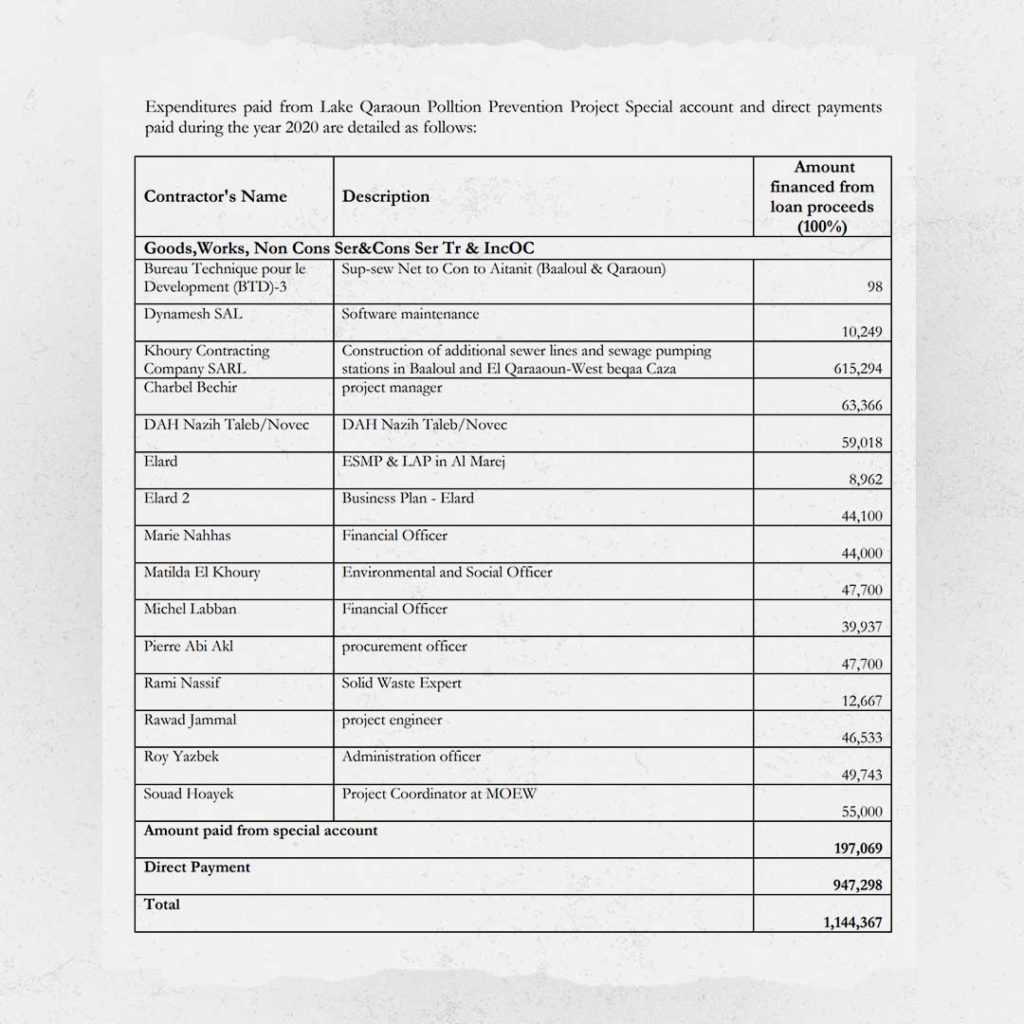

The last financial audit on the project issued on December 31, 2020 shows that the following companies received the following amounts: Note that the project had failed in an earlier period and that the project management team was changed. Therefore, some of the names mentioned in the document are no longer part of the project.

Among the most prominent companies benefiting from the project are:

Khoury Contracting Company

Danny Khoury is a businessman close to Gebran Bassil, who on October 28, 2021, was placed on the US sanctions list for “contributing to the collapse of the rule of law in Lebanon.”

“Because of his close relationship with Bassil, Khoury obtained significant public contracts that brought him millions of dollars while failing to purposefully fulfill the terms of those contracts,” reads the US Treasury statement. “In 2016, Khoury was the recipient of a contract worth $142 million from the CDR to operate the Bourj Hammoud landfill. Khoury and his company have been accused of dumping toxic waste and refuse into the Mediterranean Sea, poisoning fisheries, and polluting Lebanon’s beaches, all while failing to remedy the garbage crisis.”

ELARD Earth Link and Advanced Resources Development:

Ramez Robert Kayal and his partner Ricardo El Khoury have been registered in the Lebanese Land Registry three times with different capital and registration details. Their file was transferred to Baabda in August 2013. Kayal is also founder and shareholder of Equality Offshore, which was established May 2015. This is the same company that prepared the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the Al-Ghadir project, which was funded by the European Investment Bank and the Islamic Development Bank, yet until today has not been finalized.

Suzy/ Souad Howayek

Suzy Howayek is the project coordinator for the Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project. After being appointed as project coordinator in September 2019, she received $55,000 from the loan allocated for the project in 2020. She had a monthly salary of over $6,000. Suzy is the sister of Marianne Howayek, Lebanese Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh’s assistant since April 2020. Marianne Howayek is the founder of the company CloudX in 2018, through which Howayek contracted (in return for a commission) with FOO in 2020 to launch the “Sayrafa” platform, noting that Howayek used to receive her money exclusively in US dollars even after the Lebanese banks started holding the deposits of the Lebanese accounts.

Dynamesh Company

The company’s owner is Kamal Merhej, who has worked in managing information systems for 11 different projects funded by the World Bank for such organizations as the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), the Ministry of Education and Higher Education, the Ministry of Finance, the Beirut Water Authority, Electricité du Liban, the General Directorate of Land and Maritime Transport in the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, etc.

Dar Al-Handasah, Nazih Taleb and his partners, Matilda Khoury, a member of the Beirut Municipal Council, Marie Nahas, engineer Pierre Abi Akl and others.

This is in addition to companies that work in networks not shown in the World Bank report, such as the Danach company, owned by Mohamed Danach, who is close to Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri and others.

“Local forces are stronger than the supervising World Bank,” said Alawieh. “The loopholes created by the World Bank are exploited under the pretext of professionalism, which the Lebanese authorities have turned to waste.” The approach to loan financing must change within the World Bank itself. The bank must impose strict guidelines and set a black list that prevents dealing with contractors who have a proven record of: delays in implementing projects, political or business affiliations with figures in the authorities.

Current Reality

In May 2021, some forty tons of dead fish washed up on the shore of Lake Qaraoun, which caused great panic among people in the region. There has been a ban on fishing in the lake since 2018.

According to a Daraj investigation by journalist Hussein Mahdi, the Litani River in the early 1990s “provided in the fresh water needs of about one million people, as it irrigated thousands of hectares of agricultural land and constituted a source of income for some 6% of the basin’s population (370,000), working in agriculture, and provided 31% of the income of the agricultural sector that depends on its water.”

Mahdi’s investigation was based on a report issued by the Litani River Authority, which states that “127 municipalities in the upper basin and 19 municipalities in the lower basin are directly and indirectly diverting sewage into the river. In addition, there are 85 factories in the upper basin, 21 slaughterhouses, and 16 farms that dump their waste and divert sewage into the river.”

The Litani has attracted numerous projects and funds over the years. However, they did not succeed in avoiding the catastrophe that rules the river basin today. In 2016, the National Council for Scientific Research declared Lake Qaraoun clinically dead.

“I want to send a message to the donors who are offering aid. I hope they don’t send us anything anymore, because it’s not getting delivered to us, said Ziad Shehab in Bar Elias. “If anything is implemented, it is usually very minimal and does not help at all for the situation to improve… If donor states want to send money for this issue, they should be the ones monitoring the projects, not the Lebanese state, Because we do not have a Lebanese state.”

Read Also: